By the numbers, voters in sparsely populated Western states have more say in choosing the president. Nevada has one Electoral College vote for every 506,000 residents; New York, on the other hand, has one per 674,000. But for the individual voter, that advantage kicks in only if your choice matches your state’s — a Wyoming Democrat’s presidential vote, for instance, does little more than pad their candidate’s ego.

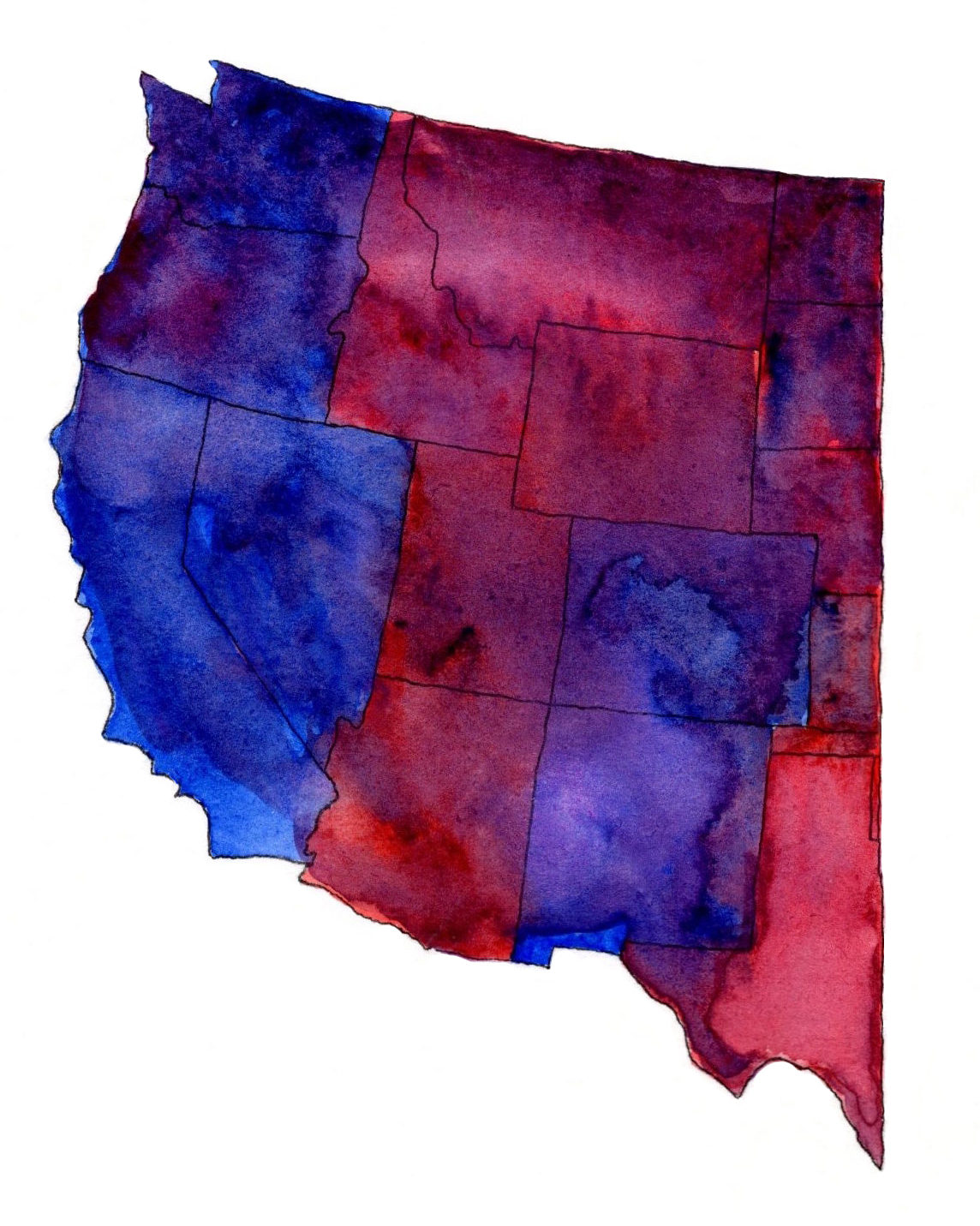

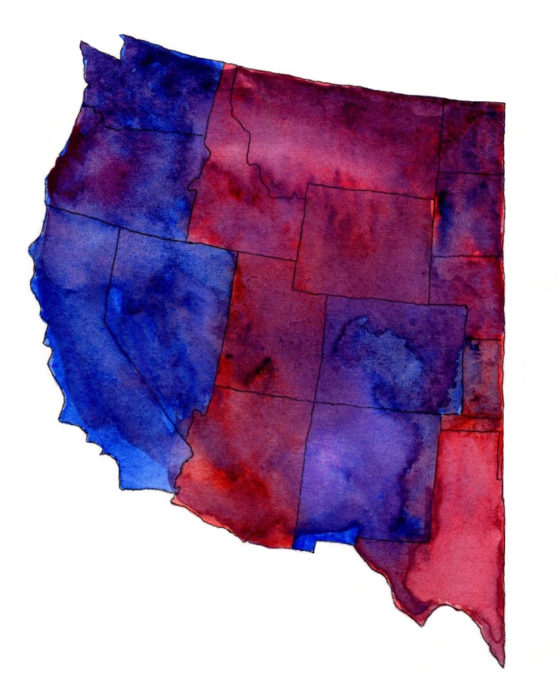

But, at a time when two of the last three presidents won even though more Americans voted for their opponent, legislators from several Western states are working to remake the presidential selection process. This session, Colorado and New Mexico passed legislation to join the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, a workaround to the Electoral College that awards a state’s presidential electoral votes to the national popular vote winner. Legislators in two other Western states, Oregon and Nevada, are considering legislation that would do the same. Collectively, their efforts illustrate a rising tide of progressive sentiment in the Western political landscape. California and Washington have already signed on.

“We have 514,000 elected officials in the United States of America, and each and every one of them is elected by the popular vote of the people, except for one. And that is the president of the United States,” Assemblyman Tyrone Thompson, lead sponsor of Nevada’s popular-vote compact legislation, said during a legislative hearing. Nevada’s measure passed the Assembly on April 16.

Doing away with the Electoral College would require a constitutional amendment, but by joining the compact, states pledge their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote. The agreement only has teeth if states accounting for a majority of electoral votes (270 out of 538) have joined, thus guaranteeing that the presidential candidate who wins the popular vote also wins the Electoral College. Since Maryland legislators kicked off the movement in 2007, states with 189 electoral votes have signed on.

Legislation to pass the compact indicates a change in the Western political landscape. Increasingly progressive electorates in these states have pushed this issue on to the political agenda. Democrats in Nevada, New Mexico, and Colorado gained control over both legislative houses and the governor’s office in 2018, and Oregon’s politicians face an increasingly progressive base impatient for change. Together, Oregon and Nevada would add 13 more electoral votes to the compact.

Though electing presidents via the national popular vote was once overwhelmingly and bipartisanly popular — Gallup polls from the ’70s and ’80s show that about two-thirds of Americans supported it — recent efforts to enact the compact have been pushed by Democrats. The four Western states considering legislation this session are trending left in national elections — a major, and recent, shift. Fifteen years ago, three of the four states cast their electoral votes for George W. Bush, and all four were considered swing states; Colorado and Nevada still are, though some prominent political analysts are reconsidering that classification for increasingly liberal Colorado.

According to Seth Masket, a professor of political science at the University of Denver, swing states have had little reason to consider the compact because the Electoral College incentivizes presidential candidates to focus on the handful of states that might vote one way or the other.

“Campaigns mostly spend their time and effort in states that are close,” Masket said. “And they largely ignore most small rural states and even some large electoral prizes like California, Texas, and New York, simply because they’re not competitive.”

Indeed, in 2016, after Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton clinched their respective nominations, their visits to the West centered on Colorado, Nevada, and Arizona (a traditionally red state that’s trending blue).

Diluting its swing-state clout has some Nevada lawmakers nervous about joining the compact — even progressive ones. Majority Floor Leader Teresa Benitez-Thompson, one of the state’s most powerful Democrats, is leery of lessening Nevada’s importance in presidential elections.

“We in Nevada have worked so hard to make sure our voice is bigger than we are in the presidential caucus,” she said during a March event hosted by the Reno Gazette-Journal. “I just don’t want Nevada to lose a very unique position. We have a pretty big influence, and I want to protect that.” Benitez-Thompson voted against the compact measure.

But sponsor Tyrone Thompson portrays the legislation as a matter of fairness. “I want to be clear that this bill is not about partisanship, but a need for our voters — current and future — to feel and know that their vote matters in arguably the most important vote they will cast every four years,” he said.

There’s less consternation in Oregon. Under political pressure, Senate President Peter Courtney, who in the past stymied compact legislation, allowed a vote this year. Courtney still voted against the measure, but supporters nevertheless had the votes to pass it in the Senate. The legislation now sits in the Oregon House, where versions of it have passed multiple times since 2009.

Passage in a state as swingy as Nevada might portend future success for the compact on a national scale. “The states that have passed it have had a fairly strong Democratic lean,” Masket said. “So if we’re seeing serious swing states pass it, that suggests that this thing does have a shot at getting enough votes to be functionally ratified within the next few years, or the next decade.”

Even after running the legislative gauntlet, however, questions surround the compact’s legality. Proponents maintain that the Constitution allows states to delegate their electoral votes however they wish, but opponents argue that agreements between states are illegal unless approved by Congress. If the compact reaches the 270-vote threshold, litigation in federal courts is sure to follow.

The compact as a whole is unlikely to be enacted before the 2020 presidential election, but it’s still worth watching its progress in Oregon and Nevada. The political landscape of the West is changing, and this legislation could chip away at the notion of “red states” and “blue states” as we know them.