On August 8, Christopher Swain swam the length of Redfish Lake, trailed by a boat full of citizen scientists. The water in the 4.5-mile-long pool in Idaho’s Sawtooth Mountains was so clean it glowed, diaphanous curtains of minerals catching the light the way the sunlight streaks through deep ocean. “If you watch somebody unfurl a bolt of silk in slow motion,” he said, “it’s those colors.”

Swain draws public attention to threatened rivers and waterways by swimming them, and the dip in Redfish Lake launched his latest project, dubbed Boise River: Source to Snake, a monthlong exploration of the river from its headwaters in the Sawtooth Mountains to its confluence with the Snake River in southwest Idaho. During the journey of more than 100 miles, a group of educators and citizen scientists traveling with Swain conducted a battery of tests to assess the health of the river. The data track changes in water quality as the river courses through cities, farmland, and industrial sites.

“The Boise River tells the stories of so many rivers in the West,” said Heather Dermott, executive director of Idaho Business for the Outdoors, a nonpartisan group that sponsored the project. It irrigates fields of potatoes and wheat. It turns the turbines of hydroelectric dams, powering homes and businesses. It yields sport for catch-and-release anglers and food for catch-and-keep fishers. It pools in reservoirs where boaters gather and ferries people floating on inner tubes through the heart of Idaho’s capital. It is the source of 30 percent of Boise’s drinking water. All of these things affect the river’s water; the point of the project was to gather data that might reflect how and where.

With the results in, Dermott said, there’s a clear trend: “The farther you move from the high mountain source, the more disturbance you see.”

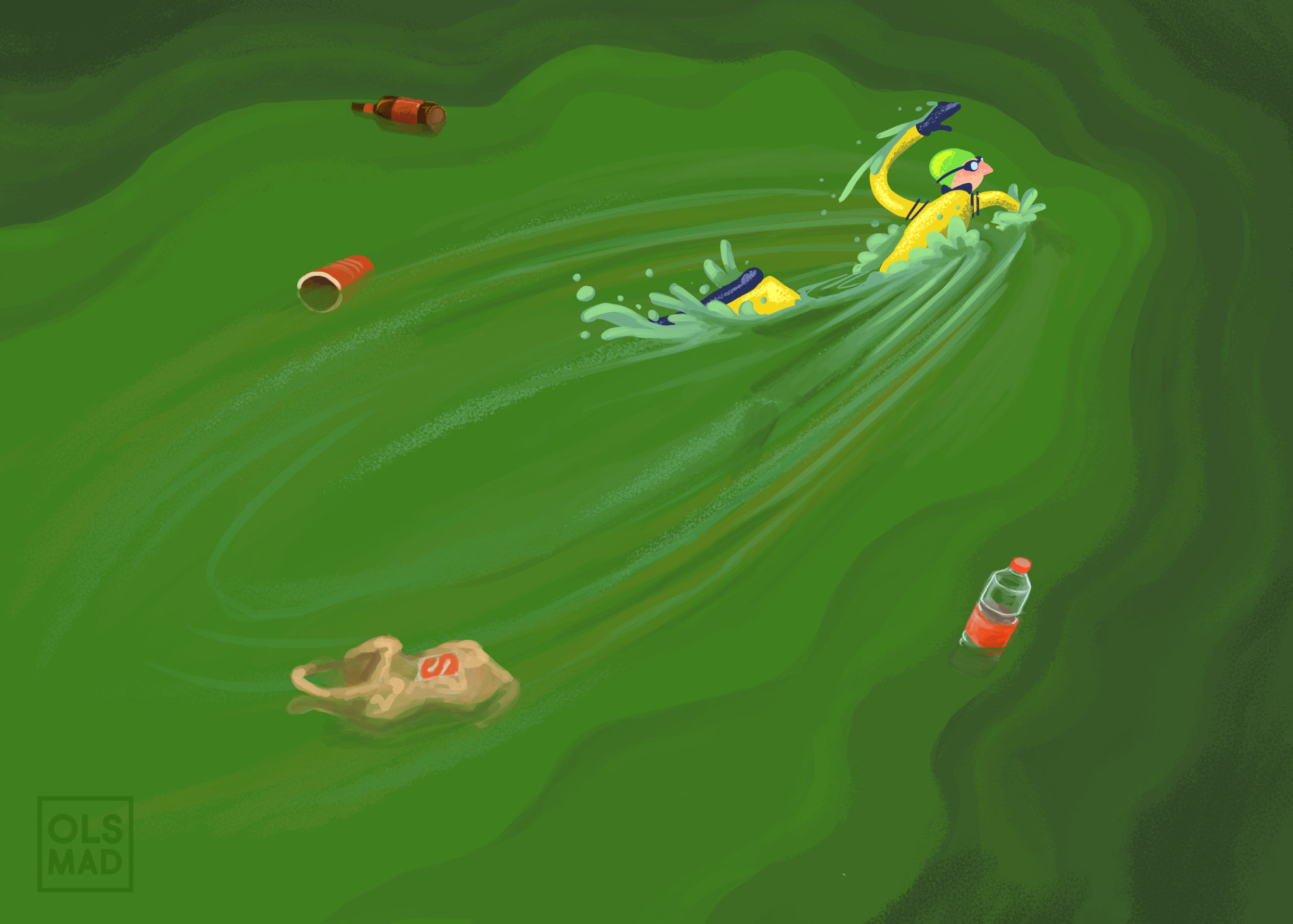

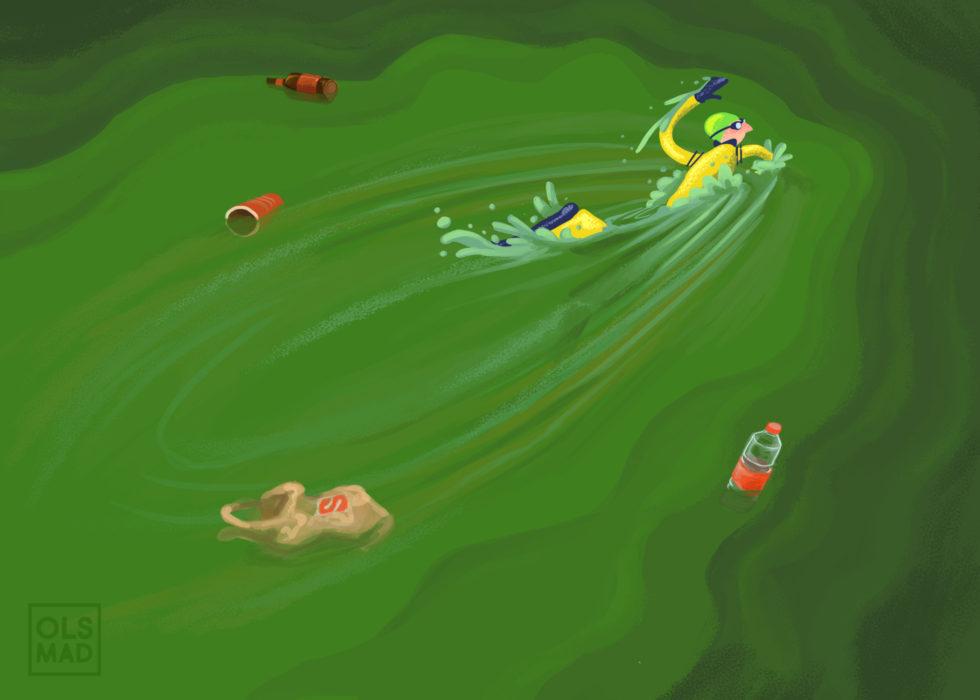

Swain has swum the entire length of rivers across the continent, from New York’s Hudson River to the 1,243-mile Columbia. Not all that water is as glorious as Redfish Lake. Swain has immersed himself in water laced with pesticides, sewage, and toxic blue-green algae. He has swum past nuclear facilities known to leach radiation into the water.

“When I get in there, it energizes the cleanup,” Swain said. “Media attention can change where something is on the priority list. If you shine a light, you can move something up the list.”

After the ceremonial splashdown in Redfish Lake, Swain and a team of volunteers loaded gear onto horses for a two-day trek to Spangle Lake, the headwaters of the Boise River that sits at 8,585 feet in the Sawtooth Wilderness. There, Swain and five volunteers gathered samples, measured the water temperature (61 degrees) and — without wetsuits — jumped in.

Spangle Lake sends a trickle of water southwest toward the tiny town of Atlanta. The backcountry trail here was too rugged even for horses, so Swain and the team continued on foot. They walked beside the trickle for two days with 50-pound packs, watching it grow into the Middle Fork of the Boise River. “Where we started, the river was only a body-length wide,” said Melissa O’Berto, who joined Swain’s team after graduating from the College of Idaho with a biology degree. “About 12 miles later, it was as wide as five people are tall.”

Where the Middle Fork merges with the North Fork, around 44 miles by car from Boise, the water grew deep enough to swim. Swain pulled on a wetsuit with a hood, neoprene booties and gloves, and committed to staying wet until he entered the Snake River 102 river miles downstream. “If there isn’t enough water to swim — and there often isn’t — then I wade, or I hang off the back of a tube and kick over the rocks.”

As the river flowed closer to roads, Swain started meeting the people of Idaho. He talked to a man fishing neck-deep in the river, children splashing in the shallows, and a lone volunteer picking up trash. They all seemed to want the same thing: a river clean enough for doing the things they enjoy. “It’s hard to be against clean water,” Swain said.

At Discovery Park, where the river flows cold from Lucky Peak Reservoir, Swain paused to recall what brought him here. “Six years ago, here at Discovery Park, a group of high school students asked me if I’d ever consider swimming the Boise River,” he said in a video stream. “Here I am!”

Those students were in a class taught by Dick Jordan, an environmental science teacher at Timberline High School in Boise. Jordan, who grew up in rural Idaho, had a track record of developing outdoor education programs for kids. In 2013, he asked Swain to speak to his students. They were riveted by Swain’s testimony, and asked him if he’d come back to swim the Boise. If there was a platform, he said, he’d do it.

Six years later, Jordan, who retired from teaching in 2015, found sponsors for the Source to Snake expedition, and created an accompanying educational program. The project would connect Swain’s journey with more than 240 students from 12 Idaho schools. These students would learn — in hands-on workshops at river’s edge — how to perform water quality tests. Those tests would produce data used to compute the river’s water quality index, a standardized metric for evaluating water quality. As Swain made his way downriver, a rotating crew of volunteers, students, and citizen scientists at 15 locations collected water samples, which were then sent off for testing. (Certain tests were performed by professional labs, but most were done by students.)

“Nobody had that [data] from source to Snake,” Swain said. “If you have that, your ability to influence policy discussion is huge.”

The water quality data would, Jordan hoped, provide a snapshot of the health of the Boise River as the population of Idaho continues to grow. According to census estimates, Boise is among the 10 fastest-growing metros in the nation, and that growth means increasing water demand. “That’s why we need the baseline,” Jordan said. “It’s a point of reference.”

Water quality index factors in data from nine measurements — including temperature, pH, fecal coliform bacteria, and total nitrogen — to grade bodies of water on a scale from 1 to 100, with higher numbers indicating better overall quality.

“The beauty of the water quality index is, you get all this data, run it through a mathematical model, and get a single number,” said Bob Beckwith, a retired science teacher who oversaw the riverside workshops along Swain’s route. “As you go down the river, you see that number diminish.”

The water quality values ranged from 85 at Redfish Lake to 67 at Martin Landing, where the Boise River flows into the Snake River. The individual water quality tests revealed more nuanced trends.

“As we moved down the river, especially below Boise, we saw temperatures rising, more elevated phosphate, nitrate, and fecal coliform levels,” said IBO’s Dermott. She spelled out the implications: Elevated temperatures can be harmful to fish. Too much phosphate can encourage the growth of toxic blue-green algae. High levels of fecal coliform can indicate higher bacteria levels.

Though the trends were not completely linear, the general takeaway was this: the farther from the source, the lower the water quality.

“It went from mineral water to chocolate sludge,” Swain said.

It wasn’t the dirtiest water Swain has ever swum. (That honor belongs to Brooklyn’s Gowanus Canal, which he said smelled “like poop and oil and gasoline.”) It wasn’t his longest river. (That would be the Columbia, which he swam intermittently over the course of six months.) But the Boise had one trait that stuck with him: overwhelming local support for “fishable, swimmable, drinkable water,” from the people who rely on the river.

Swain and other members of his team said they expected some pushback for their environmentally oriented journey in this conservative state, but they were met with near-universal support. Swain asked folks he met to share their hopes for the river and use an app the team built (it’s called Boise River: Source to Snake) to record small actions people could take, from picking up dog waste to measuring water temperature.

His swim inspired educators. In Boise, seventh graders from Sage International School donned rubber boots and waded into the river to capture macroinvertebrates, which they examined as an indicator of biodiversity and river health. They were assigned a role — farmer, utility, home owner — and then discussed how water supply should be divvied up. They toured the Marden Drinking Water Plant to learn how water from the river is cleaned and re-used.

“Overall, this day was an incredible success, and has created a model which can be replicated for our seventh graders for years to come,” said Bryce Mercer, a science teacher at Sage.

The swim concluded in late August, but Swain said there’s work still to be done. “We’ve done the science,” he said. “Now we have a baseline to figure out what we want to do.” His take on next steps: “You figure out the pristine areas, and move to protect those right away. Once they get wrecked, you can’t walk it back. Then you go to work on restoring parts that are actively in need of cleanup,” he said. “This takes hard work and will. Those are two things that are in abundant supply. No one’s going to out-work the Idahoans.”