The 58 stories posted in just three days detailed punishment for wearing shorts, being privy to friends drinking or doing drugs, and being raped. On the Instagram account @byuihonorcodestories, anonymous students, former and current, of Brigham Young University-Idaho shared stories of their experiences with the campus Honor Code Office. While the content differed, there were commonalities: these were students who clearly felt angry, frustrated, and confused by the workings of the campus office.

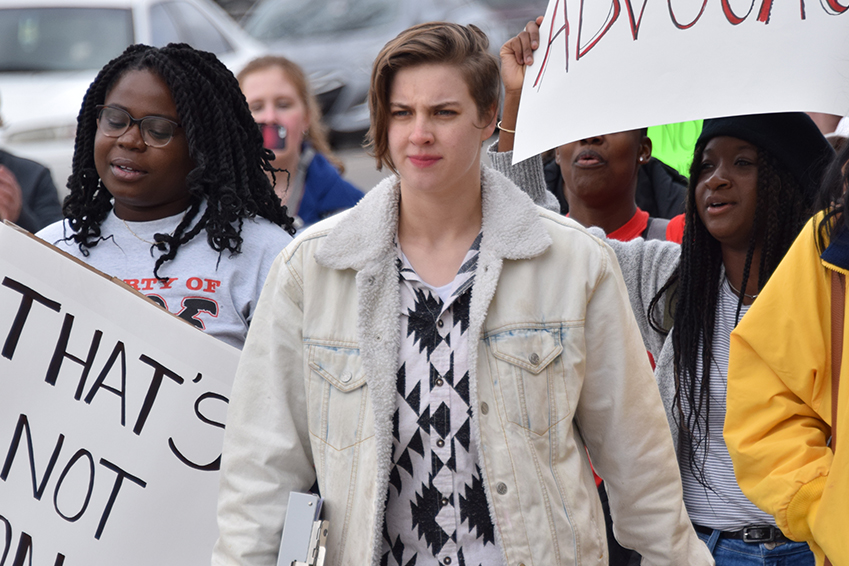

On the afternoon of Wednesday, April 10 — less than a week after the account was created — the posts materialized in the form of signs held by approximately 150 students marching in protest on the BYU-Idaho campus in Rexburg.

It’s not uncommon for universities to create rules and guidelines around student conduct, usually related to cheating and plagiarism. But at BYU institutions, which are owned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, students must agree to a list of behavioral and physical directives, as well. These include upholding the beliefs of the church; following a curfew (midnight from Saturday to Thursday, 1:30 a.m. on Fridays); dressing appropriately (skirts and shorts knee-length or longer, no more than one pair of earrings, no beards or long sideburns); and abstaining from drugs, alcohol, sex, tobacco, coffee, and tea.

Of the 20,000 students on campus, more than 98 percent are church members. Those at the rally were not protesting the code itself, but asking for a change to the way Honor Code violations are enforced. “An Honor Code [implies that] one would come to it with one’s own repentance process,” Garrett Matthews, 19, said. But the way the BYU-Idaho Honor Code Office works, he said, “encourages students to turn one another in … and conversations between students and faith leaders are not confidential.”

Like all members of the Mormon church, students are encouraged to confess any self-proclaimed wrongdoing to their assigned bishop, but at school any violation of the Honor Code can be taken up by an employee of the Honor Code Office, a member of the church who holds no appointed ecclesiastical ties.

“I’m angry at the way things have been treated. Especially because I don’t think it reflects the church I belong to,” said Melanie Urmston, 21. “Our church is about repentance, it’s about forgiveness.”

Urmston said the way the Honor Code Office incites fear of suspension or expulsion in students — even if they are victims of assault or rape on campus — is not in line with this teaching. She knows people who have gone in to the Honor Code Office to report something, and ended up being punished themselves “because they broke curfew, or they were someplace they weren’t supposed to be,” she said.

BYU-Idaho officials did not respond to requests for comment.

Many at the protest referred to the trauma the Honor Code Office can cause for victims of sexual assault on campus. Though many colleges and universities around the country struggle to deal with assault victims and accusations appropriately, BYU’s Honor Code, which includes a promise of chastity, adds an extra layer of complexity.

“In a lot of cases of rape here, the person who has been raped has also been expelled [due to a breach of the Honor Code],” said Remi Boland, 20. “The person who was raped should be comforted and helped.”

Furthermore, Boland said schools kicking out students who have violated the code may be harming the Latter-day Saint church itself. “In the church, we’re taught to be loving and treat people as Christ had, and if someone has done something wrong, to help them repent. I think if we’re not doing that, then that is pushing people away from the church.”

For protest organizer Grey Woodhouse, 23, that was the case. Woodhouse was suspended for one semester for knowing about a party and not reporting it. Her friends who attended the party were suspended for one year, after which none returned to BYU-Idaho. Last semester, she was suspended again, and eventually expelled, for violations the office discovered she had committed as much as a year prior, including having one sip of beer, she said.

“I felt the fear the Honor Code Office inflicts on its students,” she said, “but they pushed me past my breaking point, and I’m no longer scared of them.”

While Woodhouse admits she was already drifting from Mormonism, her experience at BYU-I ultimately ended her confidence in the faith. “The school … pushed me so far that I want absolutely nothing to do with the church now.”

Some students are hopeful the school will change. Leanne Larson, 21, organized the protest alongside Woodhouse. She was suspended for two semesters for an infraction she’d prefer not to reveal. She said that though she broke the Honor Code and repented with her bishop, “the Honor Code Office decided it didn’t count.” Larson has chosen to continue at BYU-I. “I was wronged by the Honor [Code] Office, but luckily my faith in the church was too strong for me to go home, and I’m going to be a student again.”

The rallying students began at the north end of the school and walked south along the sidewalks bordering campus. Halfway through, the group stopped on a street corner as Woodhouse and Larson delivered letters of complaint to the Honor Code Office. There, they were directed to the Dean of Students’ office. The movement’s organizers have yet to hear back from the school or its administration.

In the meantime, protest is spreading throughout the BYU universe. The BYU-I Instagram account had followed in the footsteps of a similar account, @honorcodestories, launched in January by students at the flagship BYU campus in Provo, Utah. Two days after the rally in Rexburg, hundreds of students held a similar protest in Provo.