This story was produced with support from the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.

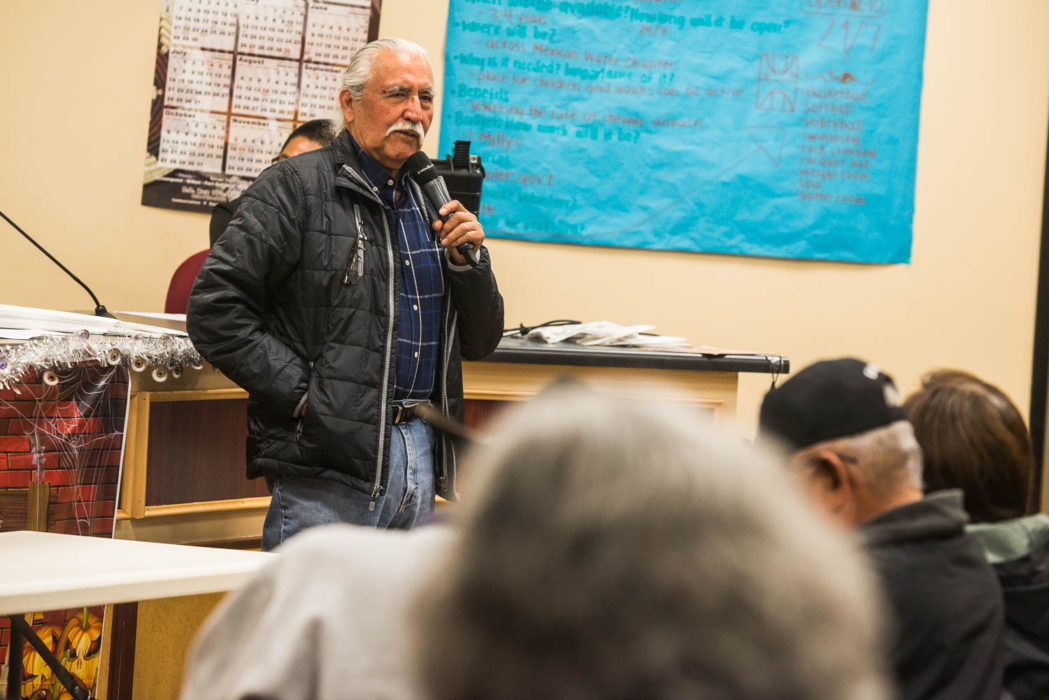

On a cool but sunny afternoon last November, about 100 people gathered in the Mexican Water Chapter House, a community center on the Navajo Nation. Willie Grayeyes took the podium, and began to explain how a ballot initiative in the upcoming election would determine their political future in Utah’s San Juan County. He told the audience that Proposition 10 could dilute hard-won Navajo representation in the county government. Then Grayeyes, typically known for his quiet nature, raised his fist and chanted in unison with the packed assembly room: “Dooda 10! Dooda 10!” — No on 10 in the Diné language.

In 2018, Grayeyes won a historic election in which he and Kenneth Maryboy became the first Navajo-majority commission in the history of San Juan County, a 7,900 square-mile expanse in southeastern Utah that overlaps with a portion of the Navajo Nation. His commission seat — his very candidacy — took extraordinary measures to secure, and that political power was again at risk. If enacted, Proposition 10 would have launched a study to consider adding two positions to the county commission, which Navajo politicians and activists felt could undermine political representation achieved after decades of canvassing and lawsuits.

San Juan County’s 17,000 residents are primarily Navajo Nation members or descendents of white Mormon settlers. Despite representing a slight majority of the population, Navajo people here have dealt with systemic disenfranchisement and repression for generations. But events in recent years kicked off a political emergence that has reshaped politics in this part of the West.

The 2018 election was preceded by a landmark court ruling that San Juan County’s voting districts discriminated against Navajo residents. Not only was the county required to draw up new, more equitable district maps, it had to provide in-person polling and translation assistance. In addition, voters were energized when President Donald Trump slashed the size of the newly established Bears Ears National Monument by more than 80 percent, incensing local Native Americans who had spent the better part of a decade lobbying for its protection.

Outrage, newfound enfranchisement, and an unprecedented get-out-the-vote effort propelled Maryboy and Grayeyes into office. Now, their goal is to restore protection of a sacred landscape and provide the services that their community has long been denied.

Among the organizations helping them is Utah Diné Bikéyah, the nonprofit that first pushed for protection of Bears Ears. Angelo Baca, UDB’s cultural resources coordinator, said that Navajo folks never saw how county government could benefit them. But recent elections have, he said, flipped the system “on its head.”

“People who are on the bottom rung of the ladder for socioeconomic conditions are actually throwing their hat in the ring to see if they can get into these politically powerful, influential positions, and see if they can make some change,” Baca said.

Just days after Grayeyes rallied folks at the Mexican Water Chapter House, the trend continued. Voters rejected Proposition 10, ensuring the state’s first majority-Native county commission would remain for at least a few more years.

Communities such as Mexican Hat, Aneth, and Monument Valley in the south portion of San Juan County, which overlaps with the Navajo Nation, have long received less investment than majority-white towns of Blanding and Monticello in the north. A consistent lack of funding for roads, schools, health care, running water, electricity, and sanitation have left many Utah Navajo living in subsistence conditions unseen in other parts of the United States. Without political allies in county leadership, they had no way to remedy the situation.

A major reason for the disparity is that about 60 percent of Navajo residents were packed into a single voting district when the original lines were drawn in 1984. For decades, predominantly white commissions denied funding for projects on the Navajo Nation, arguing it was the responsibility of the tribe or the federal government to fund public services on the reservation.

“The Native Americans are very upset, because they’ve been running against a wall all these years,” Maryboy said.

Following the 2010 Census, the Navajo Nation asked San Juan County to undergo redistricting, but county leaders declined to do so. So, in 2012, the tribe filed suit, claiming the county voting districts were racially motivated and violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution. After years of litigation, U.S. District Judge Robert Shelby ruled in 2016 that the county indeed discriminated against Native American voters, and would have to redraw its boundaries.

“Keeping an election district in place for decades without regular reconsideration is unusual in any context,” Shelby wrote in his opinion. “But when the asserted justification for this inertia is a racial classification, it offends basic democratic principles.”

In December 2017, Shelby approved three new voting districts and ordered a special election to be held the following year; every county commission seat would be on the ballot. Two districts had clear majorities of Navajo and white residents, respectively, and a third was more evenly weighted. Thanks to a separate settlement, the county also established in-person voting locations on the reservation and provided translation assistance for voters who speak Diné. In 2014 and 2016, the county switched to mail-in ballots, which were of little use to Navajo who lacked reliable postal service or the ability to understand an English-only ballot.

“I thought it was a very good judgement. A very good ruling. Finally, we can begin to see some progress with some of the goods and services provided by the county,” said Mark Maryboy, Kenneth’s brother who, in 1986, was the first Navajo elected to the San Juan County Commission.

For the first time since the county was founded in 1880, San Juan’s Navajo residents had an opportunity for proportionate representation. Kenneth Maryboy and Willie Grayeyes emerged from the primaries as Democratic candidates in the south and central districts. Their spots on the ballot were a clear sign that Bears Ears would play a role in the election — both of them were board members of Utah Diné Bikéyah.

Bears Ears — so named for the prominent mesas that crop up above the high-desert landscape — is an area of spiritual and cultural significance for members of the Navajo and other regional tribes, including the Hopi, Ute, and Zuni. It’s a place to gather juniper berries, hunt game, and cut firewood. It’s a site for ceremonies and festivals, and where ancestors are buried.

“Bears Ears is all about protection, conservation, culture, religion, and the future of the people,” said Mark Maryboy.

In 2010, Maryboy started asking elders in the Navajo community which sites around Bears Ears should be protected, and how best to preserve them. That canvassing was the origin of Utah Diné Bikéyah, and the group eventually formulated a Bears Ears protected area. After Utah’s congressional delegation declined to take up the proposal, UDB turned to Southwest tribal governments for help. The resulting Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition petitioned President Barack Obama in 2016 to protect the region.

On December 28 that year, Obama created Bears Ears National Monument, a sweeping, 1.35 million-acre expanse of mountain forests, desert plateaus, and sandstone canyons rich with Native American artifacts and cultural sites. While UDB and many Navajo celebrated the monument’s creation, state politicians were less than enthused. With prodding from Orrin Hatch, the influential former Utah senator, and then-Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, President Donald Trump axed roughly 85 percent from the monument in late 2017. San Juan County’s commissioners, all opposed to the monument at the time, stood by Trump’s side as he signed the executive order in Salt Lake City. Bears Ears, in its original form, lasted less than a year.

“Seven years of work was undone by Trump and Zinke, and it took him less than one month to do that,” Maryboy said of Zinke’s rapid review process. “He never met with us, he never met with the tribe. He met with [opponents], and that’s why they made a decision.”

After the reduction, UDB, members of the Inter-Tribal Coalition, and environmental groups sued the administration, arguing the Antiquities Act authorizes a president only to create a monument, not to reduce or rescind one. The lawsuits are ongoing.

Although then-commissioner Rebecca Benally, a member of the Navajo Nation, opposed the monument, most Native Americans supported Bears Ears. Its reduction brought a bubbling political movement in San Juan County to a full-blown roil — and did so at a time when Navajo votes would matter more than ever. Shelby approved the new voting districts just 18 days after Trump altered Bears Ears. A political upheaval was underway, and Utah Diné Bikéyah’s members were going to usher in the change.

Tara Benally, a UDB volunteer and daughter of board member Mary Benally, was prominent in the get-out-the-vote drive. Benally was no stranger to community work. She had previously built houses on the reservation with Habitat for Humanity, and was protesting in Salt Lake City when Trump downsized the monument her family had worked so hard to protect. In 2018, she joined the Rural Utah Project, a nonprofit supporting marginalized rural communities in the state.

Benally made it clear to her neighbors: voting could help elect a majority-Navajo commission. She and other RUP staff and volunteers would spend the coming months aggressively lobbying their community to vote for Grayeyes and Maryboy. They traveled across the region, from remote homes on the edge of Monument Valley to chapter houses in the heart of Navajo towns.

“We mobilized as quickly as possible,” she said. “We wanted people out there day to day, going to different events, going to clinics. Anywhere that people gathered, whether it was a grocery store or a gas station, we were there, day in and day out.”

Within two months, Benally said, the RUP team helped about 1,600 folks update their voting information or register to vote for the first time. Meanwhile, Maryboy and Grayeyes campaigned on supporting Bears Ears and bringing much-needed infrastructure improvements to Navajo chapters. On election day, more ballots were cast countywide in 2018 than in 2016, a presidential election year, and turnout was further amplified by the in-person polling locations and translation assistance.

The work of Benally and others paid off. That November, Grayeyes won the District 2 seat with 54 percent of the vote, and Maryboy easily secured the third district with 63 percent. Incumbent Bruce Adams took the other seat unopposed.

The election was momentous in the Navajo community. “There is a serious lack of support, a lack of being heard for issues that are happening in these Native communities,” said Davina Smith, a Navajo citizen and a field organizer for the San Juan County Democrats in 2018. “The only way that those issues could be heard is from our two Diné commissioners. Finally. Finally, we’re being heard.”

Soon after taking office, Maryboy and Grayeyes passed a trio of resolutions in support of Bears Ears. One rescinded previous county resolutions, cited by Trump and others, that opposed the monument designation. Another yanked the county from participation in the ongoing Bears Ears lawsuits, and a third voiced support for legislation that would create a 1.9 million acre Bears Ears monument — about 600,000 acres larger than the original, and the size first called for by Utah Diné Bikéyah.

Kenneth Maryboy grew up in a household of 11. He first worked as a welder, but a neck injury forced him into early retirement and a life of politics. In 2001, he was elected to represent the Mexican Water chapter on Navajo Nation Council. Five years later, he would join another governing body by winning a seat on the San Juan County Commission.

During Maryboy’s first two stints on the commission, from 2006 to 2014, fellow commissioners routinely shot down his proposals for infrastructure upgrades and services on the Navajo Nation. Now, as chair, Maryboy has more control of the county budget, but still finds himself limited by the small tax base and a series of lawsuits that depleted the county’s general fund from $7 million in 2015 to less than $1 million.

County staff, Maryboy said, routinely tell him that there’s not enough revenue to support projects in Navajo communities. “They never said that when they went and dipped into the money to hire the attorneys that they were using against us,” he told me.

According to The Salt Lake Tribune, San Juan County spent $4.4 million on legal counsel between 2015 and 2018. A good portion of that was dedicated to the voting-rights suit brought by the Navajo Nation, to which the county must pay another $2.6 million in fees. The county also spent $500,000 lobbying President Trump to shrink the Bears Ears monument.

Some of the county’s legal expenditures were used to fight Grayeyes’ very candidacy. After Grayeyes won his primary, the county clerk for a period removed him from the ballot and rescinded his right to vote, arguing Grayeyes actually lived in Arizona.

Grayeyes lives near the Arizona border and, like many Navajo folks, bounces back and forth between Utah and Arizona, where there is better access to services like groceries and a post office. Grayeyes challenged the county’s action in court, and a judge ruled that he, indeed, lived in Utah, citing his active voting record in the state since the 1990s.

Despite his rough road to the commission, Grayeyes doesn’t hold a grudge. While Maryboy routinely voices frustration with the systemic inequality in San Juan County, Grayeyes hopes to be a more measured, unifying force.

“I don’t want any legacy. All I want to do is do my job, and that’s it,” he said. “My history for myself is not the purpose of my life. It’s representing the people that voted for me.”

The redistricting that catapulted Maryboy and Grayeyes to office didn’t sit well with the majority-white areas of the county, especially in the city of Blanding, which is now divided into two districts. Mayor Joe Lyman, a key supporter of Proposition 10, said that Judge Shelby essentially installed the commissioners.

“I don’t care what race somebody is — I want them to be chosen by the people and not by a judge,” he said in an interview at his business, Cedar Mesa Pottery. “That’s what we feel like we have.”

Commissioner Bruce Adams said Maryboy and Grayeyes haven’t mended any divides. “I don’t see [Grayeyes] doing anything to heal the process,” he said. “What he’s been doing has been exacerbating the whole thing. He isn’t reaching out to any of the conservatives. He’s completely following the liberal agenda.”

The county’s finances have bogged down Grayeyes’ and Maryboy’s agendas; Grayeyes, in particular, has said the county needs to prioritize rebuilding the general fund over new projects. But some progress has been made. In February, for instance, Maryboy finalized an agreement with the Navajo Nation to fund road maintenance in San Juan County. And commission meetings, once held exclusively in the north, are now taking place at times in Navajo communities, and are live-streamed on Facebook.

Navajo residents like Darlene Valentine, of Mexican Water, are cautiously optimistic. Even if Grayeyes and Maryboy aren’t able to commit to their campaign promises, she said, they’re at least bringing issues to light.

“It’s hard to say it’s changing in a good way or bad way,” she told me. “But now that they’ve put out everything on the table … it’s a starting point.”

Mark Maryboy was similarly forward-looking about his brother’s commission majority. “You can’t stop thinking about the challenges that lie ahead,” he said. “It takes decades before you begin to see a real positive result.”

One immediate impact, though, is that Grayeyes and Maryboy have invigorated Navajo voters.

“We’ve been waiting for this for so long,” Benally said. “This is our future. If we can be the example for the Navajo, we can be the example for other nations as well. Now is the time for us Native Americans to hit them at the polling places.”

Utah Diné Bikéyah’s purview has expanded well beyond Bears Ears. Its members are helping the Rural Utah Project and the Navajo Nation Addressing Authority add more Native Americans to the voting rolls and ensuring more accurate census counts — all measures that bolster enfranchisement Navajo folks have long been lacking. When COVID-19 hit the reservation, the group provided information and helped coordinate coronavirus testing. For those struggling to source food, UDB distributed seeds and sheep to the reservation.

And, if Donald Trump is defeated in November’s election, UDB plans to petition for the re-establishment of Bears Ears National Monument. This time, they’ll have the San Juan County Commission behind them.

Editor’s note: An earlier caption mislabeled Mark Maryboy as Kenneth Maryboy. We regret the error.