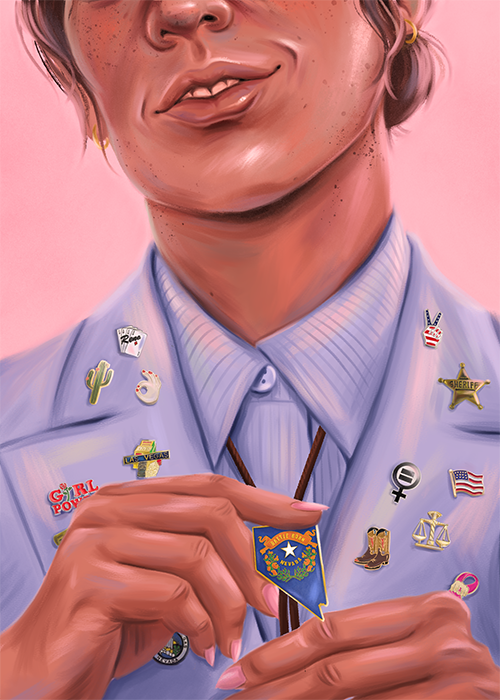

Upon entering the four-story Nevada Legislative Building in Carson City, visitors are surrounded by framed photos of lawmakers dating back to Nevada’s 1864 statehood. Most of those frames hold photos of white men, sporting various styles of facial hair reminiscent of their eras.

But the top floor offered a different scene when I visited in April.

There, almost all of the offices were occupied by female senators and Assembly members. Female staff wielded smartphones and laptops to manage the legislators’ crowded calendars. Women lobbyists swarmed the halls, vying for support. Outside of the main hearing room, girls wearing cowboy hats waited for the chance to speak with lawmakers about horses.

Nevada’s 2019 Legislature was the first in United States history with a female majority. After 155 years of men in power, this female-dominated body had 120 days to address a challenging question: Do women actually legislate different than men?

There appeared to be at least one clean case study. During the 2019 session, several Southern states with male-majority legislatures passed laws that banned or criminalized most abortions. Conversely, Nevada’s majority-women Legislature passed the Trust Nevada Women Act, which decriminalized self-induced abortions and those induced by medication without the advice of a doctor. The measure also changed informed consent requirements.

“These are draconian laws that have no business in a free society,” Assemblywoman Shea Backus, a Las Vegas Democrat, said on the Assembly floor before a May vote on the bill.

State Senator Ira Hansen, a Republican who received the Pro-Life League of Nevada’s Champion of Life Award in 2016, opposed the bill. He finished one statement on the Senate floor by telling his colleagues that he had four daughters, four sisters and nine granddaughters. “So, I kind of resent that this is a man-versus-woman kind of issue,” he said.

It’s easy to look at the dichotomy of abortion policies between Nevada and Southern states as just that: a man-versus-woman issue. But the relationship between gender and lawmaking is far more complex. The Nevada bill that lifted abortion restrictions passed with the support of three-quarters of the 33 assemblywomen and female senators. Of the eight women who voted against it, six were Republicans.

“I want to make the record perfectly clear: I do not support criminal penalties for women who have abortions,” Republican Jill Tolles of Reno told her Assembly colleagues. But Tolles voted against the bill, in part, because it removed a requirement that doctors verify the age of a woman seeking to terminate a pregnancy.

“There’s this expression: all hat, no cattle. You can look like a cowboy, but if you can’t do the work, then you’re not worth your salt. In the West, if you can do the work, then people will let you do the job.”

Assemblywoman Robin Titus, a doctor in conservative Lyon County, took issue with the same provision. “I do trust women,” she said. “Who I don’t trust is those who would take advantage of women and children.”

Even female lawmakers weren’t certain that the majority-women class of lawmakers was the reason the bill passed. Senator Yvanna Cancela, the state’s first Latina senator and sponsor of the measure, attributed the bill’s passage to a variety of factors, including the fact that Democrats simultaneously held the Senate, Assembly, and governorship for the first time since 1992.

“The Trust Nevada Women Act is interesting both because it happened in a majority-female Legislature, but also because it is the next story point in Nevada’s long history of being a pro-choice state,” she said. “We can’t ignore that there was a Democratic majority in both the Legislature and in the governor’s mansion when talking about policies that got passed [that] were progressive in nature, and certainly many had a women-centered lens.”

Legislation can be influenced by gender, yes, but also by race, religion, geography, party, and other factors. There is no blind study that can directly determine how stronger female representation at the state level affects policy, no alternate universe where scientists can run scenarios testing gender against party, race, or geography.

But there is the West.

“Western states have traditionally had higher percentages of women in office,” said Katie Ziegler, who runs the National Conference of State Legislatures’ Women’s Legislative Network, a professional development network that is available to every female state legislator in the country. Ever since Coloradans Clara Cressingham, Carrie Holly and Frances Klock became the first women elected to a state legislature in 1894, the West has had a strong tradition of female representation, Ziegler said.

Women didn’t win just in Nevada in the 2018 election. Last year, more women were elected to Western state legislatures than ever before, according to data from the National Conference of State Legislatures. Four of the top five states for female representation are in the West. In addition to Nevada’s 51 percent women legislature, Colorado comes in at 47 percent, Oregon at 41 percent, and Arizona at 39 percent. Every Western statehouse except Arizona and Idaho added women after the 2018 election.

“This last election, you saw a huge jump in the number of female candidates running, which translated to a big jump in the number of women who won,” Ziegler said.

Western state numbers differ from those at the national level, where women make up less than a quarter of Congress. The U.S. ranks 76th globally — tied with Afghanistan — for women’s representation in government, according to the International Organization Of Parliaments. If Nevada were an independent country, its share of women lawmakers would rank fourth in the world, after Rwanda, Cuba, and Bolivia and just ahead of Mexico and Sweden.

“I think that gun control may not have even been introduced by a man. The abortion bill wouldn’t even really have gotten consideration a few sessions ago.”

“I’ve always attributed [the early representation of women in Western statehouses] to the rugged individualism of the West,” said Patricia Dillon Cafferata, who served in the Nevada Assembly in 1978 and then became the state’s first woman treasurer in 1982. Her mother, Barbara Vucanovich, was Nevada’s first U.S. congresswoman in 1983 and served in the role until 1997.

“There’s this expression: all hat, no cattle,” Cafferata said. “You can look like a cowboy, but if you can’t do the work, then you’re not worth your salt. In the West, if you can do the work, then people will let you do the job.”

Others attribute Nevada’s high share of female lawmakers to the relative openness of the state’s political parties and process.

“We don’t have the party bosses like an eastern or a Midwestern state has, where everything’s very established,” said Helen Foley, who was the youngest woman ever elected to the Nevada Senate in 1982. Foley now works as a lobbyist for a firm she founded with two other women.

“It’s a very welcoming state, and the party structure hasn’t been so strident or dogmatic that you can only run if they say you can run,” Foley said. “It’s far more independent than that.”

Cancela, the sponsor of Nevada’s abortion rights bill, said that while she wasn’t sure whether the passage of such bills could be attributed solely to the women majority, she did notice a broad range of legislation that affected women passed during the 2019 session.

“Whether it was about sexual violence, or domestic violence, or about women’s pay equity, or paid time off, there were a number of bills that I think came from a woman’s perspective,” Cancela said.

Steve Sisolak, Nevada’s Democratic governor, signed more than 600 bills this session. Lawmakers passed a “red flag” law that facilitates the seizure of guns from people deemed a threat to themselves or others, and another measure that required background checks for most private gun sales. The Legislature reformed sentencing in an attempt to reduce the state’s incarcerated population, and boosted education spending by $300 per pupil. In addition to abortion decriminalization, lawmakers also created laws to protect Nevadans from unexpected medical bills and to prevent insurers from denying coverage due to preexisting conditions. Sisolak signed a bill that makes it a felony to advance prostitution outside legal brothels. Lawmakers also passed a minimum wage increase, strengthened collective bargaining for state employees, guaranteed paid sick leave for workers, and shored up equal-pay protection based on gender.

These bills may have passed because of the Democratic trifecta, but there is some evidence that female lawmakers are more likely to introduce bills on issues that disproportionately affect women — think childcare, pay equity, and reproductive rights — than their male counterparts, said Kelly Dittmar, an assistant professor at Rutgers University’s Center for American Women and Politics.

“Even though women on different sides of the aisle hold very different positions on them, they’re still more likely to bring them to the table and sponsor the bill,” Dittmar said.

For another example, look to Colorado. There, lawmakers passed a similar slate of bills in 2019 that addressed gun control, criminal justice reform, and health care expenses. Education funding was boosted, and lawmakers ratcheted up enforcement of gender-based nondiscrimination laws.

While the science on how women legislate at the state level is thin, research shows that women in Congress feel a need to be a voice for the voiceless.

“Generally, you find that women vote along party lines — like men.”

“The women themselves said to us repeatedly, ‘We have an understanding of what it’s like to not be reflected in these conversations,’” Dittmar said. “So, they take that on as an additional responsibility to not only represent their constituency geographically, but also represent those more broadly who don’t have a voice in the system.”

For Tolles, the Republican assemblywoman, personal experience trumps gender when it comes to lawmaking.

“We all bring our experience, our history, our stories, and our understanding to the discussion and our decision making,” Tolles said. “More diverse voices at the table allow for more representation when we’re making decisions about any kind of issue.”

Cancela made a similar assessment. “Because we had a majority-female Legislature that was diverse in class, ethnicity, background, and age, I think there were perspectives and questions that were brought up that may not have risen to the forefront otherwise,” she said. “It definitely affected the way that we made policy this session.”

Foley, who has been involved with the Nevada Legislature for more than three decades as a staff member, assemblywoman, senator, and now lobbyist, noticed a difference in the bills that were introduced this session.

“I think that gun control may not have even been introduced by a man,” Foley said of the red flag bill sponsored by Las Vegas Assemblywoman Sandra Jauregui. “The abortion bill wouldn’t even really have gotten consideration a few sessions ago.”

But Titus, who first took office in 2014 and is the Assembly Republican caucus leader for the 2020 election cycle, disagreed. “I have three, four bills [awaiting the governor’s signature],” she said when we spoke in April, “and I would say none of them had anything to do with the fact that we [have a majority-women Legislature] this year.”

In 1989, Dana Bennett was the only woman in the Nevada Legislature’s research division. There, she became fascinated by the women in the statehouse, and went on to write her doctoral thesis on women legislators and tax policy development in Nevada before 1960. During her research, Bennett found that these women didn’t primarily identify with their gender.

“Their first identity was their community,” Bennet said. “Reporters would ask a woman, ‘What’s the legislation you’re going to be most interested in?’ And they would say, ‘What’s good for Nevada.’ That was really their focus.”

Today, Bennett is president of the Nevada Mining Association, the first woman to hold the position. When we spoke, she brought up a rallying cry from the women’s movement of the 1960s: Biology is not destiny. “I keep thinking about this female majority and observers who are assuming that biology is destiny,” she said. “While we as American women and Nevada women are socialized in certain ways, there’s no guarantee that we’re going to walk in one step.”

“When there are only two women, and men can go in the bathroom to talk policy, that’s a place we can’t go. Well, now we can go to the bathroom.”

Sue Wagner, a former state legislator and the first woman to be Nevada’s lieutenant governor, was one lawmaker for whom philosophy mattered more than party. She voted for a law guaranteeing abortion rights in 1973 and tried to pass a statewide Equal Rights Amendment in 1981.

“I was the Republican that supported those, and if anybody else did, it was a Democratic woman,” Wagner said.

But Wagner may be an exceptional case.

“We know that ultimately, generally, you find that women vote along party lines — like men,” Dittmar said.

Which begs the question: if women tend to vote along party lines, just as men tend to do, does gender parity in politics matter at all? Cancela said there was pressure for the female-majority Legislature to prove that this newfound parity mattered.

“I don’t think that’s a fair pressure, but I think it’s a part of the painful tension that we as a society have to undergo to get to a place where equality is the norm,” Cancela said. “Where it’s not a big deal that there are more women than men in office because that’s something that happens across the country regularly.”

Regardless of how women legislate, their representation impacts the workings of the statehouse.

“I ran into a senator the other day, and I said, ‘Hey, we can do business in the bathroom,’” Bennett said. “She looked at me sort of funny. But when there are only two women, and men can go in the bathroom to talk policy, that’s a place we can’t go. Well, now we can go to the bathroom.”

Today’s lawmakers know they follow women who had to work in far less equal environments.

“I’m very, very aware that there are generations of women who came before us, who worked on so many of these issues long before we ever entered the building,” Tolles said. “They paved the road for so many decades before, and we’re continuing that work.”

The large number of women lawmakers in the 2019 session could pave the road for future generations, too. In 2018, Nevada held an art contest among students, the winner of which would lead the Pledge of Allegiance when Sisolak was sworn into office. Contestants submitted artwork based on the theme “Home Means Nevada,” the state song.

Sydney Larsen, a fourth-grade student at Seeliger Elementary in Carson City, was one of two winners. She drew an American flag, a bright blue sky, and the words, “Nevada means home to me because they have more women in the NV Legislature. As a girl, I can lead the Legislature one day.”

“That’s so powerful,” Cancela said. “So, yes, it’s hard to measure, and it’ll be a long time before there is any real data on what a difference having more women in office makes on young women of today. But, it’s undeniable that it’s powerful and noticeable.”