Bitterroot is partnering with the The Modern West podcast to examine the resilience of Western people and towns. This is Part 2 in the series.

Part 1: The Blackfoot Watershed: Montana’s Laboratory for Rural Collaboration

Part 3: Out of the Wilderness: Guides are Teaming Up to Prevent Suicides

Part 4: This Oregon Town is a Hotbed of Latinx Political Leadership

Part 5: Colville, Washington Survived the Timber Wars. Now It’s Tackling Wildfire

Business this year has bustled at 505 Cycles, a bike shop in Farmington, New Mexico owned by Dale and Rhonda Davis. COVID-19 related travel restrictions, business closures, and social-distancing measures have pushed people outdoors, and Davis has seen an influx of customers. Visitors from out-of-state stop by to purchase maps or rent bikes, while local families will stop in and buy four or five bikes at a time.

“The mountain biking and cycling business went absolutely through the roof, and that was nationwide,” Dale said. “It drove a lot of business to us.”

The Davises, like the city they live in, straddle two economic worlds. Rhonda and Dale can’t make ends meet off the bike shop alone — Dale also manages a truck dealership, and Rhonda teaches wellness courses at San Juan College. The semis and 18-wheelers Dale sells are used by the region’s oil and gas industry, the taxes on which fund the college where Rhonda teaches. This couple has fully embraced outdoor recreation, which some view as a lifeline for Farmington and other Western towns, but they still lean on the fossil fuel industry for much of their income.

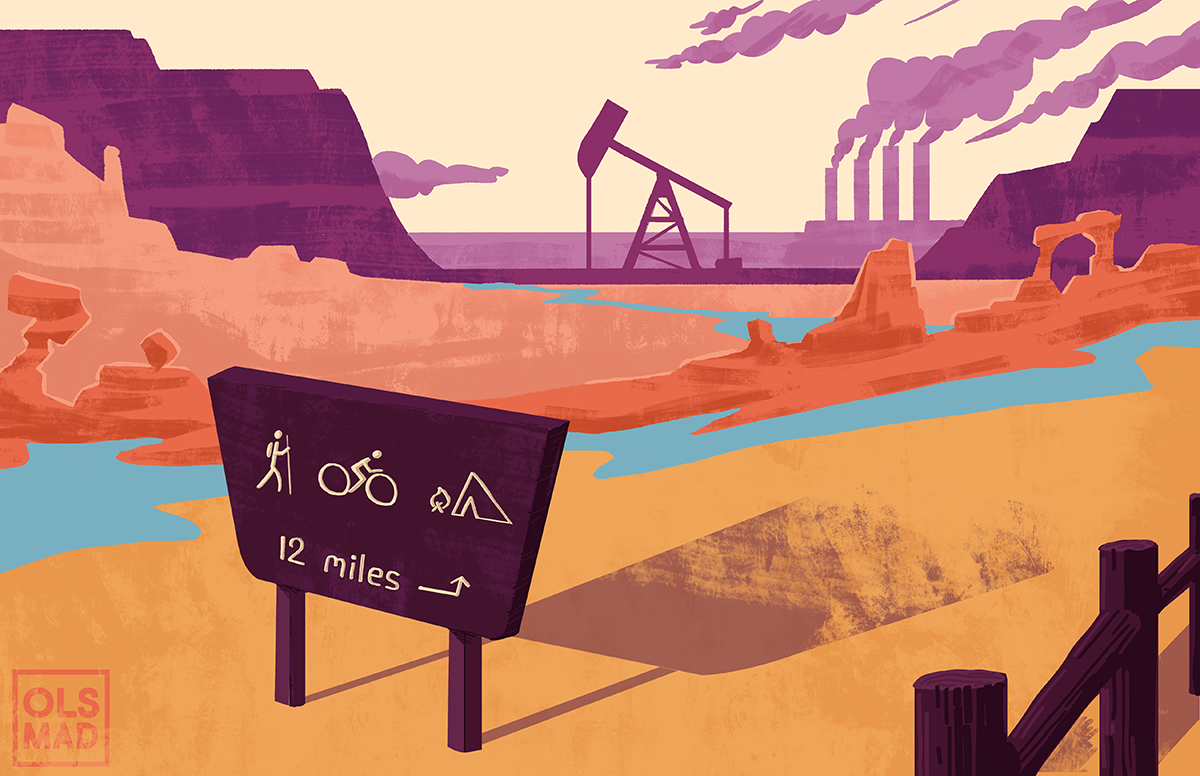

Farmington is trying to strike a similar balance between recreation and extraction. This Four Corners city of 45,000 has long been an oil and gas town, but business never fully recovered after prices fell in 2014. In addition, the San Juan Generating Station, one of the country’s largest coal-fired power plants, has retired two of its four units; the others are scheduled to close in 2022.

Many small towns reliant on logging, mining, or drilling have looked to outdoor recreation after downturns. There’s the allure of big numbers: the Bureau of Economic Analysis says it’s a $472 billion industry nationwide, and that total is growing fast. Farmington’s transformation so far, and its long-term plans, show both the promise and the limits of this prospect. Embracing biking, hiking, ATVs, and the like will work, Farmington Mayor Nate Duckett said, but it will work better if the city can keep the local coal mine and coal-fired power plant alive by pioneering carbon-capture technology.

“You’re watching jobs leave from your oil and gas companies that are here, and you’re concerned about what your future holds,” Duckett said. “That really became the point of saying, ‘OK, we’ve got to do something new, and we’re going to have to change our trajectory.’ We’re trying to keep our city alive.”

In early 2014, crude oil was trading for about $100 a barrel. But that summer, prices began to plunge. Come January 2015, oil was trading for less than $50 a barrel; a year later, the price was hovering around $30. Rigs shut down across Farmington’s oil and gas fields, and the area saw the nation’s biggest jump in unemployment.

Town leaders knew something had to change. They studied small-town comeback stories, examining how Durango, Moab, and others as far afield as West Virginia were able to turn things around. Officials surveyed residents about what kept them here, and what might draw newcomers.

“It came out clearly that people here love the outdoors,” said Tonya Stinson, executive director of the Farmington Convention and Visitors Bureau.

There’s a lot to love. The Animas and San Juan rivers join in town, offering dueling float-trip options through red rock canyons, kayaking and tubing, and top-notch fly fishing. Biking and hiking trails maze through canyons and over juniper-carpeted mesas. Some trails call for fat bikes with tires wide enough to float over sandy stretches, while others swoop over slickrock and thread striated blonde boulders. A hiker who knows where to look — or has a guide to show the way — could spot one natural arch after another, or linger among 1,000 years of Puebloan history at Chaco Culture National Historical Park and outlier sites. Jeeps crawl over sandstone ledges in stretches of public land surrounding the city. Farmington Lake’s ready-made swimming beach lures swimmers and stand-up paddleboarders.

“There’s essentially 10 sectors of outdoor recreation, and we hit all of them except saltwater sports,” said Warren Unsicker, the city’s director of economic development.

From our sponsor

A new season of The Modern West podcast is exploring the evolving identity of the West though ghost towns past and present — and asking, why should we care if America’s small towns disappear?

Following surveys and focus groups that began in 2014, the city put together an Outdoor Recreation Industry Initiative. The effort has reached from the basic — like adding wayfinding signs — to the meta, settling on a city motto of “Jolt Your Journey” to suggest positive surprises ahead.

“When the initiative came in to try to build outdoor recreation as a prime revenue generator for our area … that’s when you saw things starting to grow,” Dale Davis, the owner of 505 Cyles, said. “You could feel the change in the community.”

Signs and slogans alone, though, don’t yield new employers. To that end, the ORII in 2018 held its first BaseCamp event, a one-day blitz designed to help fledgling outdoor businesses. BaseCamp participants receive stats on the outdoor industry and meet fellow entrepreneurs. They learn about resources for startups and the business incubator at San Juan College, and how to obtain permits from the local Bureau of Land Management office. Those considering the manufacturing realm tour a maker space at the college to spark ideas. A partnership between the city and the college also offers marketing services to new businesses.

In addition, the city is investing in key infrastructure. Using funds from a sales-tax increase approved in 2018, it bought a dilapidated building for $60,000 and renovated it to house start-up businesses. The first tenants, an off-road vehicle maintenance, repair, and rescue business, Black Bear Unlimited, and a rafting company, Desert River Guides, are just opening up shop. The city and the BLM are working on a mountain bike skills park and flow trail, and are pursuing a grant to build a pump track. Farmington has spent nearly $860,000 to link almost 10 miles of riverfront trails, and plans to build a wave feature in the Animas River. The city may lack saltwater, as Unsicker noted, but the wave means folks could still surf. Unsicker says the programs are still too new to quantify results, but bike shops, tour companies, and fabrication firms are popping up in town.

Outdoor recreation isn’t intended to fuel the city’s economy on its own. The Farmington Chamber of Commerce is leading a campaign to attract retirees by touting, among other things, the area’s distinct but mild seasons, lower cost of living, and a noted municipal golf course. A downtown revitalization will widen sidewalks and improve landscaping, with the goal of getting people to linger at restaurants and breweries after a day on the trails.

Agriculture is another component of a regional diversification strategy. The Four Corners area was once a hotbed of apple production, and a trained eye can recognize cultivated trees, some of which are so obscure they’re unknown to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The folks running the Montezuma Orchard Restoration Project, based just north in Cortez, Colorado, envision livestock grazing on drought-tolerant wildflowers and grasses between trees that produce apples for a local cider press.

“We’re going to be able to rebuild the orchard economy in the Southwest by bringing back these old varieties that grew here, and grew well, for … the last 120, 140 years,” said Jude Schuenemeyer, who co-directs the project with his wife, Addie. “The average person, even with a few acres, can put in some trees and have it be profitable.”

Growing new economic stems requires a sturdy trunk, and many believe the San Juan Generating Station — despite its precarious future — will fulfill that role.

The power plant, which began operating in the 1970s, and its associated coal mine employ 657 people, 40 percent of them Navajo, according to a Four Corners Economic Development, Inc. study. To meet state and federal air quality requirements, the Public Service Company of New Mexico — the plant’s majority owner — installed pollution controls on two of the plant’s four units in 2016, and closed the other two as part of a settlement the next year. Then, in 2017, PNM announced plans to close the remaining units by 2022, sending Farmington scrambling to fill the forthcoming gaps in its tax and employment base.

City officials see hope in plans by Enchant Energy to capture carbon dioxide emissions from the power plant. Doing so would cut carbon emissions from 2,200 tons to 294 tons per megawatt hour, and the carbon dioxide would either be stored underground or piped to the opposite corner of New Mexico, where it would be used as a hydraulic fracturing additive. A U.S. Department of Energy cooperative funding agreement will send $22 million the project’s way via the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, which has studied the carbon-capture technology since 2003.

“Farmington has big challenges,” said Bob Balch, director of the Petroleum Recovery Research Center at New Mexico Tech. “It’s just piling on and piling on and piling on — where do you stop the bleeding? This is a place where you could stop the bleeding.”

Opponents question the financial viability and technical feasibility of the effort, but those in support of Enchant’s plan say the power plant is too valuable to just let it close.

“That project is really geared to sustain 1,500 direct and indirect jobs at the power plant and at the coal mine,” Duckett said, jobs that command $80,000 to $100,000 salaries and pump millions in taxes into state and local coffers, he added. Research from O’Donnell Economics and Strategy tallied mill levies and property tax revenue from the power plant and mine at more than $9 million a year.

Farmington’s outdoor recreation plans could move forward without coal, but losing the generating station entirely would mean fewer local customers with disposable income, and less tax revenue to invest. It’s unlikely bike shops and tour companies could produce similarly high-paying jobs, Unsicker said, but outdoor manufacturing companies like those taking shape at the maker space and business incubators could yield jobs with higher and more stable salaries.

The prevailing sentiment is one of hope. Dale Davis hopes to one day run 505 Cycles full-time. “We’ve had struggles, but this is an area that’s been through those struggles before,” he said. “This is one of the first times you’ve seen so much pro-activity to try to bring new industry to the area and to try to grow ourselves so we’re not so dependent on one industry. So yeah, I think we’re struggling, and we have been for a while. But the things we’re doing now, I think you’ll see a whole new Farmington, New Mexico, 10 years from now.

“You can’t just throw your hands up and go, ‘There’s nothing I can do,’” he continued. “There are so many things that can be done, and those are the things we’re doing.”