As dusk fell on a gathering in Oakland on June 7, the multicolor LED lights emanating from the base of a new sculpture became more vivid. Shifting from pink to blue to yellow, they cast an intricate pattern of geometric shadows around a laser-cut metal vase holding lamp posts resembling 10-foot poppies. Children zoomed around the structures, their parents chatting with young professionals dressed in the ubiquitous business-casual attire of Silicon Valley.

Nearby, behind an empty microphone stand, a man in striped bell bottoms, a top hat, and shirtless except for a vest inspected a miniature model of the floral sculpture. Another man, in a floor-length fur-and-sequin coat, was filling a friend’s Dixie cup with wine. Others in the group sported nose rings, brightly colored hair, dreadlocks, unkempt beards, and patterned harem pants.

One of them was Serge Beaulieu, a local artist who created the sculpture. Beauliu and his partner, Yelena Filipchuk, are known for the Hyperspace Bypass Construction Zone, or HYBYCOZO, a series of big, geometric sculptures that regularly appear at the annual Burning Man festival in Nevada’s Black Rock desert. Beaulieu was here with the after-work crowd because the poppies, coupled with a similar metal oak across the plaza, are the first permanent public HYBYCOZO installation. When Beaulieu approached the microphone for a short speech, he snuck in some kudos for his typical desert venue.

“Thank you to the Burning Man Project,” Beaulieu said. “I don’t think any of this would have been possible without them letting us practice and experiment for years.”

Beaulieu’s Oakland installations represent a shift in the public art scene. In cities across the West, public art agencies are turning to the festival circuit to find a new breed of civic art. Oakland, Los Angeles, Reno, and San Francisco have all bought installations in recent years from artists who made their names at Coachella, Burning Man, Lightning in a Bottle, and other festivals. As a result, artists are cultivating new venues while loosening up public art’s conservative reputation.

“Younger people want more out of their art than their parents,” said Charles Gadeken, a San Francisco artist whose work has appeared at Coachella and Burning Man. “They aren’t interested in just a little bronze sculpture of a child fishing. The cities have to reach a little further to reach their current audience.”

The San Francisco-based organization behind Burning Man spent $1.3 million on 383 installations in 2018. Taking a cue from Burning Man, other, more commercialized festivals have ramped up their investments in art. The Coachella music festival, for instance, paid Gadeken around $200,000, he said, to bring a 50-foot tower of geometric light boxes to its 2014 event. Santa Fe artist Don Kennell said Coachella purchased Yard Dog, a large dog sculpture made from corrugated sheet metal, for $27,000 in 2011.

Many of the pieces these festivals commission end up in the surrounding communities. As festival art has become more refined, the broader art community has come to respect what used to be one-off installations.

“There’s a very different attitude toward Burning Man,” said Laura Kimpton, a San Francisco artist who has long displayed art at the festival. “Fifteen years ago, Burning Man probably was a rave. … Now it’s 100 percent an art event. It’s a gallery, a 6-mile by 6-mile art installation.”

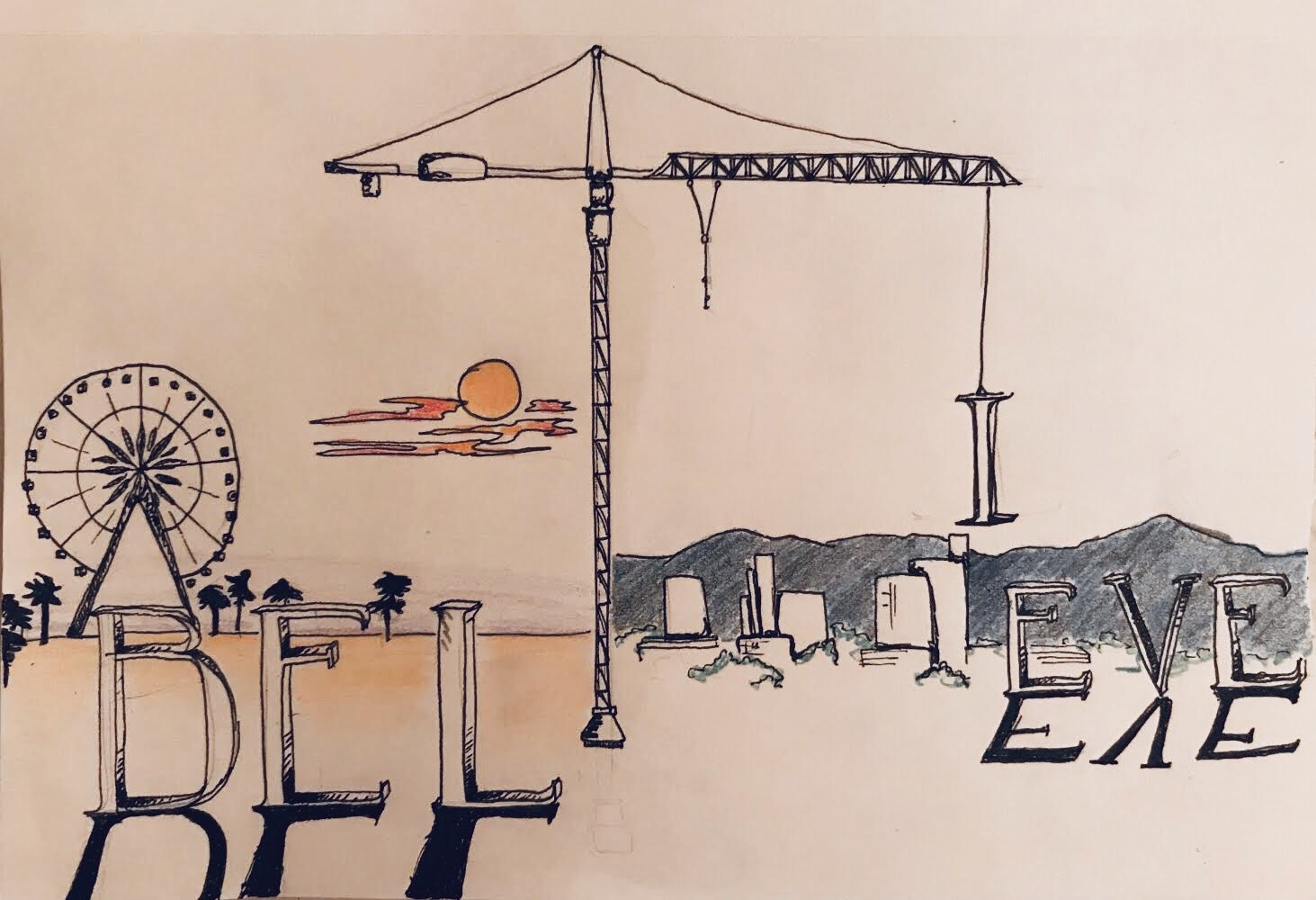

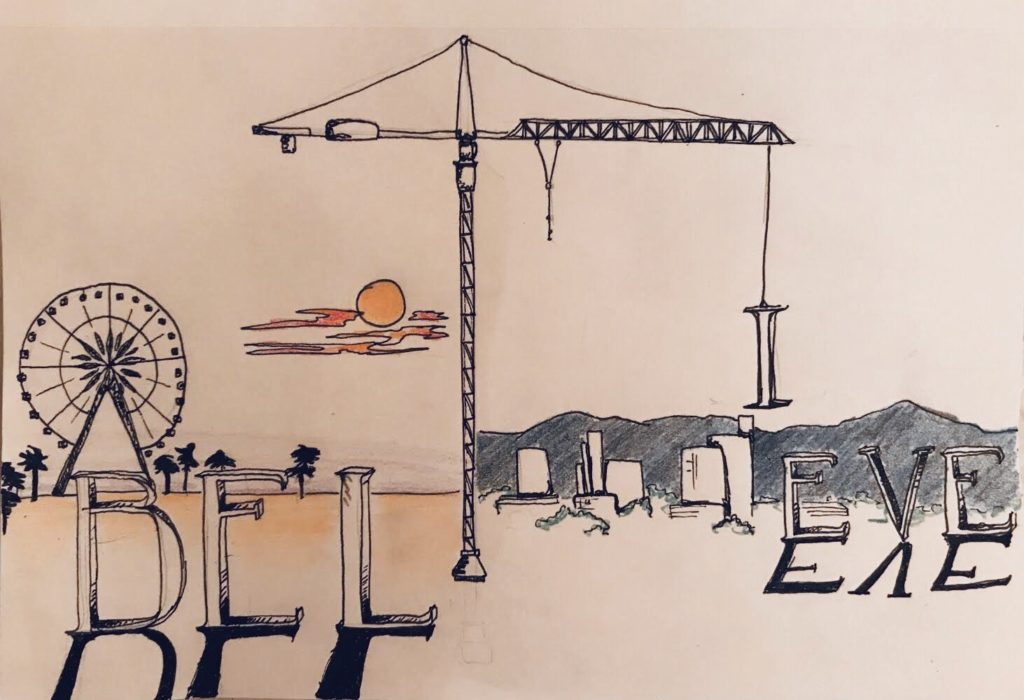

The Reno Arts and Culture Commission in 2016 spent $70,000 on a Kimpton installation spelling out ‘Believe’ after it appeared in Burning Man in 2013. The sculpture sits in the city plaza, where it has become a favorite spot for tourist photos and is now the de facto slogan of the city.

“We like to have Burning Man pieces because we are the gateway to Burning Man,” Nettie Oliverio, chair of the commission, said. “Most of us regularly go out to the playa to see the art. We keep in our heads what potentially could be good. And the mayor really liked [Believe] becoming the mantra for the city of Reno.”

Some worry Reno has become too reliant on Burning Man, though. “I’m burnt out on the lack of diversity,” Matthew McIver, another member of the commission, said. “I feel like we need to open our horizons to other artists.”

The art these festivals commission tends to move around. Take Kennell’s work: A 35-foot polar bear clad in car hoods was initially commissioned for Burning Man and later stood in front of the Ferry Building in San Francisco during the Global Climate Action Summit in 2018. Two Coachella sculptures, one a ram and the other a roadrunner, ended up in Los Angeles-area traffic circles. Gadeken’s light-box tree, called Squared, went from Coachella to Burning Man to, most recently, a San Francisco park, where it sat for a year. Next up is a two-year stint in Reno.

“Building something at Coachella or Lightning in a Bottle is a highly regulated environment with a lot of things to worry about besides just making it look cool,” said Jesse Shannon, chief marketing officer of DoLab, which produces the Lightning in a Bottle festival. “As the festival business has matured, the community is better equipped to work with governments to offer this type of creativity and inspiration to a city environment.”

Festival art can drive tourism and boost a city’s social media presence. Plus, the popularity of festivals has made it clear to cities that their residents value large-scale art. But city officials often look for modifications to the art before it’s considered suitable for public installation.

“We don’t want people climbing all over stuff in a city where there is liability,” Oliviero, with Reno’s arts commission, said. “We don’t want sharp pointed objects. We don’t want things falling apart on us. For public art in a city, there are all kinds of concerns when we decide whether a piece is going to be good for an urban environment.”

For now, festival art and public art seem to be good bedfellows. Festivals give the artists a chance to try something new before they pitch the idea to cities and work through the red tape. Meanwhile, the embrace of cities signals that festival art is entering the mainstream. Earlier this year, the Smithsonian Institution hosted an exhibition of Burning Man art. And the interest is driving demand for artists used to making one-off projects for eccentric gatherings in the middle of nowhere.

“Artists are getting opportunities to make art they never would have been able to before,” said Kimpton.