“Two unwanted parties in an alley.” It was a cold February morning, more than a decade ago, when the call came in to Denver Police Reserve Officer Rob Parks and his partner. When the pair arrived at the downtown location, they found a broken-down car, a single mom, and two kids. The officers, concerned about the frigid temperature, drove the trio to a shelter so they could warm up.

“Beyond simply getting them in the front door and saying good luck, there just wasn’t a whole lot we could do to better serve them,” Parks said. “At the time, I had no idea the resources that were out there. There was so much siloed information within Denver.”

If that same call came in today, Parks said, the outcome would be different. He could access funds to have the vehicle repaired, or provide bus tickets. If needed, Parks could connect the mom to domestic-violence services. He is now well-versed in the city’s shelter system and service offerings, and knows what questions to ask when he comes across people in crisis. That’s because Parks is part of Denver Police Department’s Homeless Outreach Unit, a team of eight officers formed in 2007 that focuses on building relationships with — rather than arresting — people without housing.

Parks was one of the outreach unit’s first two officers, and his experience that February morning is one reason he signed on. “It’s just something that’s stuck with me through the years — that there had to be a better solution to many of the problems we dealt with on a daily basis,” he said. “It’s nice to be part of the solution.”

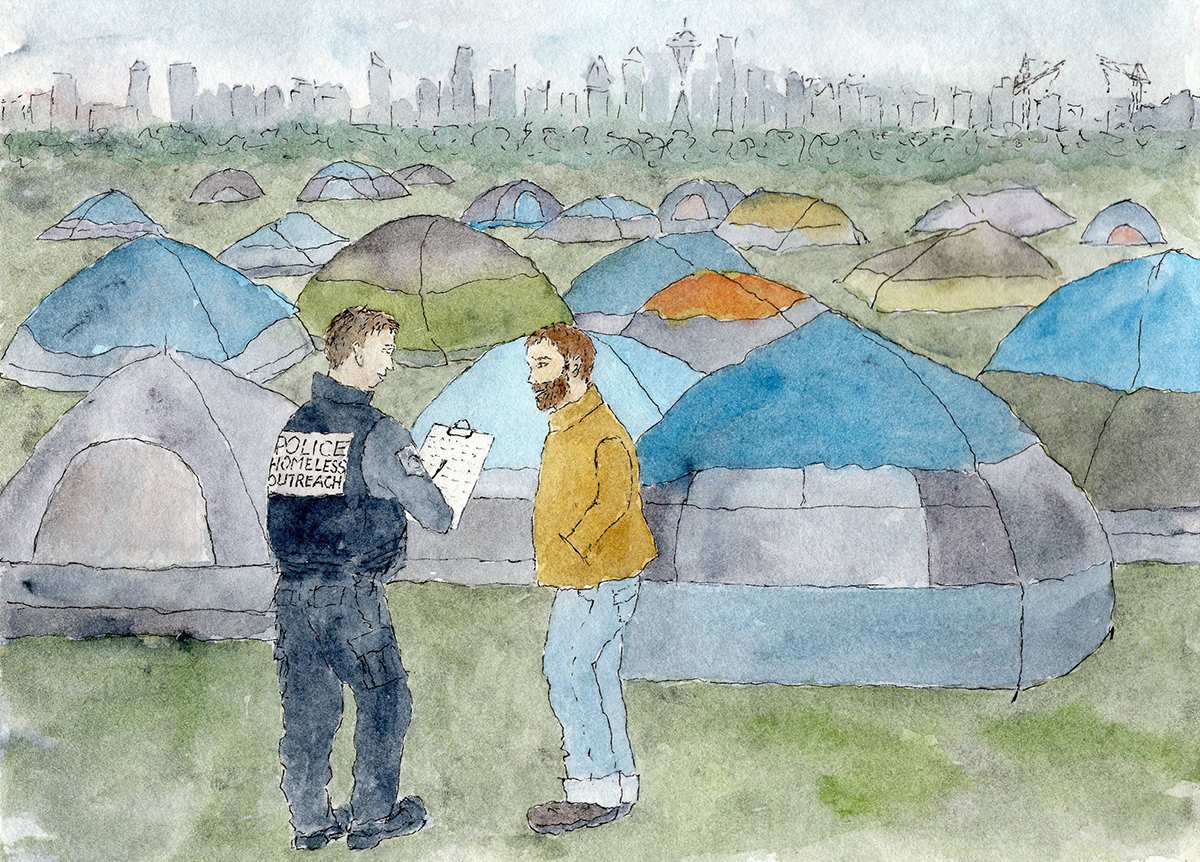

Homeless outreach teams can be found in police departments from Florida to California, though there’s no hard data on exactly how many exist. Each operates slightly differently, but the gist is the same: Specially trained or hand-picked police officers are tasked with linking unsheltered individuals — particularly the chronically homeless — with appropriate services and addressing unsafe encampments. Often, these teams operate in conjunction with social workers, outreach workers, and nonprofits serving the same population.

That’s not to say these officers never take people into custody, but they’re trained to talk rather than ticket when appropriate.

“Being homeless isn’t a crime,” said Chuck Wexler, executive director of the nonprofit Police Executive Research Forum (PERF). “Progressive police departments are recognizing they need to take a problem-solving approach.”

As much of the West faces an affordable housing crisis, these outreach crews have become vital components of cities’ overarching homelessness response plans. In the Seattle area, more than 12,000 individuals experienced homelessness last year — the third-largest homeless population in the country. In February 2017, the city launched its Navigation Team, a collaboration between the Seattle Police Department and outreach workers.

“Before the Navigation Team, we really didn’t have a centralized, coordinated effort,” said Will Lemke, spokesperson for the group. “The decentralized nature of it created a lot of points of friction and room for improvement.”

In the first quarter of 2019, the 38-member Navigation Team made contact with 731 individuals and were able to connect 222 with shelters. While that may sound miniscule compared with the total unsheltered population, those interactions equate to a 30 percent referral rate — a massive improvement over the city’s reported 3 to 5 percent referral rate before the Navigation Team’s formation.

San Francisco employs an even more robust command-center approach. Its Healthy Streets Operation Center (HSOC) launched in January 2018 as a coordinated effort between six city agencies and the police department. Around 70 police officers are dedicated to homeless outreach, with more than 30 directly assigned to HSOC. When calls come in, they’re triaged at HSOC headquarters, and then the appropriate responder is dispatched.

“It takes it off the plate of the other officers who are doing police work,” said Commander David Lazar, who runs the police department’s community engagement division, which includes HSOC.

Providing help to homeless individuals rather than arresting them represents an important transition for law enforcement. Civil infractions lead to legal troubles that can perpetuate homelessness. According to the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty, ordinances banning camping, panhandling, loitering and the like are ineffective, expensive to enforce, and “often violate homeless persons’ constitutional and human rights.”

This state of affairs complicates the situation for police officers. In Denver, for instance, outreach officers are tasked with linking folks with shelter and services, but they also must enforce a citywide camping ban. The same officers that do this outreach work are also in charge of disbanding encampments when they pose health and safety risks — taking away shelter from the very people they’re assigned to help.

Still, approaching these interactions from a position of assistance instead of hostility can go a long way. “An officer might be the first face that somebody who needs help is going to see,” said Chris Conner, a former outreach worker who’s now the director of Denver’s Road Home, the city division that facilitates the Mile High City’s homelessness response. “Those first engagements are really important. They’re going to be memorable, and they’ll be memorable for better or for worse.”

Some individuals remain resistant to interacting with the police. “It can take weeks or months or even years to build that rapport,” Parks, the Denver officer, said. Indeed, a 2018 PERF report said it often takes officers 15 to 20 contacts before an individual experiencing homelessness accepts help. Dedicating officers to work with these folks and actively turn conversations into service connections could speed up that process.

“The experience of homelessness, no matter what, is likely going to increase your number of contacts with enforcement, with the legal system,” Conner said. “It’s smart to have a team that’s designated and sensitive and services-forward within the Denver Police Department to help facilitate those contacts along.”

While many officers would like to see even more services available in their districts, the homeless outreach teams say they have enough available capacity to do their work. In Seattle, cops can’t clear an encampment unless shelter space is available for residents, and there are 17 open beds on an average night for the Navigation Team to refer people to. San Francisco has 15 beds set aside for HSOC. “We’re all trying to work to find the best ways to get people into shelter, into housing. Like any big city, we have that supply and demand issue as well,” Lazar said. “It is a challenge, and we need to continue to work on it.”

It’s clear that work needs to involve a slew of people across a variety of departments. “Cities want to get at: What are the underlying causes that made this person homeless — not just what is their condition today, but how did they get there?” Wexler said. “The police are the entry point … [but] you really have to ask yourself: Is the issue of homelessness really a police problem, or is it a community-wide problem?”