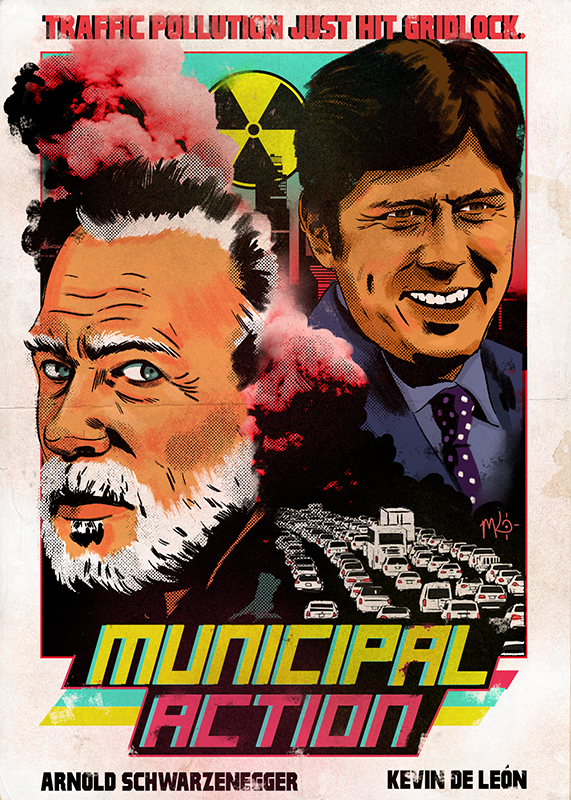

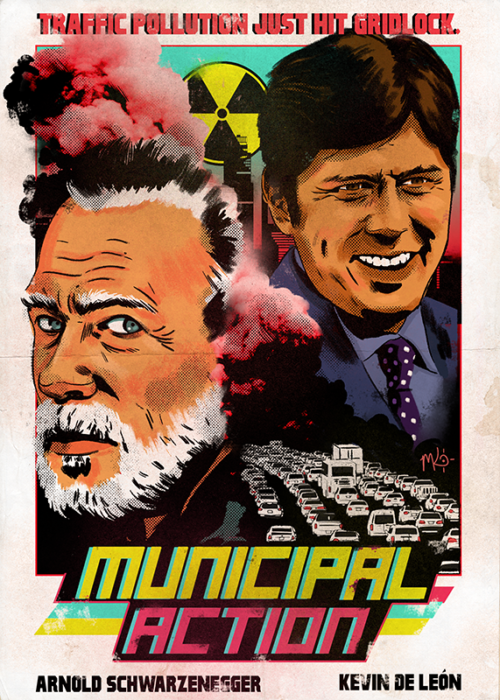

At first glance, they seemed to be strange bedfellows. So when Arnold Schwarzenegger, California’s former Republican governor, teamed up earlier this year with former state senator and Democrat Kevin de León to combat traffic pollution, the union garnered plenty of attention. Some called it clever strategizing by de León, the former state Senate president who is running for a Los Angeles City Council seat in 2020 (he lost a bid to unseat Senator Dianne Feinstein last year); others saw it as an attempt to bridge the partisan gap. The partnership, though, is emblematic of a major shift in the political landscape: state and local politicians targeting climate change in the absence of federal action.

De León, who describes himself as a “proud progressive,” already had a pedigree of climate legislation. As a state senator, he authored the 2018 bill that mandates California purchase all of its electricity from carbon-free sources by 2045, a measure that preceded a similar slate of clean-power bills in Western states this year. During his tenure, he successfully passed legislation in support of clean air, renewable energy, and parks and public lands.

In a joint May 4 editorial that appeared in the Sacramento Bee, de León and Schwarzenegger said they intend to find a bipartisan solution to one of California’s pressing environmental issues. “We have teamed up with researchers at UCLA and USC to develop solutions to transportation pollution, which is the leading source of unhealthy air and climate pollution in our state,” they wrote.

California policies, particularly environmental regulations, have been in President Donald Trump’s crosshairs. In September, for example, the Trump administration revoked California’s authority to set its own standards for vehicle emissions, to which 13 other states adhere. In response to the executive branch’s hostility toward climate policies and Congress’ inaction on that front, mayors and other politicians across the region are doubling down on local solutions.

“Here in California, we learned long ago not to wait for Washington to lead the way on environmental justice or battling climate change, and instead positioned ourselves as an example for the rest of the country,” de León said in a statement.

Salt Lake City Mayor Jackie Biskupski can pinpoint the moment climate action began to shift to a more local level: June 1, 2017, when Trump announced his intention to pull the United States out of the Paris climate agreement. After Trump made his announcement, Biskupski and her colleagues at the United States Conference of Mayors declared their strong opposition to the withdrawal.

“It didn’t matter whether you were a Democrat or a Republican, independent, or whatever. All the mayors came together, and we created a resolution saying to the world that the mayors will take this on. We do our part,” Biskupski said. “So that’s where sitting back and waiting for the federal government to do their part for the world ended.”

Biskupski was in a position to lead. A year earlier, she brokered a deal with Rocky Mountain Power, the local utility, to shift the city’s energy to 100 percent renewable sources by 2030.

According to James Fallows, a writer for The Atlantic who visited small and midsize towns across the country reporting his book Our Towns, local governments are a natural fit for action on issues like climate change. “At the city and regional level, there is much less ideological resistance to the need to address climate and sustainability issues, and much more awareness that green energy solutions represent an economic plus for a region rather than a handicap,” he said.

Take Fort Collins, Colorado. The city holds nonpartisan municipal elections, and is overseen by an unelected city manager who can remain on staff while council members and mayors change. Mayor Wade Troxell believes this form of government allows the city to focus less on partisan politics and more on long-term projects. One such program such as loans to finance energy efficiency improvements for homes and rental properties in low-income areas. The program earned the city a $1 million prize from the Bloomberg Philanthropies U.S. Mayors Challenge.

To Troxell, the gradual shift of power from nation to city seems to be an organic process. “You’re talking with neighbors and people throughout your community all the time. So there’s this really direct government that acts at that municipal level,” he said. “And with that, you know the pulse of your community.”

Some of these local and regional measures are being met with resistance at the federal level, igniting a showdown of sorts. After the Trump administration attempted to curtail California’s tougher emission standards, a coalition of more than 20 states filed suit. And four major automakers — Ford, BMW, Honda, and Volkswagen — signed on to California’s standards regardless.

Local activity on climate measures isn’t just in response to the executive branch. A paralyzed Congress, too, means municipal and state governments are left to take action.

Local and regional government, Fallows said, “is where the leverage is. That is where progress and cooperation seem possible. That is where the long-term view, and a fact-based perspective, and reasonable accommodation of varying interests, seems possible — and it is where experimentation is underway.”

De León remains devoted to addressing climate change at the local level.

“Until the White House is occupied by someone interested in leading humanity out of this existential crisis,” he said, “we will continue organizing in our communities to call for action at every level of government.”