On a cooling September night at Grand Canyon National Park, ranger Rader Lane sat cross-legged in an empty parking lot aiming a green laser pointer at the sky. A crowd of blanketed onlookers huddled around him. They were attending an astronomy program that is one of a handful organized by the park annually.

“A lot of us don’t realize it, but 80 percent of people living in North America today cannot see the Milky Way from their homes,” Lane, one of the park’s dark-sky specialists, told the audience.

Above us that night, the sky was a black sheet peppered with what felt like thousands of tiny stars. Peeking out from a line of skinny pines was the galaxy in question. The Milky Way looked like steam spewing from a teapot — a swirl of subtle orange, yellow, and white weaving a path vertically along the curved sky.

Lane went on: “Excess light is shooting up into the atmosphere from our buildings and cities, creating light domes that block our view of everything going on above.”

Earlier this year, the Grand Canyon joined a growing list of sites where visitors can expect an unobstructed view of the celestial. The Tucson-based International Dark Sky Association, or IDA, in June named Grand Canyon one of its 76 International Dark Sky Parks. If the IDA’s designations are any indication, the desert Southwest is the nation’s night-sky epicenter.

“Kind of looming over Capricorn here, we’ve got another, very dim constellation,” Lane said, the laser pointer tracing the sky. “That’s Aquarius the Water Bearer. Have you heard the song? This is the dawning of the age of Aquarius…”

Lane’s audience chuckled as he hummed the 1969 tune. But the song, he explained, references an important astronomical phenomenon. Six thousand years ago, sunrise aligned with the Aries constellation during the spring equinox. Today, it appears in Pisces. That’s because the Earth’s axis has been in a slow, gravity-induced rotation for nearly 26,000 years.

Long before the advent of electricity, humans used the stars to navigate, understand changing seasons, decipher the physics of the planet, and propose stories for our existence and place in the world. But the thread connecting us to the cosmos is fraying as cities grow and artificial lighting becomes increasingly present in our daily lives.

Darkness as a resource is an idea with deep roots in Arizona. Astronomy and space science research pumps about $250 million into the state economy each year, according to a 2008 study by the Arizona Arts, Sciences and Technology Academy. The IDA was founded in 1988 with hopes of ensuring a dark night sky for future generations. Its International Dark Sky Places program was created in 2001 and outlined best practices for low-impact lighting. Flagstaff, a city south of the Grand Canyon where astronomer Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto in 1930, was named the first International Dark Sky Community in 2001.

The organization has identified more than 120 dark-sky sites around the world. Those include a number of locations throughout the West, like Utah’s Rainbow Bridge National Monument, New Mexico’s Cosmic Campground, California’s Joshua Tree National Park, a chunk of central Idaho, and a smattering of cities.

The Grand Canyon has long been a stargazing destination. Hundreds of enthusiasts and scientists gather to view constellations with high-powered telescopes during the park’s annual Grand Canyon Star Party. Smaller viewing events, like the one Lane led in September, happen throughout the year. In 2016, the park sought to ramp up programming even more by seeking an IDA certification.

Now it’s the largest Dark Sky Park in the world, but the 1,900 square-mile complex in northern Arizona also resembles a small city. In addition to a motley collection of hotels, restaurants, and historic buildings, Grand Canyon Village includes lodging and school facilities for a few thousand National Park Service and vendor employees who live on-site with their families. About 6 million visitors come every year.

Parks hoping to gain dark sky status must organize educational programming about darkness conservation. A majority of the area also must comply with IDA guidelines by using low-wattage or warm-light bulbs, hoods that keep light from leaking skyward, and eliminating unneeded fixtures.

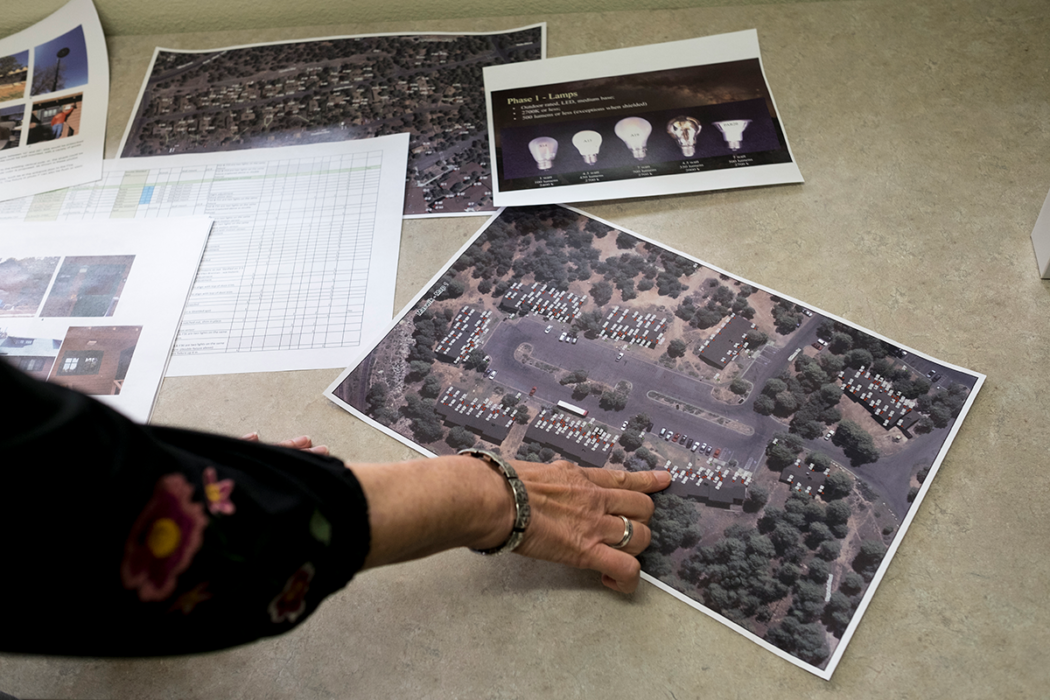

In 2016, Vicky Stinson, pictured above, is a landscape architect who has spent 16 years as a project manager for Grand Canyon National Park and almost three decades with the National Park Service. She was tasked with bringing 67 percent of some 5,000 light fixtures sprawled across the park to Dark Sky compliance.

“We already had an inventory of all the lights in the park,” Stinson said. “Our goal was to ensure each new lamp glowed a warm white or amber to be low-impact, so the bulb type is very important.”

Other factors were also at play. Stinson said architecture in the South Rim and Grand Canyon Village is defined by three eras — pre-1956, between 1957 and 1972, and after 1973. Each required certain specifications to ensure the new lighting still worked alongside existing structures.

“It was important to remember that new lighting was not about making some sort of architectural statement, it was about making sure the changes we were making fit with their surroundings,” Stinson said.

By June, she had retrofitted about 1,700 individual lights to painstaking customization. She estimates the entire operation cost the park around $350,000, almost all of which was funded by the Grand Canyon Conservancy. The next phase of the project will focus on lighting on the North Rim and the remaining fixtures in the Grand Canyon Village.

Humans have been trying to decipher the night sky since the beginning of civilization. But even as our knowledge base expands, Lane argues our comprehension is shrinking when it comes to this part of the natural world.

“It’s this crazy paradox,” Lane said. “At no other time in history have we humans been so informed about the science and history of the night sky. And yet, we have never been so disconnected from it as we are today.”

From the air we breathe to the water we drink, pollution is an inevitable part of modern life. Light pollution is no different. A 2011 study in the Journal of Applied Physiology suggested the blue lights from phones and computer screens can disrupt human sleep cycles by depleting melatonin levels. Hailed as low-cost and high-efficiency, bright LED lights are becoming increasingly popular in outdoor urban night lighting. Studies have shown that artificial light humans blast into the sky can have adverse effects on the feeding and reproduction of plants and animals.

Adam Dalton, International Dark Sky Places program manager at the IDA, said few people realize the effects of light pollution.

“When I tell people what I do for a living, usually their first reaction is, ‘Wait, light pollution, what is that?’” Dalton said. “Experiencing a less-polluted night sky for yourself is so much more powerful than my explaining — especially in a place as iconic as the Grand Canyon, because it’s far from the reality that most people live in.”

At the Grand Canyon parking lot where Lane was presenting last month, the painted white lines of asphalt under our feet were barely visible — at first, not much was. Some visitors fidgeted with phones in their pockets, using the muffled light to guide their path. Others wondered, out loud, how a park housing one of the Seven Wonders of the World hadn’t managed to get some decent night lights.

But after a while, the blue glow of screens cut out and the crowd quieted. The only light was a dim red hue from a glow stick circling Lane’s hat. The sky above us came alive.

Lane reminded the crowd that these stars, in this place, are the same ones that the ancestors of today’s Arizona tribes once used to help make sense of their lives. Civilizations around the world have created stories around these same constellations.

Staring at the unadulterated night sky is part of humanity, he said. Ensuring its continued existence is something we are all responsible for.

“Being subsumed by natural darkness is a part of our biology, and dark skies have health benefits both for our planet and ourselves,” he said. “I urge you to go back to your own communities and find out how to make sure more people can see the clear night sky — if we work together, one day instead of dark sky cities, we’ll have a dark sky planet.”