The morning after the 2016 election, April Ignacio was shaken awake by her fifth-grader. Ignacio is a member of southern Arizona’s Tohono O’odham tribe, whose ancestral homeland stretches from Arizona into the northern Mexican state of Sonora. Today’s Tohono O’odham Nation sits on some 60 miles of U.S.-Mexico border, and the newly elected president, Donald Trump, had promised a wall that could cut off access to burial sites, pilgrimage trails, sacred lands and some 2,000 tribal members on the other side.

Ignacio’s son wanted to know: What did it all mean?

“It was just that fear already being instilled in him, even as a young child — that’s what I remember,” Ignacio, 36, said. “How was I going to break that down for him?”

Everyone had questions. So Ignacio and a circle of friends started calling up tribal leaders and legal experts to find the answers. In February 2017, a packed community forum about the wall marked the birth of their grassroots organization, Indivisible Tohono.

“It all started as a group of four women,” Ignacio said. “We are all mothers, and our ideology was just to make sure everyone was okay.”

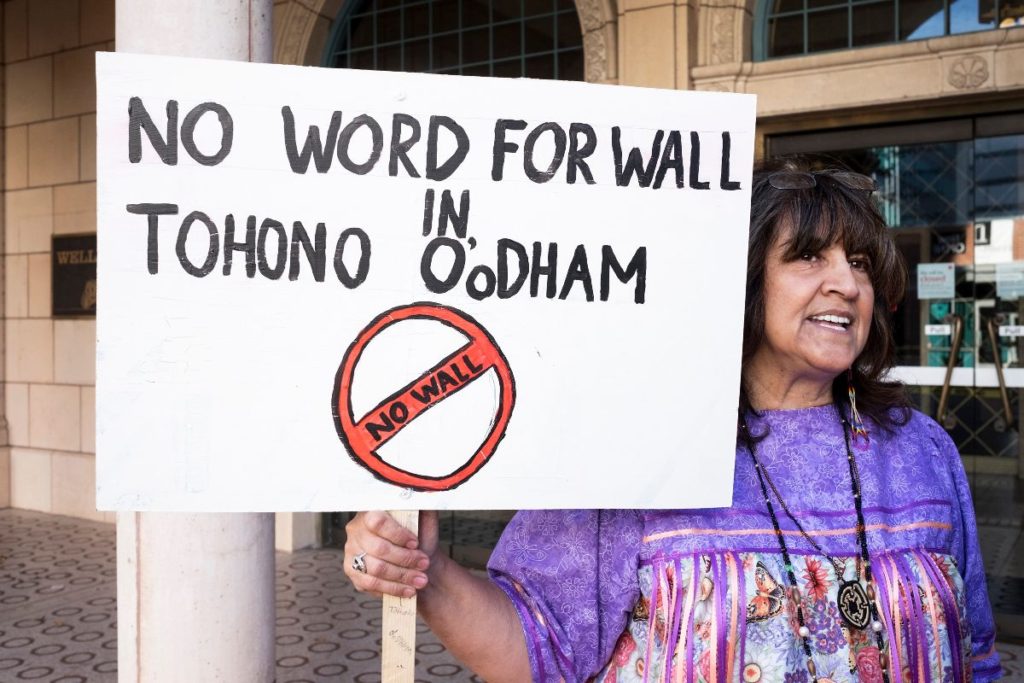

What began as a reaction to the Trump presidency has expanded to advocacy for voting access, community support, and justice for murdered and missing indigenous women. The tribe’s opposition to Trump’s proposed wall has garnered headlines, but that exposure has been one-dimensional. To broaden understanding of their causes, and the tribe itself, the group coordinated an indigenous gathering at the Tucson Women’s March on January 20.

Ignacio stands in front of a group of Native women at the Tucson Women’s March on Sunday, January 20. “We are committed to making Indigenous people more visible, as we have often been ignored, forgotten or even erased from the public eye,” Indivisible Tohono co-founder Gabriella Cazares-Kelly wrote ahead of the event last month. “We’re still here, and we’re leading the way.” Indeed, the indigenous cohort was at the front of the march, which took place on traditional Tohono O’odham land.

All told, Ignacio estimates some 500 Native Americans took part in the event. Indivisible Tohono invited over 30 toka teams from across the Tohono O’odham Nation to lead the Tucson march. Toka is a game traditionally played by women and uses sticks and balls made of mesquite trees from the Sonoran Desert. In a march where myriad communities championed a host of issues, Ignacio said toka was a uniting thread. “We have one area that is dedicated to the woman on our reservation, and that is the toka field,” she said.

Cathy Wilson, 64, attended the march as a show of solidarity for fellow Tohono O’odham tribal members. “This is a chance to feel empowered and to empower others,” she said. “We’re asking that people realize we are still here; we are not invisible.”

Demonstrators used the event to spotlight the issue of murdered and missing indigenous women in U.S. cities and tribal lands, including the Tohono O’odham Nation. “My grandmother was killed, and her murder was never solved,” 15-year-old Diavian Zazueta (right) said. “It means a lot for us to be here.”

Tohono O’odham elders and youth leaders alike joined the march. “We’re out here to support Native American issues that we’ve always known about but are only now getting brought up [because of the wall],” Jasmine Johnson, 15, said. “We are marching for our ancestors and our youth.”

Over the last two years, Indivisible Tohono has grown to a 9-member team. Its actions elevate Native issues and representation beyond what the country’s founders envisioned, as evident in the Declaration of Independence’s description of Native people as “merciless Indian savages.” Indivisible Tohono leads voter registration events, and their candidate forum ahead of the 2018 midterms was the first event of its kind held in the Tohono O’odham Nation.

Ignacio says many Tohono O’odham community members feel disconnected from tribal leadership and Arizona representatives. Activists are working to form a Native caucus, with the goal of one day getting a Tohono O’odham representative elected to the state legislature. But pushing for more recognition hasn’t been easy. “These spaces make us uncomfortable because we’ve never been in them before,” Ignacio said. “We have to put ourselves in these spaces in order to create opportunities for our own people.”

This story originally appeared in the Bitterroot newsletter.