In the southeast corner of Seattle’s Ballard neighborhood, there’s a five-by-five-block area within which you can find nine breweries. Pair this brewery-on-every-block notion with the fact that some of the oldest and biggest Seattle-area brewpubs, Redhook and Elysian, have closed large landmark spaces in the past two years, and you might think craft brewing has hit market saturation. In Portland, establishments such as Widmer and BridgePort — brands “this beer town was built on,” according to The Oregonian — have suffered a similar fate; Widmer closed its once-popular pub, while BridgePort is out of business entirely.

So have we finally hit the tipping point of craft beer out West? Beer writers dispute the idea.

“Every time a brewery closes, there are reasons why,” said Kendall Jones, who runs the Washington Beer Blog. “I don’t think we can point to anything about recent brewery closures that makes me think there’s a saturation issue.”

Although per-capita beer consumption continues to decline, down from 31 gallons per person a decade ago to less than 27, microbreweries and brewpubs continue to sprout. About 5,000 new breweries have opened since 2007, and Western cities are beer hotspots. San Diego, Denver, and Seattle all have 150 or more breweries — only Chicago has more. In Washington, 136 craft breweries were operating in 2011; by 2018, the total had swelled to 394.

Jones said breweries close not because too many producers are chasing too few customers. Elysian’s pub closure had more to do with new owner AB-InBev’s streamlining than its profitability, and the Redhook brewery shutdown, he argued, “has nothing to do with the state of craft beer.” Again, consolidation is the culprit — the Craft Brew Alliance, Redhook’s parent, centralized its brewing operations. (Representatives from both Redhook and Elysian declined to comment for this story.) For a better look at the health of the industry, Jones suggested a visit to any of the city’s hopping taprooms. “Go to Ballard on a Saturday afternoon,” he said.

“It’s a bit of a ‘rising tide floats all boats’ scenario,” said Brad Benson, the co-owner and head brewer of Stoup Brewing in the Seattle neighborhood. To him, the glut of breweries brings in more people to the taproom — which is the most profitable way of selling beer these days.

Jackie Dodd, the writer and cookbook author known as the Beeroness, said the free-for-all of anyone setting up a brewery and automatically being successful is over. During an earlier era, Dodd said, “you could compete with good branding and bad product.” Now: “The price of entry is good beer. There’s enough space if you have it.”

Take Portland’s BridgePort, which Dodd said was still producing the same malty India pale ale it had for ages: “[The kind of] beer people liked in 2010, ” she said. As the craft beer industry evolves, particularly toward juicy, hazy IPAs, breweries need to keep innovating, or risk being left behind.

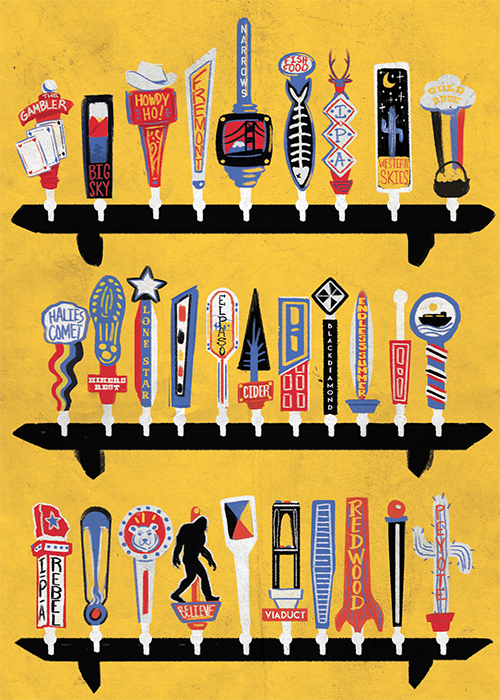

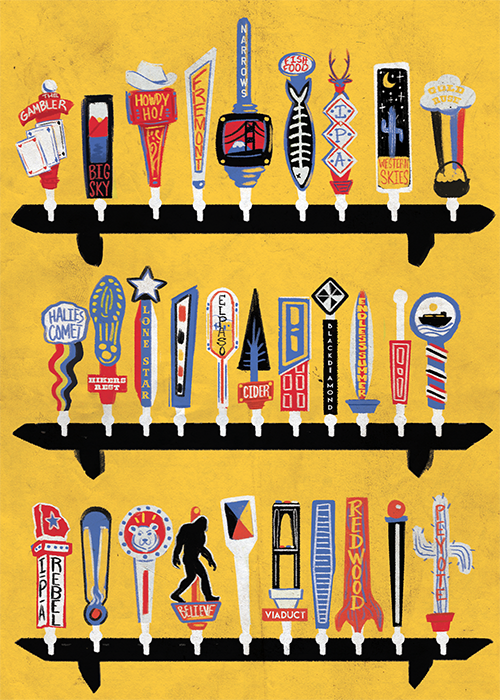

Big-money buyouts — think AB-InBev buying Elysian and Bend, Oregon-based 10 Barrel — might also be waning. Jones, of the Washington Beer Blog, noted that the one area of oversaturation in craft beer is on grocery store shelves. In pubs, having the latest and most interesting beers on rotating taps has become table stakes.

That’s especially challenging for middle-tier, regional brewers. When Redhook closed its Woodinville brewpub, the state’s largest, in 2017, The Seattle Times reported that domestic shipments of Redhook beers were down 37 percent, and the brewery was operating at 30 percent capacity. Midsize distributors like Craft Brew Alliance must compete not only with newer and more nimble craft brewers, but also with craft brands enjoying AB-InBev’s price advantages.

But when it comes to breweries that focus on selling their own beer out of their own taprooms, the market is still wide open, the experts say. “Ten years ago, a brewery taproom was a weird destination,” Jones said. “Today, it’s totally normal.”

According to a study commissioned by MillerCoors in 2017, 22 percent of Seattle’s overall bar traffic was in brewery taprooms; Portland (29 percent), San Diego (30 percent), and Denver (35 percent) saw even higher proportions of patrons headed to breweries. These Western cities are abnormal — the national average is just 9 percent.

A decade ago, Jones said, brewers would try to sell about 25 percent of their beer in their own taproom. Today, that number is closer to half and includes people drinking on site and spending money for off-premise enjoyment through growlers, crowlers, and cans.

That’s been Stoup’s approach. Benson has avoided grocery sales altogether, selling most of the beer through the taproom and kegs to bars around town. Seattle’s growth gives him more potential customers by the week, but quality still reigns supreme.

“People don’t give you a second chance like they did 15 years ago,” he said.

And all of those brewing neighbors? They don’t scare him. “Are people questioning if you have too many wood-fired pizza places?” he said. “There’s room for more if you’re doing it right.”