It didn’t happen with the speed of the novel coronavirus, but the HIV and AIDS epidemic devastated the United States to a level COVID-19 hopefully will never match. The White House is warning 200,000 Americans could die from our latest pandemic; AIDS has killed more than 675,000 in the U.S. since it emerged in 1981. The Centers for Disease Control estimates 1.1 million Americans have HIV, 14 percent of whom have no idea.

To Laurie Marhoefer, an associate professor of history at the University of Washington, the novel coronavirus is “like the AIDS crisis on fast forward.” Marhoefer specializes in LGBTQ politics, and as the COVID-19 outbreak unfolded in Washington, she noticed the same othering, slow federal response, and denial that exacerbated the HIV and AIDS crisis in the 1980s.

Read the rest of our coverage of the novel coronavirus

I caught up with Marhoefer to discuss the similarities and differences between the two outbreaks. Our conversation has been edited for clarity.

Jake Bullinger: At what point did the coronavirus outbreak start to remind you of the HIV crisis?

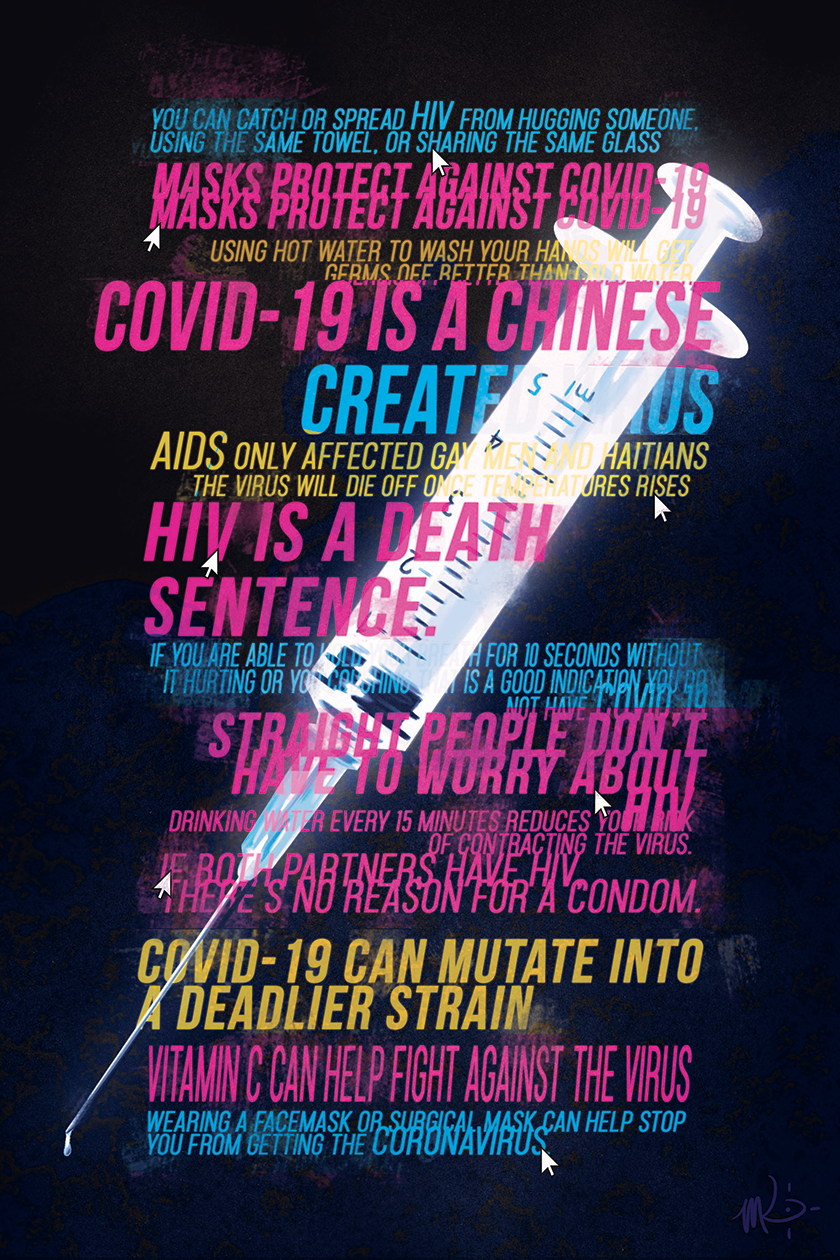

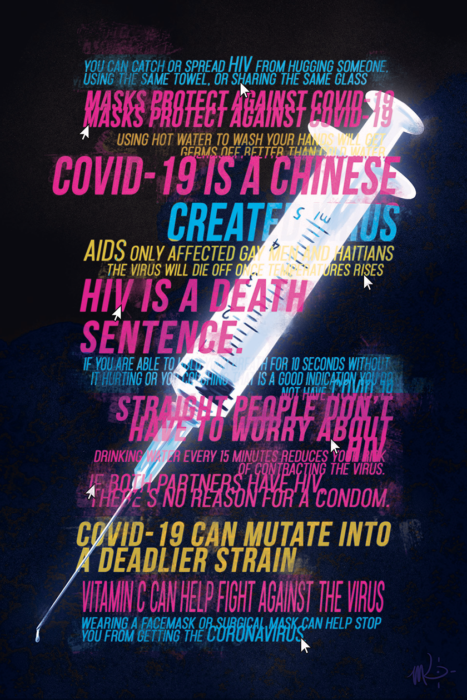

Laurie Marhoefer: When we started getting cases in Seattle, there were these waves of denial and distancing from some people, and then, on the other hand, panic. And the way information was flowing — good information, bad information, misinformation — started to really remind me of the early years of the AIDS crisis.

Compare and contrast the misinformation associated with the two outbreaks, if you will.

In the first moments in both cases, there just wasn’t great science. There are big unknowns about the novel coronavirus, as we’re having this conversation, that remind me a lot of unknowns about HIV. Like questions about how transmissible it is. If you don’t have symptoms, are you transmissible? We still don’t know that about the coronavirus.

But with the novel coronavirus, we’re getting that information faster. With HIV, it took years to get good information about how to have safe sex, how to protect yourself. We know now that you can transmit HIV if you’re not symptomatic, but it took a lot of time to figure that out. In the case of HIV, there wasn’t enough research interest. For the novel coronavirus, the issue was more that there hasn’t been enough time.

There’s also bad information swirling around, which reminds me of the HIV crisis. Two weeks ago, I overheard someone asking their pharmacist if COVID-19 was just like the flu, and the pharmacist was noncommittal. I was like, Oh my god — just say no! It’s not the flu!

When there’s a lack of information and misinformation, people want to believe the less-scary stuff. With HIV, people wanted to believe they could tell if someone was HIV-positive just by looking at them. And the person at the pharmacy just wanted to believe this was the flu. So there’s this swirl of denial, and the slow federal response has reminded me of the AIDS crisis.

So how does the Trump administration’s handling of the coronavirus compare with Ronald Reagan’s treatment of HIV in the 1980s?

The first reports of HIV were in this country, so we had a special opportunity to act fast. And the federal government just ignored it for a couple of years. Look at the money they were spending on research, funding of the CDC — the funding levels were really low for the first couple of years, and Reagan had already slashed federal budgets. People often say Reagan didn’t say anything in public until years into the pandemic — it seems like he wasn’t even thinking about it until Rock Hudson died in 1985.

You look at early press conferences, and reporters would ask Reagan’s press secretary about HIV. You can read the transcripts — he just makes a joke about it and moves on. This is a disease that has killed about 32 million people since then. That kind of inaction just compounded the catastrophe.

But I’d say Trump is a lot worse than Reagan was on HIV. Trump reminds me of Thabo Mbeki, who was president of South Africa in the 2000s. Mbeki decided that, basically, all the science on AIDS was wrong, and then failed to use the state to facilitate the delivery of life-saving drugs to South Africa, resulting in the deaths of probably thousands of South Africans who were HIV-positive and could have lived on antiretrovirals. Mbeki’s failure on this is a really troubling example of how, as AIDS activists taught us in the 1980s, medicine is political.

Trump’s failure to quickly use the federal government to coordinate and facilitate a response to novel coronavirus now strikes me as similar. He made dubious claims about the science, and then refused to use the state to act. Trump’s failure here has already cost lives.

You wrote that the notion of “risk groups” — categories of people who are perceived to be more susceptible to, or the cause of, an outbreak — can complicate public health measures. How has that played out with the coronavirus?

There’s a real danger of people deciding, well, the coronavirus came from Wuhan, it’s their fault, and everybody who looks Chinese could be a risk. That kind of thinking is out there; it’s coming from politicians. That’s part of the reason they weren’t taking more action more quickly. It’s racist and it’s wrong, but it’s also dangerous.

It hasn’t been as pronounced as it was in the history of AIDS. When I researched this, I was surprised how strong the risk group effect was, and how long it lasted. In 1985, the West German press had reports of forced quarantines of gay men.

It did not take long for there to be reports of people dying of AIDS who were not gay men, but they were kind of explained away. Media focused on gay men as a risk group, Haitians and Haitian-Americans, people who did sex work, and people who ingested drugs. That narrative began early, and stuck around for years.

The effect hasn’t been quite as bad with the novel coronavirus, though, because it’s so transmissible and has quickly infected a broad swath of people.

OK, let’s do a thought experiment: If the first confirmed cases were reported in Seattle’s Chinatown-International District instead of a nursing home, would the narrative be different?

Yeah, I think it would. Among white people, there’s a lot of pre-existing racism against Asian people, and there’s a lot of denial about the virus. When denial gets mixed with racism, it can get dangerous. “We’re not them. They’re dangerous,” that type of thing. You definitely saw that in the AIDS crisis. I mean, there was a forced quarantine of Haitian refugees for a while under the Clinton administration. They were held in Guantanamo against their will.

You know, when I teach the AIDS crisis, I often start with something like: Can you imagine if HIV had first been reported in grandmas rather than a group of people who were extremely stigmatized at the time?