To glimpse the environmental movement’s future, look to Rudy Zamora. Born in Mexico in 1987, Zamora’s parents brought him to the U.S. when he was 3. With protection under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, Zamora graduated from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and worked as an organizer for groups focusing on gun violence, immigration, and education in the state. The birth of his first child, in 2014, got Zamora thinking more about climate and the environment; that concern was amplified when his son was later diagnosed with asthma. From then on, it became clear to Zamora that protecting the health and wellbeing of his community started with clean air and water.

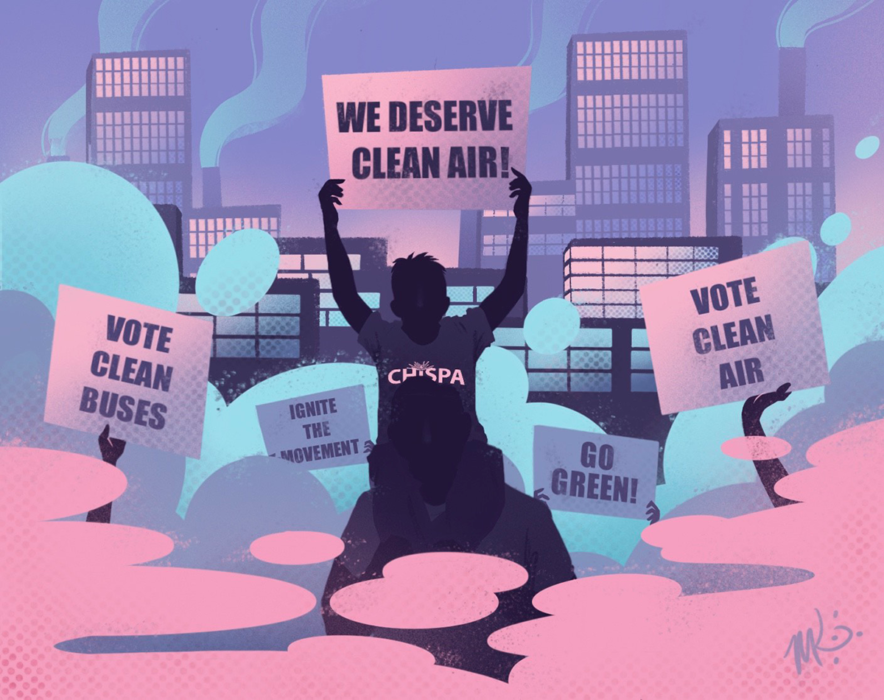

Today, Zamora is the program director for the Nevada branch of Chispa, the League of Conservation Voters’ Latinx outreach arm. In his role, Zamora educates community members about environmental issues and policies, and helps his grassroots volunteers present solutions to state and local leaders. Chispa may have an environmental focus, but it takes an intersectional approach. That means Zamora dedicates a good deal of attention to climate change and clean transportation, but also to voting rights, census counts, and COVID-19 disparities.

“The environment is one of those issues we can talk about in an intersectional way,” Zamora told me. “The environment affects immigration … it’s going to affect our jobs, it’s going to affect our migrant workers, it’s going to affect our education. Climate ties everything together.”

For decades, environmental and conservation organizations have pitched grand ideas — a nationwide carbon tax, say, or large-scale land preservation miles from any big city. But Chispa’s approach represents a more equitable brand of environmentalism, one driven by those affected most by climate change. By focusing on local environmental issues and the democratic process, Chispa’s Latinx staffers and volunteers in five states — Arizona, Nevada, and Colorado among them — are gradually nudging the movement in a more just direction.

“The large, mainstream environmental organizations — primarily white-led and serving white constituencies — had just not been engaging with communities of color,” said Jennifer Allen Aroz, LCV’s senior vice president of community engagement who founded Chispa in 2014. “They were missing out on the folks who actually care the most about environmental action.”

Polls suggest that people of color are more concerned about climate change than are white folks, and that’s in part because they suffer the brunt of society’s environmental misdeeds. According to the American Lung Association, Western cities have some of the worst air in the country. Hispanic folks represent the largest ethnic group in five of the 10 cities with the highest levels of ozone pollution, and in majority-white cities, pollution is worse in neighborhoods occupied by people of color.

In 2015, researchers from the universities of Michigan and Montana found that racial composition of an area is the strongest predictor of where polluting industrial facilities are located. Discriminatory policies and business practices have, over decades, effectively segregated cities, which has meant freeways, factories, waste sites, and other facilities that add to a locale’s toxicity are often built where Black, Native American, or Latinx people live. Telegraphing this dynamic in Phoenix, a team of Arizona State University researchers found that “historic racist discourses and practices and their effects on land use decisions have been literally inscribed on the landscape” of the city.

“To promote a century of industrialization adjacent to low-income neighborhoods,” the authors wrote, “without concern for the well being of residents or any substantial investment in housing for its residents is environmental racism.”

Living in these areas has long-term ramifications. Research out of the University of Southern California found that kids who live closer to Los Angeles’ freeways have higher rates of asthma and other respiratory illnesses. Such health risks have become starkly apparent during the COVID-19 crisis, in which American Indian, Black, and Latinx folks are all being hospitalized at higher rates than white people.

To Allen Aroz, this constitutes not just an environmental injustice, but a political one as well. If Latinx people are disproportionately feeling the impacts of pollution and climate change, they should be at the forefront of policy decisions. That’s why Chispa adopted a grassroots approach in which local solutions emerge from the ground up.

Critical to this work are Chispa’s fleet of Promotores, trained volunteers who serve as a kind of community climate liaison. One such volunteer is Juan Carlos Guardado, who works with Chispa Nevada in Las Vegas. Before the pandemic hit, Guardado would gather signatures in support of electric school buses. At local community centers and churches, he would explain how retreating glaciers are connected to Nevada’s worsening heat. With community gathering spots now shuttered, he’s doing it all virtually.

Guardado moved to the U.S. from El Salvador in 2014, and didn’t worry much about climate policy until a Chispa organizer knocked on his door a year later. After learning more about how climate change and local pollution could affect him and his daughter, now 4, he decided to take action.

“I think about how kids who are being transported in school buses could develop respiratory illnesses like asthma,” Guardado said through an interpreter. “If we don’t take action now to address this issue, my daughter will pay the consequence in the future.”

One step Guardado, who became a naturalized citizen this summer, will be taking for the first time this year is voting. Political agency is a common thread in Chispa’s work. In Nevada, for instance, Chispa shuttled community members to the state capitol in Carson City to testify in favor of a clean-energy mandate, passed in 2019, and the adoption of cleaner vehicle emission standards. It held Spanish-language classes ahead of the state caucuses in February, and representatives at caucus locations around the state made sure climate change was part of the discussion. Ahead of June’s primary, Chispa led vote-by mail tutorials. Similar measures are planned for the November election, and the group has spent much of 2020 pressing community members to participate in the Census count.

“We are educating and mobilizing Latinos. We are putting climate at the dinner table within our communities,” Zamora said. “It’s crucial that we not only face the climate crisis, but that we address it through a racial justice lens.”

Another prominent Chispa initiative, Clean Buses for Healthy Niños, is doing just that. In Arizona, for instance, some 300,000 students ride to school aboard a bus, most of which run on diesel fuel. Swap those to electric motors, organizers figure, and you’d eliminate direct emissions from one of the largest public transportation fleets in the state.

Last spring, Chispa Arizona notched the clean bus campaign’s fist victory. With Chispa’s help, members of the South Mountain High School cross-country team spent the better part of a year lobbying the Phoenix Union School District, Arizona’s largest, to buy electric buses. Students in industrial south Phoenix, they explained, breathe unhealthy air throughout the day; they should at least get a reprieve when they ride to school. In April 2019, the PUSD board approved its first purchase of an electric school bus, and said it would establish a pilot program to buy more.

“I like to stand up for my community because they deserve a better environment, a better place to live in,” Monica Aceves, at the time one of Chispa’s student volunteers, told The Arizona Republic.

To Allen Aroz, that type of local action primes more systemic change. “Climate change is massive … the solutions can feel really complex,” she said. “You can’t immediately jump in and take on Goliath. It’s about taking some smaller steps, but ones that are significant and impactful. And the iconic yellow school bus is a great first step.”

There’s an area of Las Vegas, near Zamora’s childhood home, that shows the potential of Chispa’s approach. Just east of downtown, two community centers, a middle school, and an elementary school are all located within blocks of U.S. Route 95. “Our communities are living off that highway, and getting all that pollution from those cars,” Zamora said. “That’s why we’re mobilizing to ensure we are getting clean air and clean water — because our families are the ones that are disproportionately affected by pollution, and by the choices people are making for us.”

By focusing on local issues like clean school buses, Zamora and others are ensuring such choices are made in conjunction with the Latinx community. “It’s time,” he said, “to have our voices heard.”