This story was published in collaboration with Crosscut, a reader-supported, nonprofit news site serving the Pacific Northwest.

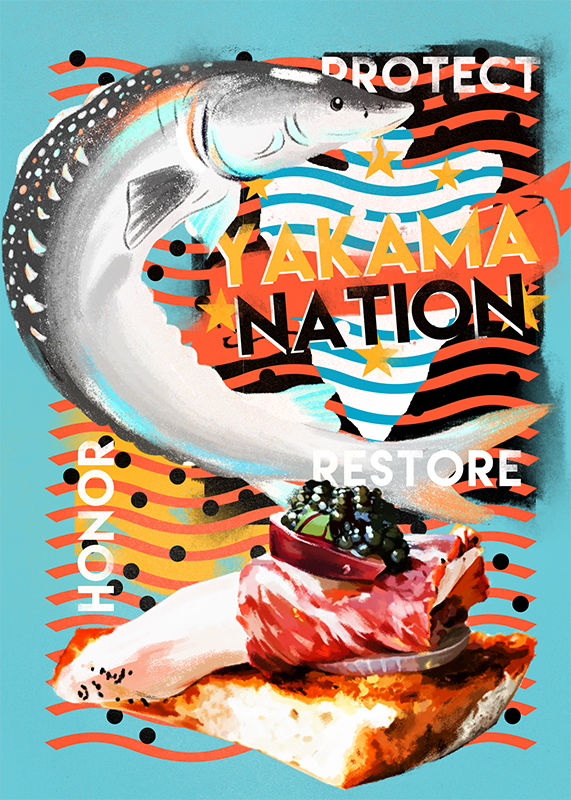

Last December, Crafted Restaurant in Yakima, Washington, served up an Instagram-ready dish of roe sat on a creme fraiche-dappled blini. Festive in presentation, the caviar was in keeping with the holiday season. But these were no ordinary eggs. Instead of black market Caspian Sea beluga caviar, which has been banned in the United States since 2005, guests were enjoying $80-an-ounce caviar sourced from Columbia River white sturgeon.

These nutty pearls were a product of the Yakama Nation’s sturgeon hatchery, the only one to produce commercial caviar in the state that once was an epicenter of the American caviar industry. And if Donella Miller, fish biologist and manager of the Yakama White Sturgeon Management Project has her way, the salt-cured delicacy will help offset the cost of operating the hatchery. Maintaining the Columbia’s white sturgeon fishery is necessary to providing a traditional food for Northwest tribes. But it’s also a harbinger of the overall health of the Columbia River Basin — and the people who call it home.

“[Sturgeon] sustain us, so it’s our responsibility to take care of them and return them,” Miller, an enrolled tribal member, said. “That’s why the tribe is on the forefront of all of these restoration programs and looking out for the long term success of the resource and ensuring that we still have these stocks available for future generations.”

The 14 bands that make up the Yakama Nation have called the Columbia River Basin home for thousands of years. The fertile valley — where today fields of mint, wheat, and hops frame Mount Adams in the distance — sustained them with plentiful elk, deer, wild plants, and, up until the early 1900s, a seemingly never-ending supply of fish.

As salmon returned to the Columbia River, or Nch’i-Wa’na as the Yakama call it, each year to spawn, so too would tribal members. They’d congregate at the roaring Celilo Falls near The Dalles where, standing on precariously thin wooden scaffolding, tribal members would use long-poled dip nets to catch giant chinook from the roaring waters. The preserved salmon could last a tribe months. When salmon runs ended in late fall, the tribes would switch to an alternative food source: Acipenser transmontanus, white sturgeon.

“My aunt tells a story about how her dad, when he would get done fishing in the fall at Celilo, on his last trip home he’d bring back some sturgeon,” Miller said. “He would just keep them wet in burlap and put them in his truck. They had a creek behind his house, and he’d dam up that little creek with rocks and put the sturgeon in there, because they’d still be alive. She said that was their only fresh fish they’d have during the winter.”

Ancestors of the Columbia sturgeon first emerged more than 200 million years ago, during the Triassic Period. One reason they’ve stuck around so long is they’re built like tanks. In lieu of scales, sturgeon have rows of armored plates called scutes that run along their body. A long flat snout conceals a mouth nearer their belly, from which they siphon up prey fish like shad, lamprey, salmon, and smelt. They can live 100 years and grow to 20 feet; big ones tip the scales at 1,500 pounds. One sturgeon could feed an entire village, and for centuries they did.

We can thank German immigrant Bendix Blohm for caviar’s New World popularity, writes Inga Saffron in her book Caviar: The Strange History and Uncertain Future of the World’s Most Coveted Delicacy. Blohm turned caviar into an American industry in the 1870s on the Delaware River. His success exporting sturgeon eggs to sate European Belle Époque bellies quickly ushered in the American Caviar Rush and encouraged Northwest entrepreneurs to follow suit. In 1888, a year before Washington became a state, 94 tons of Columbia River sturgeon were “salted and pickled and the first car of frozen sturgeon shipped east,” according to a 1973 Marine Fisheries Review article.

“A lot of the caviar was sent down to California,” said Dale Sherrow, owner of Seattle Caviar Co. “It was served in the bars like peanuts. Because of the salt content, it would make people drink more.”

Overfishing decimated the Columbia stock. In 1892, 5.5 million pounds of sturgeon were pulled from the Columbia and its tributaries. Just five years later, the catch had fallen below 100,000 pounds — a decline of more than 98 percent. The sturgeon economy went kaput, and the future of the river’s prehistoric fish was in jeopardy. White sturgeon don’t recuperate quickly — they can take 25 years to reach sexual maturity in the wild, and even then, they may spawn only every two to six years. Complicating matters further was a shrinking habitat.

In 1938, the Bonneville Dam turned the Columbia into an electricity-generating powerhouse and facilitated more shipping up the river. Often unable to climb the fish ladders installed for salmon, dams blocked sturgeon migration, preventing the anadromous fish from returning to the Pacific. And that was just the beginning of the dam nightmare.

On March 10, 1956, Yakama fishers watched in horror as Celilo Falls was silenced. At 10 a.m. that day, The Dalles Dam floodgates closed, and the falls disappeared in a matter of hours. “The roar left us just like that,” the late Joe Jay Pinkham, a former Yakama Nation General Council secretary, told the Yakima Herald in 2007. Pinkham said he never fished on the Columbia again.

Today, 31 dams make up the Columbia River Basin hydroelectric system; sturgeon populations are segregated into corresponding reservoirs along the way. The struggle between energy production and the tribes continues. This month, leaders of the Yakama and Lummi nations called for the lower three Columbia River dams to be removed.

Miller and her three-person team at the Yakama Nation Sturgeon Hatchery — one of five sturgeon mitigation hatcheries in the state — is up against all of that history today. Before the hatchery got started, the 44-year-old Miller had only eaten sturgeon twice because their numbers were so low. Sturgeon populations never fully rebounded after the 1890s fishing boom, and habitat fragmentation from dams didn’t make recovery any easier.

“It started to seem like the sturgeon were being lost from the recent [Yakama] culture,” Miller said. With roughly $1 billion spent on salmon recovery efforts in the past 20 years, according to The Seattle Times, and a stable, albeit small, sturgeon population, boosting the bottom-feeder’s numbers hasn’t been a priority.

That changed for the Yakama in 2009, when Miller set up the Nation’s hatchery. There, she and her team live-spawn wild Columbia River white sturgeon to maintain genetic diversity, then tag and release fish into various reservoirs each year. According to the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, or CRITFC, 427,000 juvenile hatchery sturgeon had been released into the Columbia and Snake rivers by various parties between 1990 and 2015.

The result? “If I was to take a thousand-foot look on this thing? Yeah, I would say it’s working,” said Blaine Parker, who leads the CRITFC sturgeon project. In total, more than 630,000 white sturgeon are estimated to live in the Columbia and its tributaries. Upriver, the Colville and Spokane tribes have been operating a sturgeon hatchery since 2002.

Miller values the work for reasons beyond the biological. Raised in a commercial fishing family, she went on to study fisheries resources at the University of Idaho. Miller toured the Columbia Basin after college to learn about other tribes’ sturgeon restoration efforts. “Restoring these stocks and making them available to harvest is kind of bringing that tradition back,” she said.

But it’s expensive work — it costs about $1 million a year to run the hatchery. Yakama white sturgeon, though, are now producing a revenue stream that Miller has been banking on since she started the project 10 years ago: roe. Furthermore, if Miller can keep Yakama caviar coming, it could keep fish in the river safer if traceable eggs deter poaching.

Harvest restrictions implemented in 1950 limited the size of wild-caught sturgeon to 6 feet or smaller, a size at which female sturgeon usually aren’t sexually mature (today, the limit is 54 inches). But poaching remained an issue.

“It wasn’t so uncommon to find a caviar fish, particularly if one could bend, fold, spindle, or mutilate a 6.5-foot fish to fit inside the 6-foot limit,” Steve Parker, technical coordinator for Yakama Nation Fisheries, wrote in an email. With no regulations against selling caviar outside the fish — in today’s market, the fish and caviar must be linked — poachers would catch an oversize female, slice its belly, and abscond with the eggs.

As recently as 2015, high-speed boat chases took place on the Columbia with Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife pursuing black-market bandits hellbent on reaping the possibility of a $200-an-ounce reward for sturgeon eggs. A mature female can carry more than $300,000 worth of roe. The high black-market value over decades decimated European beluga sturgeon stocks, and led some poachers to shift attention to the homegrown variety.

All the more reason for Miller and her team to enter the aquaculture caviar business, especially as the U.S. is forecast to beat France and Italy to become the third-largest legal caviar producer in 2020, according to a 2018 World Wildlife Fund report. A robust legal market would make it harder for poachers to offload their goods.

“It’s all about the paper trail,” Parker said. Yakama Fish and Wildlife rules maintain that all sturgeon caught must be sold intact. “If a wholesaler doesn’t have the supporting documents to prove they bought a legally caught fish that happened to have roe in it, they could lose their license or be fined.”

However it shakes out, one thing is for certain: Miller’s big gamble on caviar is a masterclass in patience. Wild female sturgeon take anywhere from 12 to 25 years to reach sexual maturity. But under just the right conditions in captivity, they can reach fertility in just a decade.

“We’ve only been doing this for 10 years, so we’re just now getting to the point where we have a few ripe females,” said Miller. “It’s a really long-term investment.”

But in the trendy sustainable food world, that investment could pay dividends. Since Yakama caviar comes from sturgeon bred from wild parents, it can be marketed as a locally sourced, Columbia River product. The designation is important to chefs like Crafted’s Dan Koommoo, who also sources sturgeon filets from the Yakama hatchery.

“We were all over it because it is sustainable,” Koommoo said. “The fish isn’t going to waste. We’re buying the fish that the caviar is being made out of. … We’ll take that fish, and then they’ll cure the caviar for that fish.”

Miller hopes to have Yakama Nation caviar in more restaurants and boutique wineries by spring 2020. “It’s not just a luxury item — our [caviar] actually has a story behind it about the work that we’re doing on the restoration side,” said Miller. “That’s what we’re really trying to focus on to connect with those special customers that are conscious of those types of things.”

Robust caviar sales could also benefit Yakama trout, salmon, and lamprey restoration work.

“If we could get this project generating revenue, we could put it back into the program to expand our resources,” said Miller.

But until production ramps up, Crafted will continue to be the only restaurant in America serving and selling the sustainably raised 1- and 2-ounce jars of Yakama Nation caviar. Koommoo is certain his restaurant won’t be alone for long.

“The white sturgeon caviar that they’re producing … can rival any of the best caviars out there,” Koommoo said. “You’d have to be pompous to think otherwise.”