For many Albuquerque residents, an evening on the porch means colorful skies and watching the nearby Sandia Mountains transform to a shade of peachy pink as the sun sets. Esther Abeyta has a different view from her home in the San Jose neighborhood: train tracks, about a dozen sets, just outside her backyard. Trains steadily rumble by — horns blaring, diesel engines emitting exhaust. Their bulk shakes her home. The simple pleasure of enjoying an evening outside? Nearly impossible.

“It hurts,” Abeyta said. “I’d love for us to be able to sit outside and see the beautiful sunsets and hear the birds.”

When I visited Abeyta on a sunny February afternoon, a neighbor, a middle-aged man in a baseball cap, was mending the fence that separates the community from the tracks. Turns out local kids had cut through the barrier to tag the trains that sit there overnight. They also left their garbage in the empty lot next to Abeyta’s home.

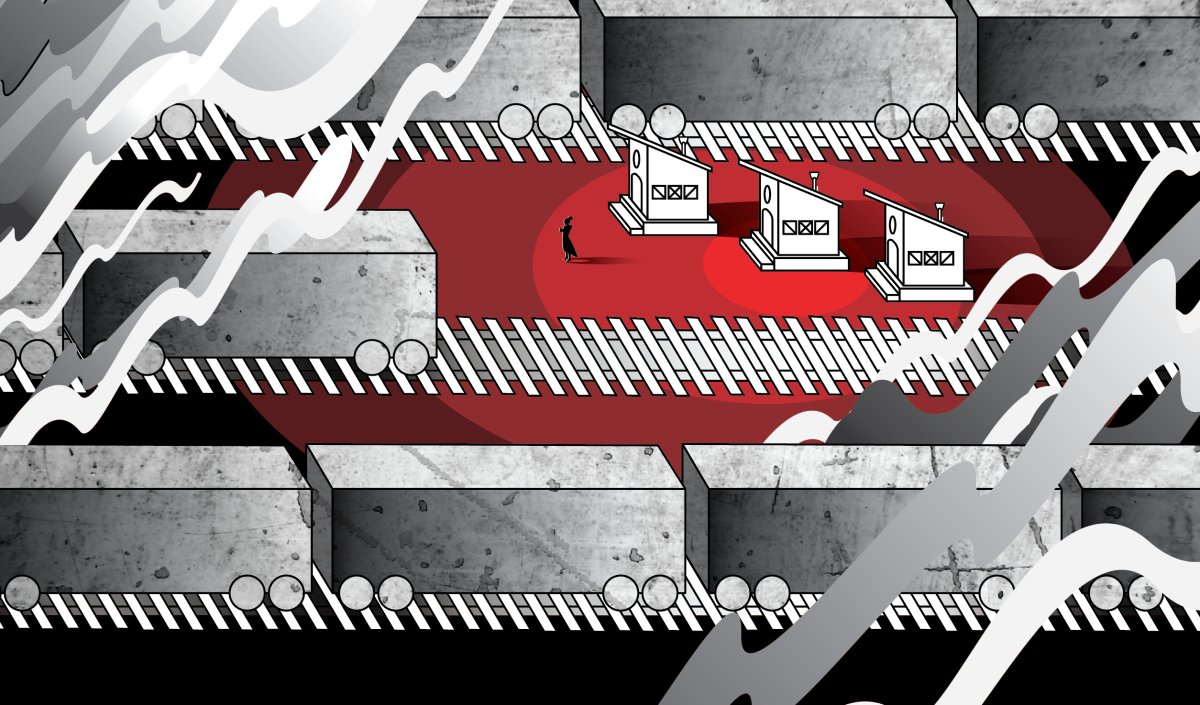

Trains aren’t San Jose’s only nuisance. For years, this neighborhood has been steadily inundated with pollution from a variety of sources: rail yards, asphalt companies, bulk plants that store gasoline and diesel fuel. The 2.5 square-mile neighborhood has two federally designated Superfund sites — areas that are so polluted with hazardous waste that the federal government is compelled to orchestrate long-term cleanups and monitoring.

Abeyta, 56, grew up here. For the past decade, she and her husband, Steven, have fought to clean up their community and to keep new polluters from setting up shop. In that time, Abeyta has become fluent in environmental laws and policy. She spends much of her time reading technical documents, writing emails to government officials, and attending meetings — that is, when she’s not spending time with family or helping out at the local Catholic church. She and Steven balance all of this with work; he’s in telemarketing, and she’s in retail. But San Jose provides a case study showing that even with a diligent advocate like Abeyta on its side, the deck is stacked against places like this, where residents have traditionally lacked the resources to fight back.

Across the West, communities of color — four in five San Jose residents are Hispanic — suffer disproportionately from the output of polluting industries, and are more likely to live near Superfund sites and other places detrimental to their health. Without the resources to hire lawyers, lobby officials, or attend hearings en masse, these neighborhoods rely on passionate community members like Abeyta to speak on their behalf.

It’s a daunting task for an individual to shoulder. Abeyta has had her share of victories, but at times is exasperated by the seeming onslaught of battles she must wage simply for clean air and water. “We’re an environmental justice community,” she said, “but there’s no justice for us.”

San Jose, situated on the fertile east bank of the Rio Grande, was a farming community in Albuquerque’s early days. The railroad’s arrival in the 1880s kicked off an industrial transition that accelerated after World War II. In 1948, Eidal started welding operations in the neighborhood; before long, American Car and Foundry, General Electric, Chevron, ATA Pipeline, and Texaco moved in.

Abeyta attended East San Jose Elementary School in the late 1960s and early ’70s. She recounts playing outside as a child and feeling a sense of community. “You knew your neighbor,” she said. Those childhood memories, though, have been tainted by what she knows now. She remembers watching a tank truck drive by, spraying liquid on the ground — a common method for settling dirt in this high desert community, especially during the volatile spring winds. Abeyta thought the trucks were spraying water, but, years later, as she researched polluters in her community, she came upon a document detailing how a company that operated in the neighborhood at the time had sprayed combinations of waste oils and solvents as a means of dust control.

“Growing up, I never knew why people in my neighborhood — my friends’ mothers and their aunts — were dying of cancer … Later on, when I got involved in all of this, it all made sense.”

In 1979, a number of hazardous contaminants like tetrachloroethane and dichloroethene were discovered by the Environmental Protection Agency in a San Jose well near a General Electric Aviation manufacturing site, but it would be another 10 years before the agency would require GE to treat San Jose’s contaminated drinking water at what was designated the South Valley Superfund Site. Five years later, in 1994, the New Mexico Environmental Department forced Chevron, ATA Pipeline, and Texaco to treat contaminated water and soil in another South Valley section. In that section, dubbed the Univar site, 850 million gallons of groundwater were extracted and treated until 2006; treatment is ongoing at the GEA site. Groundwater treatment continues, too, at the nearby 89-acre AT&SF Superfund Site, where a wood treatment plant operated for 64 years, leaching creosote and oil mixtures all the while.

San Jose is tucked away in the city’s South Valley, where more than 80 percent of residents identify as Hispanic, and nearly 27 percent of the community lives below the federal poverty level — twice the national average — according to census figures. According to a 2015 report from the National Collaborative for Health Equity, life expectancy in the South Broadway area of Albuquerque, where San Jose is located, is between 66 and 70 years. More affluent areas of the city enjoy life expectancies of 85 to 94 years.

According to a 2011 Health Impact Assessment by the Bernalillo County Place Matters Team, Hispanic people living in San Jose have significantly higher death rates than those in other parts of the county for 10 of 11 leading causes of death, including heart disease and cancer. A litany of research has found correlations between environmental burdens, stress, and premature deaths in communities like San Jose.

“Growing up, I never knew why people in my neighborhood — my friends’ mothers and their aunts — were dying of cancer,” Abeyta said. “Later on, when I got involved in all of this, it all made sense. And then I started looking at the people in my neighborhood saying, ‘Wow, I know a lot of these people that have these health issues.’ And it’s because of where we live. Because of the industry.”

Across New Mexico, contaminants from mining, oil and gas development, and heavy industry disproportionately affect communities of color. Part of this is because the state is diverse; 50 percent of New Mexicans identify as Latinx or Hispanic, and 11 percent are Native American. But, according to Juan Reynosa, deputy director of the environmental nonprofit SouthWest Organizing Project, industry tends to “concentrate in areas that have been suppressed for years.”

Eric Jantz, a staff attorney with the New Mexico Environmental Law Center who has represented San Jose residents in legal disputes, agrees, adding that these communities are also “disproportionately denied the benefits of the industries that are doing the pollution.”

Class and race have long been at play when it comes to the positioning of polluting industries, and it has to do, Dillon said, with “some people’s bodies being [treated as] more important than others.”

Numerous studies have found that people of color nationwide are more likely to be exposed to dangerous pollution. Proximity to Superfund sites is one such measure. According to the EPA, 21 percent of nonwhite Americans — including 19 percent of black people and 23 percent of Hispanics — live within three miles of a Superfund remedial site.

“It’s not just about Albuquerque, and it’s not just Latino communities,” said Lindsey Dillon, a sociologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who specializes in environmental justice. Class and race have long been at play when it comes to the positioning of polluting industries, and it has to do, Dillon said, with “some people’s bodies being [treated as] more important than others.”

Examples abound. El Paso, a border city that is about 80 percent Hispanic, has repeatedly appeared on the American Lung Association’s list of most polluted cities in the United States. El Paso County households earn 25 percent less than the state median income. And studies show the city’s nonwhite populations are disproportionately harmed by pollution from the area’s trans-border truck traffic, airport, and Fort Bliss Army base.

In Seattle, residents of the city’s South Park, Georgetown, and Beacon Hill neighborhoods along the Duwamish River suffer illnesses such as asthma, diabetes, and colorectal cancer at a higher rate than anywhere else in King County. These communities have prominent racial minority populations, a significant number of whom are refugees. The Lower Duwamish Waterway Superfund Site was established in 2001. The river remains an important fishing site for local tribes and immigrants from fishing communities, though fish and shellfish caught there often contain toxic levels of contaminants.

People of color similarly bear the brunt of Silicon Valley’s largesse. In 1998, the American Sociological Association found that toxic emissions in that region are concentrated in neighborhoods that tend to be poorer and with higher concentrations of Latinx people. Such is the case in the San Miguel neighborhood of Sunnyvale, which has high concentrations of Latinx, Asian American, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander people. There, groundwater is contaminated by a solvent that was used to make computer chips, and is known to cause cancer and birth defects. The community is home to three Superfund sites.

Many of these polluting industries establish themselves in pre-existing communities of color, not the other way around. A 2015 study in Environmental Research Letters found that “rather than hazardous waste treatment, storage, and disposal facilities ‘attracting’ people of color, neighborhoods with already disproportionate and growing concentrations of people of color appear to ‘attract’ new facility siting.”

Economics is complicating that picture, Dillon says. For example, recent immigrants from Central America may move into polluted areas in expensive cities like Los Angeles because housing there is more affordable.

Abeyta’s activism began in 2011, when a company called New Mexico Recycling and Transfer wanted to build a transfer station and sorting facility in San Jose. At the time, she had zero knowledge about things like zoning or how to push back within the environmental review process.

“We felt helpless, really,” Steven, her husband, said. They believed that such a facility would just add to the pollution already in the area, increase heavy truck traffic, and bring in new health risks associated with all the waste that would be brought in. The Abeytas felt vulnerable. “We didn’t know what we could do.”

But with some research and help from activists in a nearby neighborhood, Esther and Steven fought back. They convinced county commissioners to halt the facility’s permit approval until a health impact assessment could be completed. The company’s request for a special-use permit ultimately was denied.

Over the years, Abeyta has versed herself in the technicalities of environmental laws and regulations; she’s something of a zoning expert now. She speaks the vernacular: anything from Title VI complaints to environmental assessments is in her wheelhouse. Abeyta dons a small tattoo displaying the letters “EA” on her forearm; they’re her initials, but I jokingly asked her if they stood for “environmental assessment.”

Her regulatory fluency is critical. In San Jose, she says, there is a general hesitation within the community to speak out. Some residents may work for the city or county and fear retribution from their bosses. Others are undocumented immigrants and don’t want to draw attention to themselves. “People feel intimidated,” she said. “A lot of people feel reluctant for different reasons.”

“We’ve been here. We know all the neighbors. I care for the community, and I hope there’s something we can do.”

Olivia Greathouse, another San Jose resident, shares Abeyta’s concerns for the neighborhood. Her family has lived in San Jose since the 1950s. “We’ve seen all sorts of stuff happen,” she said. “They continue to keep putting these companies here. We’re really tired of it.”

Greathouse is particularly frustrated with the odor from one of the area’s asphalt plants. About two years ago, it bothered her so much that one day she held her breath to escape it. The same day, she had a heart attack. She jokes that she may have caused it herself from holding her breath.

Greathouse’s father left San Jose in the 1970s for another area of Albuquerque, and outlived her mother by nearly 20 years. Greathouse can’t help but wonder if it’s because he left the neighborhood. “If that’s what it is, I need to get out of here,” she said, laughing. But, at the same time, she doesn’t want to leave. “We’ve been here. We know all the neighbors. I care for the community, and I hope there’s something we can do.”

“Esther and her husband, God bless them,” she added, “because they have educated themselves a lot and have come a long way.”

Abeyta regrets letting her daughter sleep with the windows open when she was young. When the family moved back to Albuquerque in 1999 after living for a time in Colorado Springs, her then-teenage daughter developed asthma within a year. Many of the passing trains idle in the neighborhood all night, emitting exhaust fumes that Abeyta worries made their way into her daughter’s bedroom.

Today, air quality is Abeyta’s primary concern, and the latest threat is the proposed Sunport Boulevard Extension. The project would expand a nearby road leading to the Albuquerque International Sunport — the airport just east of San Jose — into a four-lane divided highway for about a half-mile past its current terminus.

Community members have successfully delayed this project since it was first proposed in 2011. In that time, three environmental impact assessments have been released by Bernalillo County Public Works, the latest in July 2018. The report acknowledged a number of pre-existing air quality concerns in the community, but concluded that carbon monoxide levels would remain “well below” the U.S. National Ambient Air Quality Standards. But according to a 2015 assessment by Human Impact Partners, the proposed extension would create traffic congestion and exacerbate air quality issues in a neighborhood that already “has among the highest death rates in the county from several health conditions.”

In late 2018, Abeyta learned that the EPA had proposed delisting a portion of the South Valley Superfund Site — the same portion of the site that the proposed Sunport extension would cross. She wondered whether the two were connected, so she and Steven emailed an EPA representative out of concern. In December 2018, EPA officials met with local politicians and community members. According to Abeyta, at that meeting, state Senator Michael Padilla asked the EPA and New Mexico Environmental Department to wait a year before making any decision to delist so incoming state legislators could learn about the site, review information, and comment. They are awaiting response; the local EPA office did not respond to a request for an interview.

The fight over the Sunport Boulevard expansion has revealed a new ally, though, and potentially an important one. Last year, Albuquerque Mayor Tim Keller withdrew the office’s support for the project, which the previous administration had backed. Abeyta and Jantz, with the New Mexico Environmental Law Center, cited the move as one sign that the Democratic mayor is taking San Jose’s issues seriously.

“The San Jose community in Albuquerque has had more than its share of environmental and social burdens, and this administration recognizes and honors that history,” Keller’s office said in a prepared statement. “Mayor Keller initiated a reset in the City’s relationship with the community, shifting the culture through transparency and engagement.”

“At this point we’re cautiously optimistic,” said Jantz. While some unease remains, especially concerning air-quality permitting, “the Keller administration has been very responsive to our concerns. This is a kind of change we’ve never seen before in any administration, Republican or Democrat.”

Perhaps the most notable turn of events for San Jose was a March vote by the Albuquerque Air Quality Board to grant the community an alternative dispute resolution. Four years ago, San Jose, SWOP, and the New Mexico Environmental Law Center filed a Title VI Civil Rights complaint against city and county air-quality regulators. The resolution means that, in the future, these agencies will collaborate with San Jose representatives to negotiate mutually acceptable settlements for all air permitting.

“Other communities have seen good results with this program,” Jantz said. “Ideally, negotiations would result in systemic reforms that would affect all permitting actions, not just a particular operation.”

Abeyta expressed her enthusiasm for this unexpected turn of events in a group email to fellow activists and supporters following the decision. “It is through your years of encouragement and support,” she wrote, “we are here today grateful and thankful for the blessing we received.”

Abeyta is eager to get the process going, though she knows her work is not yet over. Finally, though, her community will be a part of the decision making process, not just affected by it, a feat that’s been elusive for decades.

“This is a once in a lifetime opportunity for us to get to sit down and have this discussion,” she said.