On a Tuesday morning in February, Brenda Nieblas, a small woman with a wide smile, pulled up a waiting list on her phone while standing in the kitchen of the Home of Hope and Peace, or HEPAC, a community center in Nogales, Sonora. The list showed about 900 names of people hoping to be granted asylum in the United States, around 200 of whom recently arrived in Nogales. Nieblas, HEPAC’s administrator, oversees this list of asylum-seekers staying in town while they wait to be processed by U.S. Customs and Border Protection at the DeConcini Port of Entry in the heart of Ambos Nogales, the colloquial term for the neighboring Arizona and Sonora cities that share a name. Most asylum-seekers on the list are from Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and the southern Mexican state of Guerrero. That day, there were also people from Venezuela, Brazil, and Eritrea.

“We welcome them [to Nogales] and give them an orientation of the asylum process. Then we drive them to one of the four main shelters in Nogales,” Nieblas explained (HEPAC provides shelter for women and children). Each day, CBP agents tell her how many people they can process; it’s usually about 10.

Nieblas has been in charge of this list since 2018. The number of asylum-seekers coming to Nogales hasn’t been this large, she said, since hundreds of Haitians arrived in 2016. President Donald Trump’s policies, especially the recent decision to send asylum-seekers back to Mexico while they await hearings, have put more strain on border towns, but large numbers of Central American asylum-seekers were on their way to Nogales regardless. From October to March, CBP’s Tucson sector, which includes the Ambos Nogales border crossings, apprehended more than 32,000 individuals.

Berta Ponce Mota, Brenda’s aunt, stood in the kitchen that morning, too. She and two other volunteers, Ana González and Elena Ramos, discussed what to cook that day. There’s a saying: The heart is in the kitchen, and that’s especially true in this kitchen. Here, the women cook daily meals for children growing up in some of the poorest barrios in Nogales, as well as for the asylum-seekers staying at the HEPAC shelter.

The community center sits atop a hill, surrounded by paved and unpaved roads, houses made of concrete blocks or wood, small bodegas, and abandoned cars. To the north, less than 15 minutes by car down the hill, stands the rusty, copper-colored border wall that divides Ambos Nogales.

The women decided on the day’s menu — burritos with eggs and refried beans — and got to work. Some of the ingredients came fresh from the garden behind the building, where they cultivate different herbs and vegetables. Eggs came from the chicken coop, and water from a tank with a purifier.

“My children would come here to eat when they were younger,” Ramos, one of the volunteers, said. That was a decade ago. “One day I stayed to help with the dishes. [Some volunteers] told me to join them in the kitchen … I love to cook. I came back the next day, and the next day. I didn’t ask if I was allowed to return, I just kept coming back.”

A few steps from the kitchen, a group of women played with their toddlers, all recently arrived asylum-seekers, waiting at HEPAC for their turn to be processed at the border. Four of them — three from Honduras and one from El Salvador — arrived a couple of weeks prior. Later in the afternoon, Nieblas would drive them to the port of entry.

The women, who will remain anonymous for their safety, journeyed for weeks, three of them with the recent caravans that numbered in the tens of thousands. They heard Nogales was calmer and safer than Tijuana, Baja California.

Three other women and their children came from Guerrero, one of the poorest and most dangerous states in the country. “There’s no work where we come from,” one of them said. “There’s the war between drug cartels. Guerrero has always had a history with violence, but people are dying every day right now. There are a lot of dead.” They fled in the middle of the night.

Those at HEPAC are helping the asylum-seekers reach the United States, but they would prefer these families remain in Nogales. Providing a fruitful livelihood for those in Nogales is the goal, but as a border city, that also means becoming a town that can offer opportunities for the immigrants and asylum-seekers that pass through daily. Nieblas and HEPAC’s volunteers hope to see Nogales grow into a destination — not just a waypoint for asylum-seekers dreaming of a better life across the border.

In addition to migrants on their way to the U.S., Nogales is filled with those recently removed from el norte. White buses and vans filled with asylum-seekers and undocumented immigrants deported from the U.S. are a daily presence here. In 2018, 25,376 Mexican nationals were deported to Nogales, according to Mexico’s Secretariat of the Interior. Deportees are released a few meters from the port of entry onto the traffic-heavy and deteriorated streets of downtown Nogales. Vans provided by the National Institute of Migration are parked nearby, waiting to transport many of the deportees to local shelters or the soup kitchen run by the Kino Border Initiative.

Railroad tracks divide downtown Nogales; residential neighborhoods lie to the east, and the tourist district to the west. Near the port of entry are dozens of pharmacies where U.S. citizens buy prescription drugs on the cheap. American tourists also buy Oaxacan crafts at the local market and photograph vibrant murals on abandoned buildings. Drivers honking nonstop and shouting street vendors constitute the downtown Nogales soundtrack.

For the deportados, the colorful houses that adorn Nogales’ hilly roads, the regional Mexican music that echoes through the streets, and the smell of carne asada tacos does not spark hope or excitement; rather, these details signify the end of a life in the U.S. they risked everything for. Some find work at one of the factories owned by U.S. companies. Others remain in Nogales only for a few days, until they find a new opportunity to cross the Sonoran Desert and return to their families across the border.

Migration has long been a part of life in Ambos Nogales, but only recently has militarized enforcement become such a defining element. Border Patrol agents and surveillance towers are omnipresent. Beginning in April 2018, some 1,600 National Guard members were deployed to the Arizona-Sonora border by the Trump administration, according to The Arizona Republic, in response to the multiple caravans of asylum-seekers from Central America making their way north. Concertina wire was recently installed on the Arizona side of the border fence, a place where families separated by deportation used to reunite for a quick embrace through the barrier slats.

The death of Nogales, Sonora, resident José Antonio Elena Rodríguez in 2012 weighs heavily on the Ambos Nogales community. Elena Rodríguez allegedly threw rocks at Border Patrol Agent Lonnie Swartz, who stood on U.S. soil 14 feet above the teen, while two men allegedly attempted to smuggle marijuana into Arizona. Swartz fired 16 shots at Elena Rodríguez, hitting him 10 times and killing the teen. Elena Rodríguez’ family denies that he was involved in drug smuggling, and says that he was merely walking home at the time of the shooting. Elena Rodríguez was unarmed. Swartz was found not guilty of murder and manslaughter in 2018.

Juanita Molina, executive director of the Tucson-based Border Action Network, says the case exemplifies the tension triggered by harsher immigration enforcement in Ambos Nogales. “Anybody who thinks about [the Elena Rodríguez] case, it brings chills up your spine,” she said.

Molina, whose own family immigrated from Chile to the U.S. in the 1970s to escape the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, supports social justice efforts in Ambos Nogales and elsewhere along the Arizona-Sonora border. “We are part of a region, whether you talk about it in terms of ecology, whether you talk about it from a social perspective — we are both sides of the line,” she said.

Molina brought up the famous Gloria Anzaldúa line:

1,950 mile-long open wound

Dividing a pueblo, a culture

Running down the length of my body

“And that’s exactly it” she said. “That’s why you see this profound response here in Arizona [to issues in Nogales, Sonora], because we are both.”

That’s why Molina supports the work of HEPAC. The group empowers residents of their own community, all while providing aid to asylum-seekers who have come to the border in an attempt to heal their own wounds.

Nieblas works at HEPAC alongside her mother, Juanita Ponce Mota, and her aunt, Berta; her father, Mario Nieblas, is HEPAC’s director. HEPAC’s roots are in serving the community of Nogales, but when the Trump administration began separating children from their parents at the border, they immediately began helping asylum-seekers.

Doing so was personal. Born in the central Mexican state of Jalisco, about 800 miles south of Sonora, sisters Juanita and Berta have firsthand experience with family separation. Berta is a reserved woman in her 60s; Juanita, 50, is petite and perky. Berta primarily volunteers in the kitchen, while Juanita oversees the shelter bedrooms, chores, and daily cooking.

“I met my father when I was 5 years old,” Juanita said. “‘Your dad is coming from el norte’ was what my mother would tell us. He’d come back for a month, and then leave again because of our economic situation.” She said their father, Felipe Ponce, never went to school. “But his world was very open. That was a tremendous motivation for us.”

Beginning in the 1950s, Felipe often trekked from Jalisco to the Western U.S. as an undocumented worker. At the time, the Bracero Program, a binational agreement between the U.S. and Mexico to bring Mexican workers for short-term labor, was in effect. The program lasted more than two decades, allowing nearly 5 million Mexican workers to be temporary legal residents of the U.S. However, there were nearly as many Mexican workers like Felipe who were turned away by the Bracero Program but came to the U.S. undocumented. “He’d cross on foot through the desert,” Juanita said.

In 1977, Felipe’s smuggler abandoned him in the desert, and he fell ill. “He had to find the highway to be apprehended by Border Patrol. He was very sick because of the cold,” Juanita said. Felipe was deported to Nogales, Sonora, and decided to stop crossing.

Juanita’s and Berta’s father found a city beginning to modernize. The Border Industrialization Program, enacted in 1965, allowed U.S. manufacturers to establish low-cost factories in Mexico. The factories, known as maquiladoras, largely employed immigrants from states farther south, such as Jalisco and Oaxaca, and contributed to Nogales’ population growth in the following years. In the 1960s, Nogales had about 40,000 residents; it’s now around 220,000. Maquiladoras remain the biggest employers in Nogales. Workers earn about 160 pesos, or $9, each day.

Upon arriving in Nogales, Felipe worked as a trash collector at the maquiladoras. He found shelter in a train car until he saved enough money to build a small, one-room home in what is now the barrio of Bella Vista. He then bought train tickets, one at a time, to bring his wife and 11 children from Jalisco. Juanita was 8 when the entire family reunited. Berta was much older, already married with a newborn baby, but she came, too.

“It had been four years since I last saw (my father),” Berta said. “There’s a saying that goes, Home is where you’re able to eat. So this is where we stayed. This is where we all found work.”

Bella Vista left much to be desired. “This neighborhood was completely abandoned. We didn’t have water, we didn’t have electricity, we didn’t have sewage, we didn’t have anything,” Juanita said. But as the community grew, residents came together to fight for change. Starting in the 1980s, they demanded the local government install electricity and water at many of the homes in Bella Vista. Over the years, most of the muddy roads have been paved, and public transportation now serves the neighborhood.

This community-driven ecosystem was the foundation for HEPAC. The official nonprofit was founded in 2010, but has existed informally for years. Nogales resident Esther Torres started what would become HEPAC as a small lunch program in her own kitchen in the late 1970s. Later, more neighbors joined Torres to make bagged lunches for at least 100 kids daily. Juanita was one of those children; later, her daughter, Brenda Nieblas, was too.

Over the years, the lunch program evolved into a broader suite of community services. HEPAC holds educational and empowerment workshops for youth, and hosts a biannual kids’ camp. Visitors can take guitar, yoga, and art classes; adult tutoring and workshops for trauma and conflict resolution are also offered. Kids who can’t afford them receive clothes, toys, school supplies, and backpacks.

Juanita remembers her father telling her that he wished he could have found other options in a border town sooner, so that he didn’t feel his only path to provide for his children was to head to the U.S. She feels the same: Juanita’s family lived in Arizona for three years. Mario had a work visa, and wanted their children to experience life on the other side of the border and to learn English.

“I didn’t like it. Life there is expensive and lonely,” Juanita said. “I missed the crowing of the roosters, the street dogs, the man who sells oranges … I missed all of that.”

They returned to Sonora even more motivated to invest in their own community. “What are life’s priorities? Your children, your family, and then your community,” Juanita said. “If you get ahead and are able to help your community, everyone gets ahead.”

While HEPAC supports those in town waiting their turn to cross the border, this family maintains that Nogales can be a destination of hope, too.

“We close off to the idea that el norte is the solution to all of our ills,” Juanita said, referring to fellow Mexicans. “I believe that there are other options for us. If you come to the border, there are options to survive. There are work opportunities here that don’t exist in [southern Mexico], so that maybe there’s no need to cross this desert.”

Many of the youth in Nogales have grand ideas of what it’s like to migrate across the border. They hear that if they become coyotes, the smugglers who guide people crossing into the U.S., then they’ll make loads of money. While drug cartel violence has decreased in Nogales, Sonora in recent years, some of the vulnerabilities of living in a border town are still very much present. And the current tensions surrounding immigration and the U.S.-Mexico border introduce even more complications.

“We have great role models here,” Juanita said. She points to Mario, who struggled — for a time, he was homeless — but remained in Nogales. “He helped another boy from this neighborhood, Cristian. Everyone here [at HEPAC] knows Cristian. His mom was a sex worker and his sisters had drug addictions. This boy graduated from college [in Nogales, Sonora] last year as an engineer. We use him as an example all the time. Did he have to go to the U.S. to make a living? No.”

Today, more Mexicans are staying in Mexico. According to the Migration Policy Institute, the number of immigrants from Mexico living in the U.S. without documents declined by more than 1 million between 2007 and 2016, a decrease due in part to Mexico’s improved economy. Juanita and the women’s cooperative of HEPAC believe that if people are provided with education, dignified jobs, and other life necessities, they will stay.

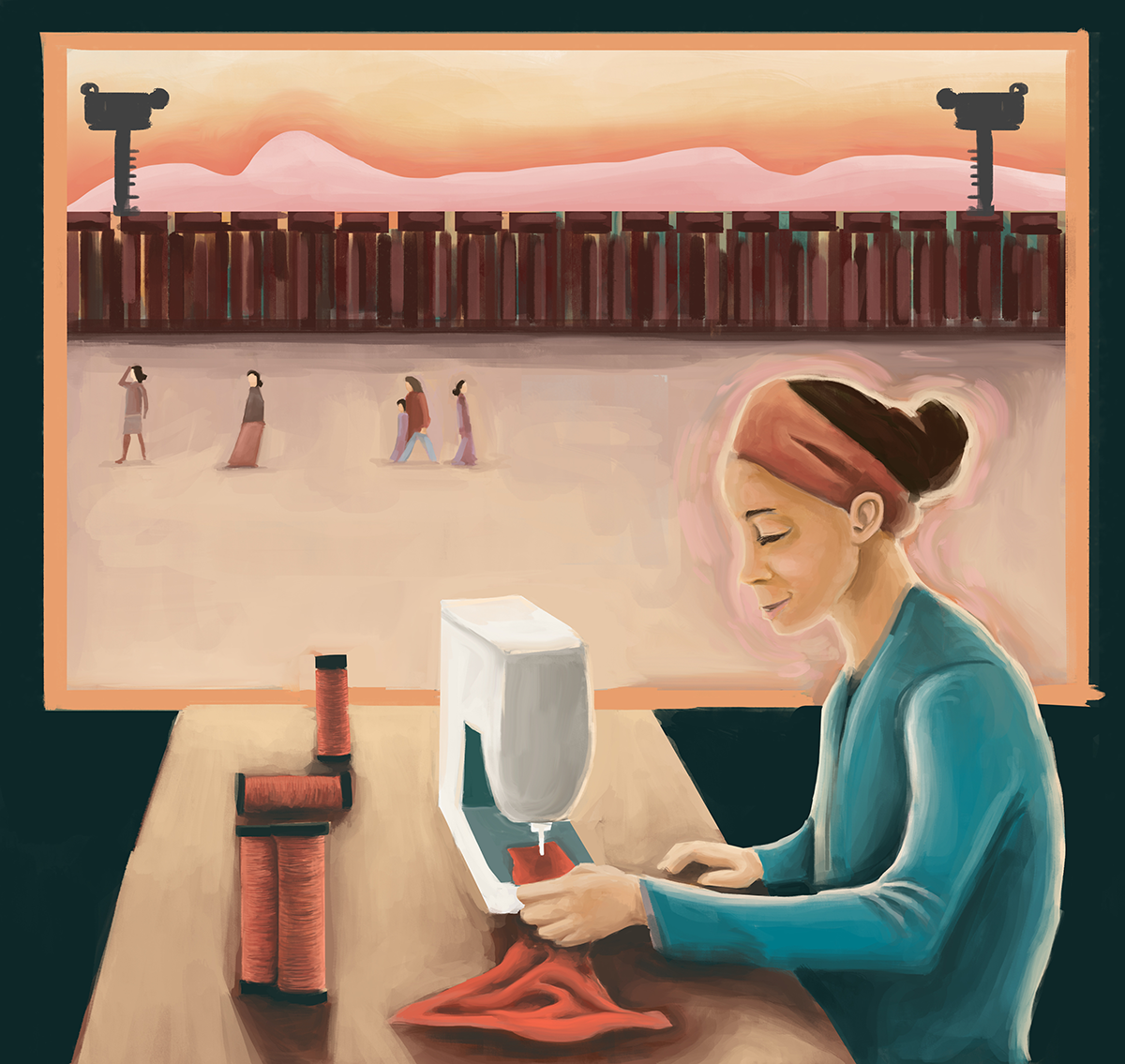

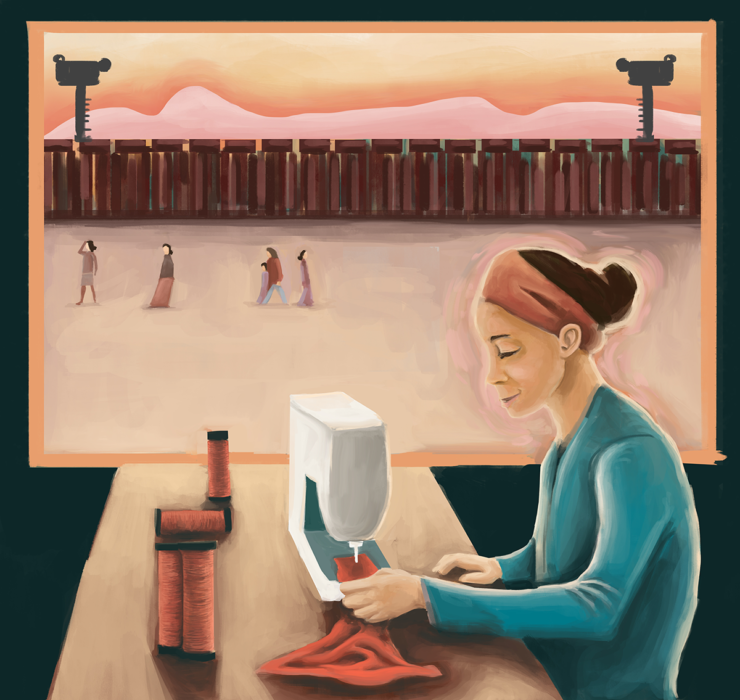

To be sure, HEPAC has been able to expand its community-focused mission in recent years thanks to support from their neighbors across the border. Many of the supplies HEPAC receives for the children it serves are donated from churches and organizations in Tucson, Arizona. Their programs are funded with donations from across the border. The crafts women make during daily sewing time are sold in the U.S. thanks to a collaboration called Mujeres Unidas.

Michelle Perrin first heard about HEPAC in 2013. Perrin is a member of the United Church of Christ, and her Tucson congregation is heavily involved in immigration issues. She and other members of her church began to brainstorm ways in which they could help women and children across the border, and they started to work with HEPAC’s sister organization, Tucson-based Friends of HEPAC, to aid the group in Nogales. At one point, the group knitted winter sweaters for kids in Nogales. Perrin and others decided to teach the women of HEPAC to knit and crochet themselves, so that they could make sweaters and other items for the children. She started driving to Nogales every Monday, and did so for two years. “We had this [sewing] group,” she said. “We created wonderful friendships.”

And thus Mujeres Unidas, the women’s cooperative arm of HEPAC, was created. With donated sewing machines, the women from both sides of the border got to work. They made necklaces, aprons, and kitchen sponges. With revenue from their crafts, HEPAC was able to buy new kitchen equipment. Today, Perrin drives to Nogales, Sonora a couple of times a month to drop off donated recycled cloth and other materials. She also picks up the finished products that are later sold in Arizona. Their craftwork partially funds HEPAC’s operations and provides some nominal pay for the volunteers. Every product comes with a tag that describes the programs at HEPAC and the role of Mujeres Unidas.

Nieblas said that empowering the community of Nogales, Sonora is beneficial for the future of both Mexico and the U.S. “We believe that to make this better … it’s a binational effort that both [countries] have to support. This center focuses on children. Why? Because they are the next generation. Everything we do here is to support them, so that in the future they don’t [feel it’s a necessity] to migrate.”

For Perrin’s part, on the other side of the border, she supports the women trying to make a better life for the future generations in Nogales, Sonora, but says empowering the women themselves to make their own lives better is part of what drives the work of Mujeres Unidas. “There is so much love involved in all of what we’ve been a part of here,” she said. “They are wonderful, happy women. But life is tough [in Nogales].”

On a Thursday afternoon in February, Juanita and Berta sat in front of their sewing machines. The cloth quickly flowed underneath their fingers. Their needles embroidered the shapes of cacti and other distinctive images of the Southwestern and Sonoran desert landscapes. They were making aprons and various crafts that would later be sold in Phoenix, Tucson, Tubac and other cities in southern Arizona.

The small windows in the sewing room overlook most of Nogales, Sonora: Its hills and mountains in their splendor, a sea of colorful homes and the roofs of the maquiladoras. Thick gray clouds covered the sun. Juanita and Berta had been there since 9 a.m. The two sisters would continue working until 6 p.m. Maybe later.

Just as the work done by HEPAC is about more than lunches for children and beds for asylum-seekers, the work of Mujeres Unidas supplies more than funds for the women and their programs. They have created a sisterhood with a purpose. “Sometimes we come [to HEPAC] with our self esteem on the ground,” Berta said. “But we’ll talk, we’ll sing … [we’ll] work, and our self esteem goes right up.

“When my husband died [a few years ago], I fell into a very deep depression,” she continued. “[These women] are my family. We miss each other when we don’t see each other. It was this work … with the children that got me out. I have kept going with a lot of pride and satisfaction. I’ll keep going until God lets me.”