Jackie Fleming first witnessed the magnitude of wild-horse holding pens when she visited Pauls Valley, Oklahoma, in 2010. “They had about 600 horses … all the pens filled with horses. I couldn’t believe it,” she said. Those horses were rounded up — as they still are — by the Bureau of Land Management from states throughout the West to maintain appropriate wild horse populations. The practice, along with fertility treatment, is the BLM’s main strategy for keeping horse numbers at a level that won’t damage the ecosystems they inhabit. The BLM estimates Western rangeland can support only one-third of the current 82,000-strong horse population, but the agency’s strategy has long been controversial. Horse advocates argue that livestock grazing on BLM land have a much greater impact than free-ranging horses. In 2017, the BLM authorized grazing for the equivalent of 677,000 cow-calf pairs.

After visiting Pauls Valley, Fleming decided to begin adopting from the BLM. “It was like the floodgates opened up after I saw those pens,” she said. “I came home, and I was like, ‘I have to go back and get a few more.’”

Fleming’s ranch in northeastern New Mexico is home to 41 horses, but that’s a drop in the bucket: BLM is still holding more than 50,000.

This horse, named Redbo, sports a BLM brand on his neck. The BLM shows horses at three adoption events, after which the horses are branded on the rear and considered eligible for sale. Redbo was rounded up in Nevada, and Fleming adopted him from Pauls Valley nine years ago.

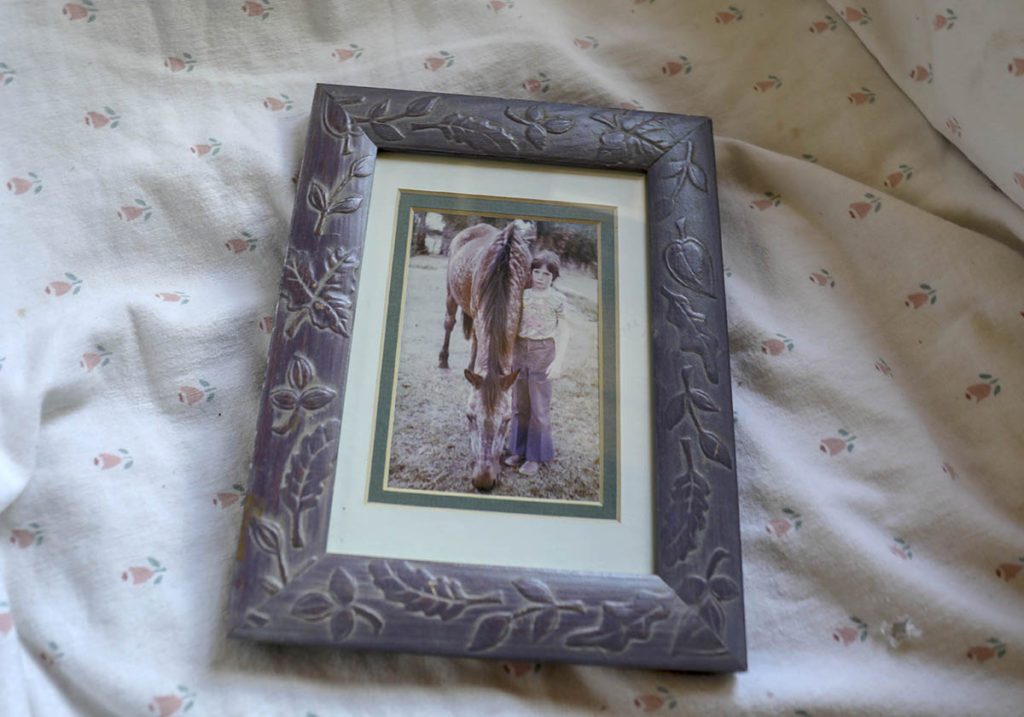

Fleming, pictured here as an 8-year-old in Kenya, was born in Hong Kong. She traveled around the world as a girl, but the American West always stuck with Fleming. Books, including My Friend Flicka and Green Grass of Wyoming, inspired her. She moved to California when she was 21, and hasn’t left the West since.

Fleming began adopting horses after a traumatic riding experience in 1997, when her horse, Luby, unexpectedly had a heart attack and died. “It was brutal. It was in the middle of nowhere … we had to strip off all of the saddles and walk away,” she recalled. “So, it took me a long time to figure out, what am I supposed to do with that experience? I thought, Well, I’ll just take in a couple of needy horses, and that’s blossomed.”

Fleming owns 1,300 acres, 1,000 of which are devoted to pasturing horses. She has adopted from numerous agencies, and her horses have come from across the West, including Wyoming, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah.

Horses Rosa, left, and Annie originated from the Navajo Nation, which on occasion ships horses to Mexico and Canada for slaughter. Fleming feels rewarded knowing her horses avoid such outcomes. “[To see them] so happy out there and hanging out with them … [and to be able] to give them a one-eighty, I get really emotional,” she said.

This story originally appeared in the Bitterroot newsletter.