For years, venture capitalists have been out to change the world. Addressing climate change — perhaps the world’s most vexing issue — just hasn’t been their preferred means of doing so.

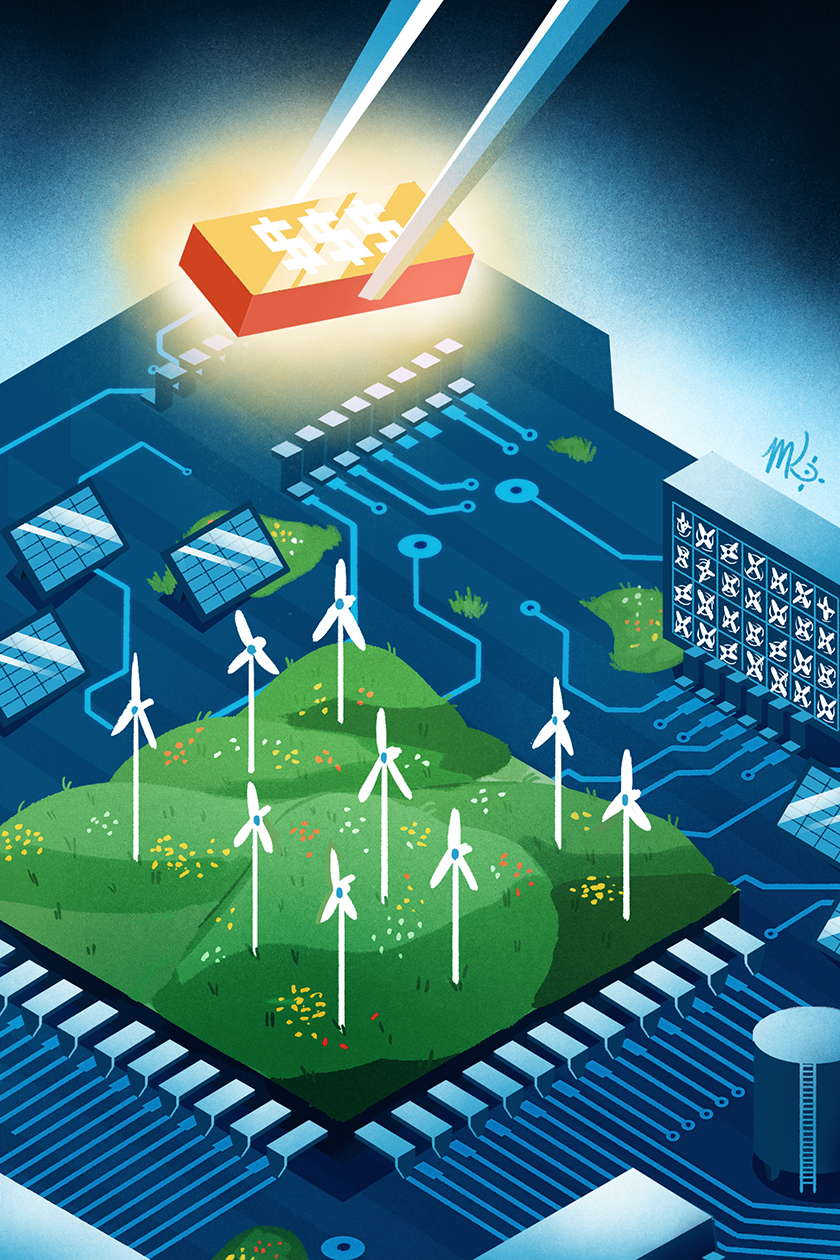

So-called cleantech firms whose products are designed to help the environment in some fashion received less than 3 percent of venture capital funding last year, according to data from PitchBook. But while the high-dollar, high-risk finance vehicle that brought us Facebook, Twitter, and Google has been shirking the climate crisis, environmentally-minded investment firms and companies are picking up more of the slack.

None has made a bigger step than Microsoft. Corporate pledges to reduce carbon emissions are nothing new, but the the Redmond, Washington-based company took a huge step forward last month when it pledged to become carbon-negative by 2030; come 2050, Microsoft says it will have removed as much carbon from the atmosphere as it has emitted since it was founded in 1975. To achieve that goal, and help others do the same, Microsoft established a $1 billion fund to invest in carbon-removal technologies.

“This has been an area that has received very little investment from the federal government, from state governments, or other national governments,” said Giana Amador, co-founder of Carbon180, a nonprofit promoting carbon removal technology. “So the size of investment that Microsoft is making actually is monumental. It’s probably the single largest investment in carbon removal solutions to date.”

Bitterroot relies on the support of its readers.

Consider making a contribution today.

For years, Microsoft and other companies have purchased renewable energy credits to offset their emissions. But the company’s investment fund signals a more tangible step toward crafting new solutions to the climate crisis, one that extends beyond an individual company’s operations.

“Solving our planet’s carbon issues will require technology that does not exist today,” Microsoft President Brad Smith wrote in a blog post announcing the news. “That’s why a significant part of our endeavor involves putting Microsoft’s balance sheet to work to stimulate and accelerate the development of carbon removal technology.”

Scientists are certain that carbon removal is necessary for us to avoid catastrophic climate change; the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change bakes it into the organization’s emission-reduction calculations. The most straightforward way of doing this is scrubbing carbon dioxide from the air or power plant emissions and storing it deep underground, but until there’s a global price on carbon, there’s not much money to be made by doing so. Accordingly, investment in companies doing this work has been slow to build.

That’s the case for other clean technologies, too. A large portion of private funding in this sector comes from purpose-built “impact investment” houses that focus on social or environmental good in addition to financial performance. Microsoft declined to comment further on its investment strategy, but in a sense the company is entering a fray already dominated by its founder. Bill Gates has invested sizable amounts of his personal cash into carbon capture and storage and nuclear energy firms. In addition, he started Breakthrough Energy, an impact fund of $1 billion from the world’s richest people that focuses on cleantech.

So money is flowing to carbon capture, solar firms, and the like — just not from venture capitalists. Not anymore, anyway. After An Inconvenient Truth premiered in 2006, venture capitalists threw $25 billion at cleantech firms over a five-year stretch; come 2011, they’d lost half of it. Reviewing the carnage, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology concluded that firms developing “new materials, hardware, chemicals, or processes” — in other words, stuff instead of software — “were poorly suited for VC investment because they required significant capital, had long development timelines, were uncompetitive in commodity markets, and were unable to attract corporate acquirers.” Silicon Valley’s deepest pockets promptly retreated to apps.

“The venture capital system works very well for the problem that it was designed to solve — creating return for investors,” said Jo Brickman, director of impact strategy at VertueLab, a cleantech investment fund and accelerator based in Portland.

Smaller firms like VertueLab, E8 Angels in Washington, and Elemental Excelerator in Hawaii and California have proven invaluable at shaping early-stage cleantech companies before big-money funds step in. These firms help technology-minded founders establish a business model, and they assist in deploying proof-of-concept demonstration projects.

“If there’s not a partner to that company that’s helping … prove out your technology, the venture capitalists are not going to be able to swallow the risk,” Brickman said.

Elemental Excelerator, which receives funding from Laurene Powell Jobs’ Emerson Collective, has invested $36 million in 99 cleantech firms since 2012. In 2018, it established a portfolio to invest in companies whose products will benefit so-called “frontline” communities in California, the ones that traditionally suffer the worst impacts of pollution and climate change.

“We want to be a bridge between new technology startups and those communities,” said Sara Chandler, who oversees Elemental’s equity and access program. The firm does so with two approaches. One is to change a company’s practices internally. For instance, when Elemental invested in Yerdle, a firm that handles second-hand retail for clothiers like Patagonia and Nordstrom, it helped the company set up a professional development program for its warehouse employees in Brisbane, California. The other method is by bringing portfolio companies’ innovations to poor communities that need them most.

That was the case with Solstice, a Boston-area company that handles customer relationships for community solar — small solar arrays that households can buy into. Stephanie Speirs, Solstice’s founder and CEO, told me that Solstice wasn’t planning to enter California until the regulatory structure changed (state regulations favor rooftop solar installations). Elemental’s investment changed that. “We would not be able to be in California without this funding,” she said. Now, the company is in talks with three Central Valley cities about establishing community solar projects, which could reduce energy costs for low-income folks incapable of installing their own rooftop solar panels because of financial or ownership constraints.

“A lot of funders consider themselves impact investors … but Elemental is one of the funders that’s best about making sure there’s an equity lens to the work,” Speirs said.

These specialized investment houses can lead to more money; Breakthrough Energy has invested in companies from both VertueLab’s and Elemental’s portfolios.

Microsoft’s fund broadens that investment umbrella, but there’s still a long way to go if cleantech investment is to be commensurate with the climate problem.

Amador, of Carbon180, is thrilled that Microsoft has pledged such a large sum toward carbon removal. After all, she said, carbon removal investment is so nascent that even “really small amounts of money can have huge results” — let alone $1 billion.

But as we grapple with the scale of climate change, she said money — from investors, companies, and governments alike — needs to find its way to a diverse array of climate solutions. “We need as many tools in our toolkit as possible.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story said Elemental Excelerator was part of the Emerson Collective; in fact, it is a separate entity that receives funding from Emerson. We regret the error.