One letter changed Camila Coddou’s life. In January, Coddou started receiving messages from her former coworkers at the Portland coffee company Ristretto Roasters. They were appalled at posts on co-owner Nancy Rommelmann’s newly launched YouTube channel, #MeNeither, which cast doubt on the wave of #MeToo posts sweeping social media. Among Rommelmann’s videos was one questioning the validity and motives of Asia Argento and Rose McGowan, two of the many actresses who accused Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein of sexual harassment and assault.

“We had women on staff, queers on staff, survivors on staff — that’s always going to be the case statistically speaking,” Coddou said. “These people who viewed this person as their boss were now watching videos of her essentially denying stories of survivors.”

Coddou, who is petite with long salt-and-pepper hair, was the operations manager at Ristretto for three years. She had left the company two months prior, citing a relationship with the owners that had soured. (Ristretto Roasters did not respond to a request for comment.) Her position, a nexus between staff and the owners, was never filled, Coddou said, leaving an institutional vacuum. So her former coworkers looked to her for support.

After many of them expressed dismay with Rommelmann’s videos, Coddou sent a letter, signed by 30 current and former Ristretto employees, to news outlets across the Portland area, detailing Rommelmann’s YouTube series and involvement with the coffee company, and denouncing the content of the videos.

“We believe it is a business owner’s responsibility to create a safe and supportive working environment for their employees,” the letter said. “Invalidating assault survivors throws into question the safety of Ristretto Roasters as a workplace and has the potential to create a demoralizing and hostile environment for employees and customers alike. This cannot be tolerated.”

Sending that letter immediately threw Coddou into the spotlight, essentially making her the de facto voice of workplace equity and responsibility in the Portland coffee world. She embraced the opportunity to speak to the ethical issues she had witnessed during more than a dozen years in the industry.

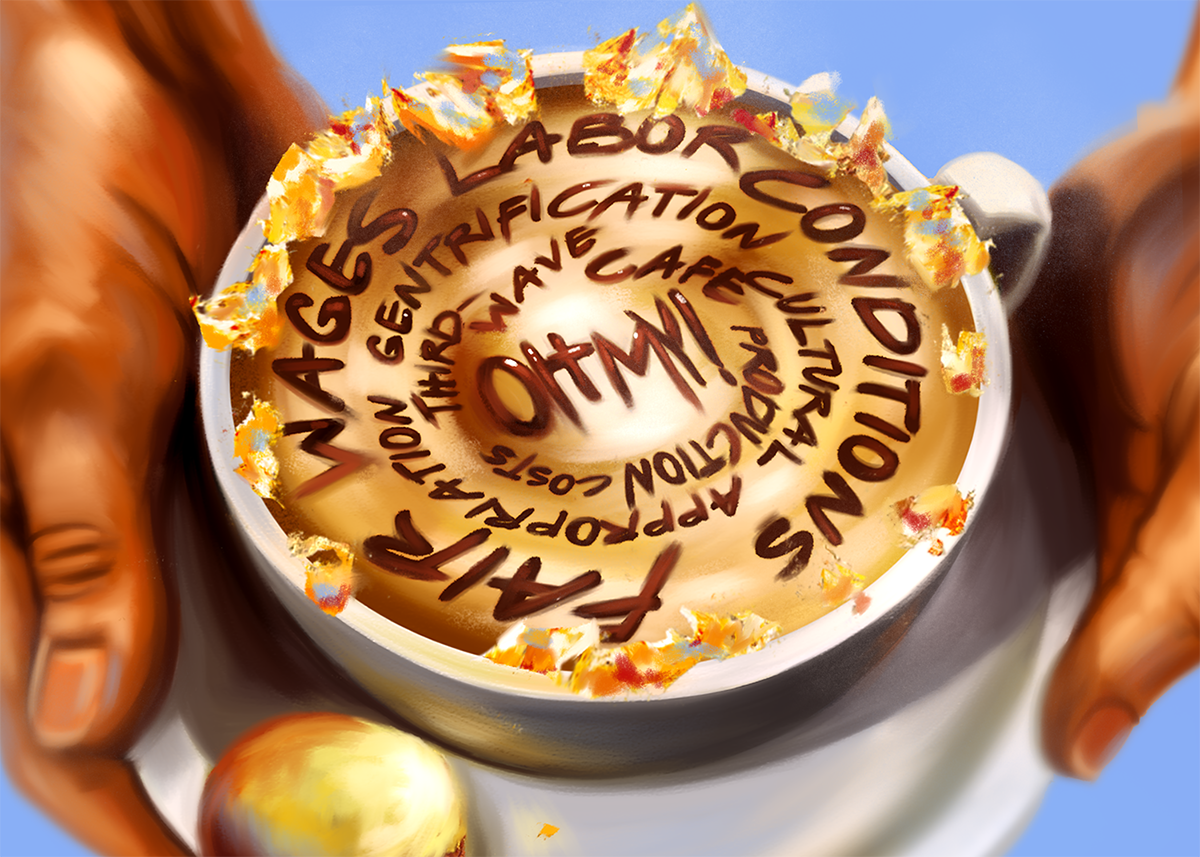

As the fight for livable wages and access to benefits breaks out in big cities across the country, the world of coffee had remained surprisingly void of those conversations, until recently. In the past year, Coddou’s experience with employees at Ristretto was just one of many to come to light regarding the coffee industry’s complex relationship with issues of representation, fair pay and treatment of baristas, and the shops’ role as harbingers of gentrification.

Allegations of sexual assault and harassment, late and missing paychecks, and cringe-worthy marketing have spawned a grassroots movement within the coffee community. Coddou believes these employees will lead the charge toward changing the industry for the better. She also hopes to play a part in this movement.

In many ways, coffee is America’s great unifier — you can find a cup of joe everywhere from rural Montana to a booming metropolis like San Francisco. But in many Western cities, certain types of cafes — often called “third-wave” coffee shops by those in the industry — are becoming ubiquitous. You know the type: specialty roasted beans, intricately beautiful latte art, walls lined with white subway tile, and often steep prices. These shops seem to sprout on the corner of every neighborhood just as it’s beginning to gentrify — a phenomenon researchers are beginning to notice, too.

As early as 2001, Australian geographers showed that fancy coffee shops — ones unaffiliated with big brands, and often sporting Italian names — correlated with gentrification in Sydney. In 2015, researchers with the Seattle-based real estate firm Zillow found that properties near Starbucks locations appreciate faster than other homes in the neighborhood. (Coffee insiders would note that Starbucks is actually a second-wave coffee establishment.) And when sociologists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst wanted to compare gentrification with crime rates in Chicago, they used coffee shops themselves as a marker of the phenomenon, arguing a fancy cafe says more about gentrification than median income data.

“Coffee shops provide an on-the-ground and visible manifestation of a particular form of gentrification — the increased presence of an amenity often associated with gentrifiers’ lifestyles,” the authors wrote. “Furthermore, this measure also captures the role of corporate and private actors (i.e., coffee shop properties) in the gentrification processes.”

Now, some in the industry are saying it’s time to inspect this third wave a little more closely, especially when it comes to ethical issues. In 2018, the founder of San Francisco’s Four Barrel Coffee was forced out following a lawsuit alleging a culture of sexual assault and harassment. A year earlier, Denver’s ink! Coffee sparked widespread backlash when a sandwich board out front boasted it had been “happily gentrifying the neighborhood since 2014.” Locals responded by smashing a window and tagging the storefront with graffiti.

In June, workers at the flagship branch of Seattle’s Slate Coffee walked out in protest of late paychecks and what they said was a toxic work environment. The owner told The Seattle Times that at least nine workers quit.

There are implications for those who speak out. After Coddou sent her letter to Portland media outlets and fielded dozens of interviews, the attention led to online trolling and harassment. Even Ristretto lashed out; A since-deleted tweet on the company Twitter page read: “Camila! The little lady grinding her ax.”

Coddou didn’t stand idly by. She decided, instead, to travel the country, connecting with baristas all over, and launched Barista Behind the Bar, a website filled with interviews that shine a light on issues in the industry. The on-the-ground insights from baristas will inform an equitable hiring curriculum Coddou hopes to produce.

The coffee industry intersects with a multitude of sociocultural conundrums. Within each shop, there are questions about workplace conditions and labor practices. Everyone from the barista to the coffee farmer to the neighborhood’s residents might get shortchanged.

Coddou, who has both been a barista and hired baristas, believes the folks prepping espresso have valuable insight about these coffee contradictions. For instance, baristas — like many service-industry professionals — are often compensated like novices even if they have years of experience.

“The experience of the barista has always been paramount,” Coddou said. “People in ‘entry-level positions’ are hardly ever entry-level. If they’re good enough to stay in the industry … they have incredible insights that people aren’t even tapping into, to their detriment.”

Coddou has already conducted more than 20 interviews between Portland and Seattle for Barista Behind the Bar. The conversations cover topics including inclusivity, empowerment, accountability, and the accessibility of industry information.

What she’s heard is already feeding her insight to potential solutions. “People have thoughts on equity, thoughts on how to diversify, what kind of communication they need, how to save money — basically how to create more sustainable work environments where they’re happy and it’s more financially stable for the employer,” Coddou said.

Her work is inspiring others. Coffee at Large, an in-progress nonprofit born from the Slate Coffee walkout, recently organized to shine a light on workplace injustices in the coffee industry, particularly for employees working in at-will states, said the group’s executive administrator, Samantha Capell. The organization hopes to provide baristas with information about organizing — unions, Capell said, don’t work with such a transitory community — as well as teaching owners and managers how to treat employees.

“Unfairness is unnecessary and unhelpful to the coffee industry, and can be adjusted very easily,” Capell, a former manager at Slate, said. “We want to teach workers and management that they can work together and it doesn’t have to be too difficult. We can keep elevating the industry instead of moving towards automation because the current model isn’t working.”

The group is in the process of attaining 501(c)(3) status, and is collaborating with Coddou on her code of ethics.

Coffee shops and their relationship to gentrification is particularly visible in Portland, where new cafes seemingly open every month. Coddou thinks cafe owners can open more ethical shops by thinking big-picture about the relationships involved in a cafe.

“If your intention is just to make money at the expense of everyone around you, I don’t think that’s a sustainable working model,” Coddou said. “The cafe as an entity has always been a community space … are you dropping into a community of people that don’t look like you who are losing their rights?”

Angel Medina, who owns Portland’s Kiosko cafe, hopes to connect the coffee he serves not just to an often overlooked consumer community, but more closely to coffee producers. Medina is frustrated by the disconnect between coffee’s origins as an agricultural commodity that supports farmers in many third-world countries and the arrogance of those making and selling it in Portland. He often hears people in the Portland coffee scene discussing hot-button issues, but to Medina, they’re often empty words.

“With all the conversations that are happening, from the cost of coffee, traceability, and everyday issues like the lack of minority representation, these are all things that everybody is supposedly behind,” Medina said. “But you just don’t see it.”

In 2017, Medina opened his first coffee shop, a closet-sized cafe serving drinks made from beans he roasts himself. The menu — for a time, listed only in Spanish — includes cafe de olla, the warmly spiced Mexican “pot coffee” with cinnamon and piloncillo, and ahogados, the Mexican version of affogato with ice cream from a local neveria. The warm waterfront cafe, with its dark wood and strewn-about copies of the Sunday New York Times, stands in contrast to Portland’s stark white, subway-tile-lined shops. Within six months of opening, two more locations were already in the works.

Medina said few cafe owners embody the ethos that he’s looking to realize: for starters, hiring more people of color. In addition to a diverse staff, Medina focuses more on his product’s origins than just what is trendy at the moment. Rather than focusing on high-end espresso machines and fancy latte art, Medina’s interest centers on the coffee itself.

He’s taken numerous trips to Mexico since opening Kiosko, meeting with farmers and making connections in the coffee industry there. In the coming months, he’s planning to relocate to Mexico to continue working with local farms and finding rare, high-quality coffee beans while still supplying his own cafes. In the process, he hopes to boost Mexico’s reputation within the third-wave coffee world.

Though many of the hundreds of shops in Portland either roast their own or sell various beans from across the world, they’re all buying from the same handful of distributors, he said.

“The last trip I took [to Mexico] was incredible,” Medina said. “I found stuff that was really rare that other importers couldn’t find … because of my connection to the people there and being Mexican American and speaking Spanish, I was able to have an advantage over an importer coming in.”

He wants to use that advantage to get more distributors into Mexico to find these unique producers.

Medina hopes that by seeking out the untapped coffee farms, he’ll be able to help push the needle beyond the cliché of what people think of as Mexican coffee, with its chocolate, nutty, and dried fruit notes.

“When you’re at origin, you can see an entire operation,” Medina said. “You can see their own traceability within the farm, see where seeds are coming from, how they’re grown, what they use to produce coffee.”

Another Portland cafe owner is focusing on ethics at the farm level, too. Mike Nelson first learned that the price coffee farmers make per pound often doesn’t even cover their production costs five years ago, while a graduate student at Florida State University. He refocused his research to center around the cost of coffee production, then left school altogether to move back to Portland with his spouse, Caryn, to grow their own roasting business.

In 2017, the Nelsons opened their airy, two-story cafe, Guilder, in Northeast Portland, where they sold their Junior’s Roasted Coffee label. To source beans, they sought a farm with which they could work directly to cover the cost of coffee production from end to end.

Though the price of one coffee in Portland regularly reaches $4 or $5 — specialty milks, roasts or other additions aside — the product itself is still traded on commodity markets alongside goods like grain, beef, and oil. And the commodity price for coffee has been so low in recent years that farms are going bankrupt, and presidents of coffee-growing nations are planning to ask roasters to pay more at the upcoming UN General Assembly.

Even though coffee beans are trading for about $1 per pound on the commodities market, Nelson decided to pay the farm his company sources from $4 per pound — a 75-cent premium over what their importer was paying — to ensure the farm was covering its costs.

Even now, two years into the project, Junior’s sells just one of their roasts at a price that fully covers the cost of production. The Nelsons want their entire line of beans to cover production costs, and are currently in talks with several more farms, from Brazil to Burundi, that are interested in collaborating on this project. But they know that for that kind of change to be palatable — in the form of higher prices at the cafe — they’ll need to educate their customer base.

The Nelsons have taken an obsessive, multilayered approach to get customers and buyers to think about how much it actually costs to grow coffee. The cafe’s wifi password is “askmeaboutcostofproduction”, and they sell a comic book about coffee economics in the store. A quick synopsis about what it actually costs a farm to produce each specific coffee, how much the Nelsons paid for it, and their sourcing logic is printed on every bag of Junior’s coffee.

Nelson hopes to inspire other cafes to do the same, because it will take more than just their one company paying increased prices to make a difference. One farm the Nelsons had started working with is going out of business this year. While the Nelsons have bought 25 bags of coffee from them, that farm produces anywhere from 200 to 300 bags annually.

“If everyone was buying coffee at those prices, the farm would be in a very different place,” said Nelson.

Just like Medina, the Nelsons believe being fair at every step of the coffee making and selling process, including at the product’s source, is just as important as being fair about their own workers’ wages and conditions.

After all, Coddou said, when it comes to an industry as complex as coffee is, all of these interconnected issues require change. “We need to figure out how we source responsibly, how we employ responsibly, and how we’re responsible to the communities we serve,” she said. “How that looks doesn’t really matter to me.”