The last light was fading and first stars starting to appear as Troy Waters fired up his swather and drove it to his fields, its blades wider than the two-lane road he took to get there. He spent the night mowing rows of bluegrass, heaping the cuttings into piles he then left to sun-bake for days before returning with a combine to harvest the seed.

Waters farms in the Grand Valley on Colorado’s Western Slope, the fourth generation in his family to do so. The valley here formed in a geologic mosaic — tan creases of cliffs on one side, red sandstone canyons on another, and a 10,000-foot-tall blue mesa like a bank against the eastern horizon. Below, the Gunnison and Colorado rivers join, passing through the towns of Palisade, Grand Junction, and Fruita. Without that water, there would be no rows of alfalfa, wheat, grapevines, and peach trees in this valley — or any farms at all in the arid region. The Colorado River provides water for about 40 million people and irrigation for 5.5 million acres of farmland, according to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

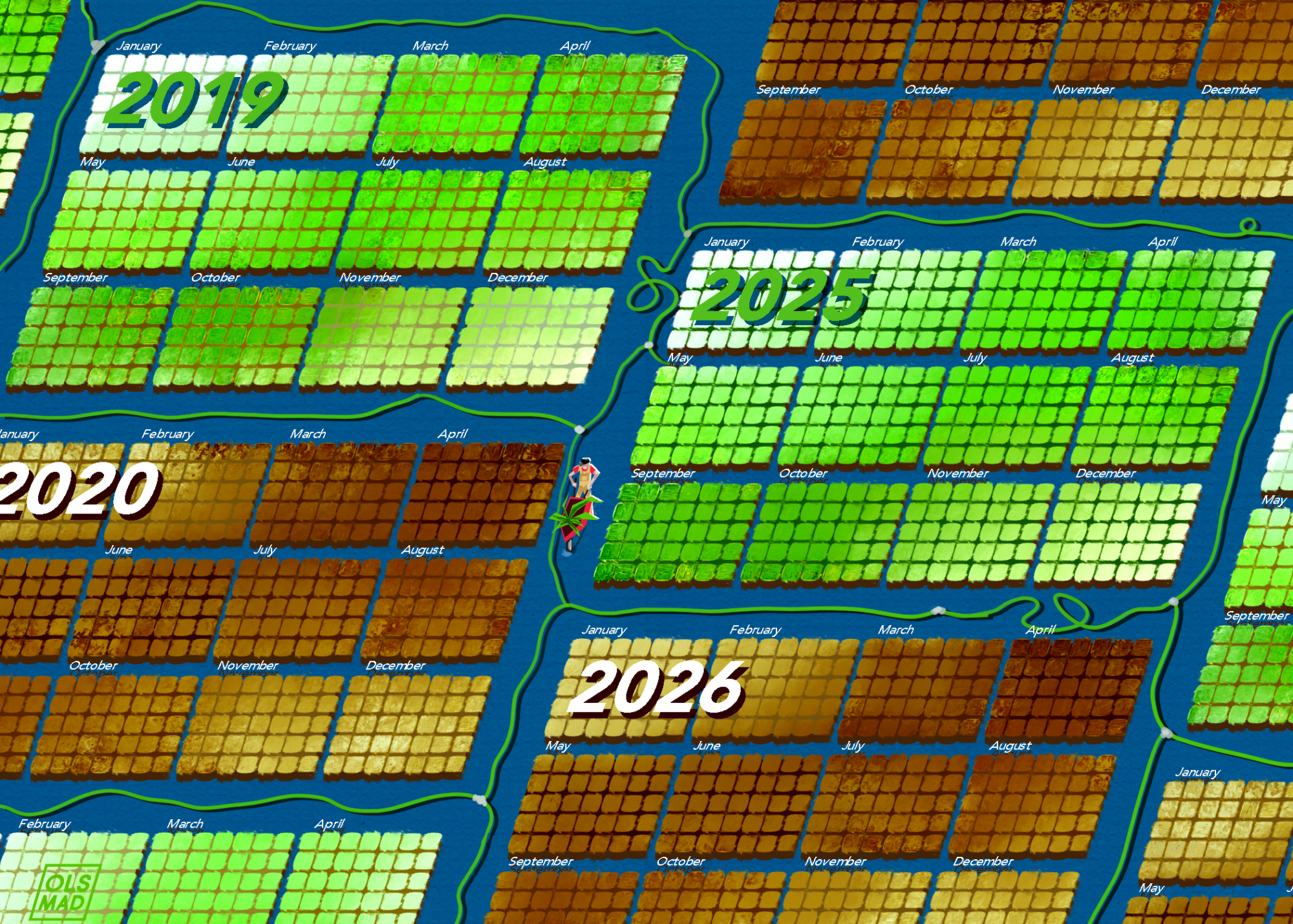

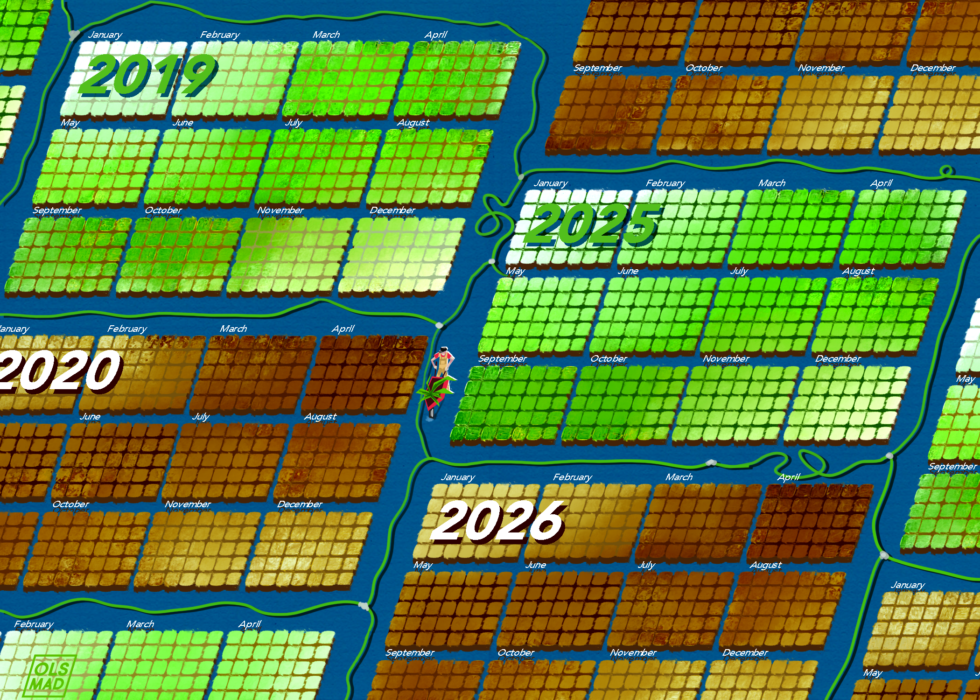

In the early 2000s, the reservoirs used to regulate its snowmelt-fed flows, lakes Powell and Mead, were nearly full. But extended dry conditions have drained them to levels not seen since the 1960s when Powell’s dam was just finished. At this rate, the reservoirs could reach critically low levels as early as 2021.

As agriculture draws the largest share of water in the West, farmers like Waters are suddenly in the crosshairs as water managers discuss how to handle the chronically over-taxed river.

That’s why, this season, Waters is watching six of his wheat fields to measure how quickly the crop sprouts, how thick it grows, and how much water it needs to do so. He’s monitoring the lingering effects of having participated in a pilot project that asked 16 farmers, himself included, to skip a season of planting on some of their fields. The two-year project run by the Grand Valley Water Users Association is testing ways to reduce water use. Waters, who serves on the association’s board, as well as the Ute Water Conservancy District and the Governor-appointed Colorado Water Quality Control Commission, says when the idea debuted, he was its most vocal opponent.

“It doesn’t make sense to me not to farm land that’s been farmed for generations,” he said. “My opinion on that has not changed. But I also think it’s a necessary evil.”

Colorado River water is divvied up according to a compact struck in 1922, but the previous decades had been unusually wet, and water managers overestimated the river’s annual flow. The second half of the 20th century saw the river’s flows short of their plans for it by as much as 2 million acre feet. Now, with even drier conditions, that gap is projected to widen.

Daniel Birch, who worked with the Colorado River Water Conservation District for nearly two decades before retiring last year, said the point of pilot projects like the one run in the Grand Valley is to test water users’ ability to adapt to that shrinking supply. “The driving concern was that, if the system is really at or beyond its capacity, what’s that going to mean? Who’s at risk?” he said.

Complicating matters, water law says if there isn’t enough water to go around, oldest rights take priority. But the newer claims on the Colorado River are largely for cities, namely municipalities on Colorado’s Front Range. “If you think agriculture is going to continue on its merry way while cities — Denver — is out of water, you’re crazy,” said Birch.

So the Grand Valley Water Users Association worked with The Nature Conservancy to launch the pilot program testing strategies for reducing water use on farms — before someone else mandates it. The group figures their proactive approach will also secure them a seat at the table in drought contingency planning and hopefully protect their agricultural way of life.

The project Waters participated in also drew funding from the System Conservation Pilot Program, a Colorado River Basin-wide effort to explore new ideas for compensating farmers for reduced use. The results were promising. In 2017, with 1,252 acres of alfalfa, corn, and winter wheat and 10 farmers enrolled, the association saved 3,178 acre feet of water.

“The whole concept is, we’ve got a water security crisis looming, and there’s a market-based concept to deal with that,” said Aaron Derwingson, the water projects director for The Nature Conservancy.

But the idea runs up against another traditional aspect of water law, which historically comes with a use-it-or-lose-it clause. Farmers were concerned about how they could not use their water one year and know it would be there for them the next.

“We heard that everywhere,” said Leon Szeptycki, executive director of Stanford’s Water in the West Program and lead author of a 2018 study that tracked these programs and how water laws are adjusting to ease their spread.

Colorado, for instance, has revised its statutes to permit temporary “environmental water rights transfers,” like and including the program that saw farmers in the Grand Valley fallowing fields. But despite the new laws, “this philosophy of water use is so entrenched that it’s sometimes hard to convince farmers that their water right is safe,” Szeptycki said.

That problem exists in several states in the area, too, where laws are in various states of allowing water transfer rights. “If these types of programs are going to have broader traction in the Colorado Basin, that’s an issue that’s going to need to be addressed,” said Szeptycki.

Those involved with the Grand Valley’s program are now assessing the results. They got a basic proof of concept, said Derwingson. Farmers are interested, but many also said they didn’t want to be the only ones involved. “[They told us], ‘We need to have participation from [agriculture] in other geographies and we need to have participation from other sectors,” he said. “Everybody needs to share the pie of pain.”

Birch also worries about scalability. The estimated 3,200 acre-feet of water saved in 2017 is a drop in the bucket of need calculated at 500,000 acre feet. But, he said, if any single community were to try to take on too much of the effort toward addressing that gap, and fallow too great a share of their farms, it could destabilize other economies around farming, like local seed and equipment suppliers. It’s safer to stock up water slowly, in small increments, but that means looking past this year’s abundant snowfall to realize the time to start is now.

“You really have to let that account build up,” said Birch.

Waters, for his part, wonders how much the program really saved water in the long run. When he planted a winter wheat crop on the 125 acres he fallowed last year, he said it took twice as much water to sprout.

His chief concern is that the program stays voluntary. There are logistics to sort out, too. Compliance with the program, which required he keep his fallow fields bare, even of weeds, necessitated repeat herbicide treatments. Between the time and money spent clearing the weeds and the payments for not watering, he estimates that with those acres, he just broke even. But, he said, that’s the way it should be. The program shouldn’t be more profitable than growing crops.

A survey of pilot program participants found that eight of 20 who responded thought the financial impact was a “significant benefit,” while 10 saw it as “marginal.” And while many of the farmers, like Waters, found the soil in fallowed fields was significantly drier, all of them said they’d recommend the program to neighbors.

As Waters chugged along at 4 miles an hour, dust and chaff clouding the windshield of his swather, he considered the possible future. Without water, the valley would turn into a dust bowl and his way of life would be lost, he said. “And if I’ve got to lose my way of life farming in this valley for people to keep living in Phoenix, where is that fair?”