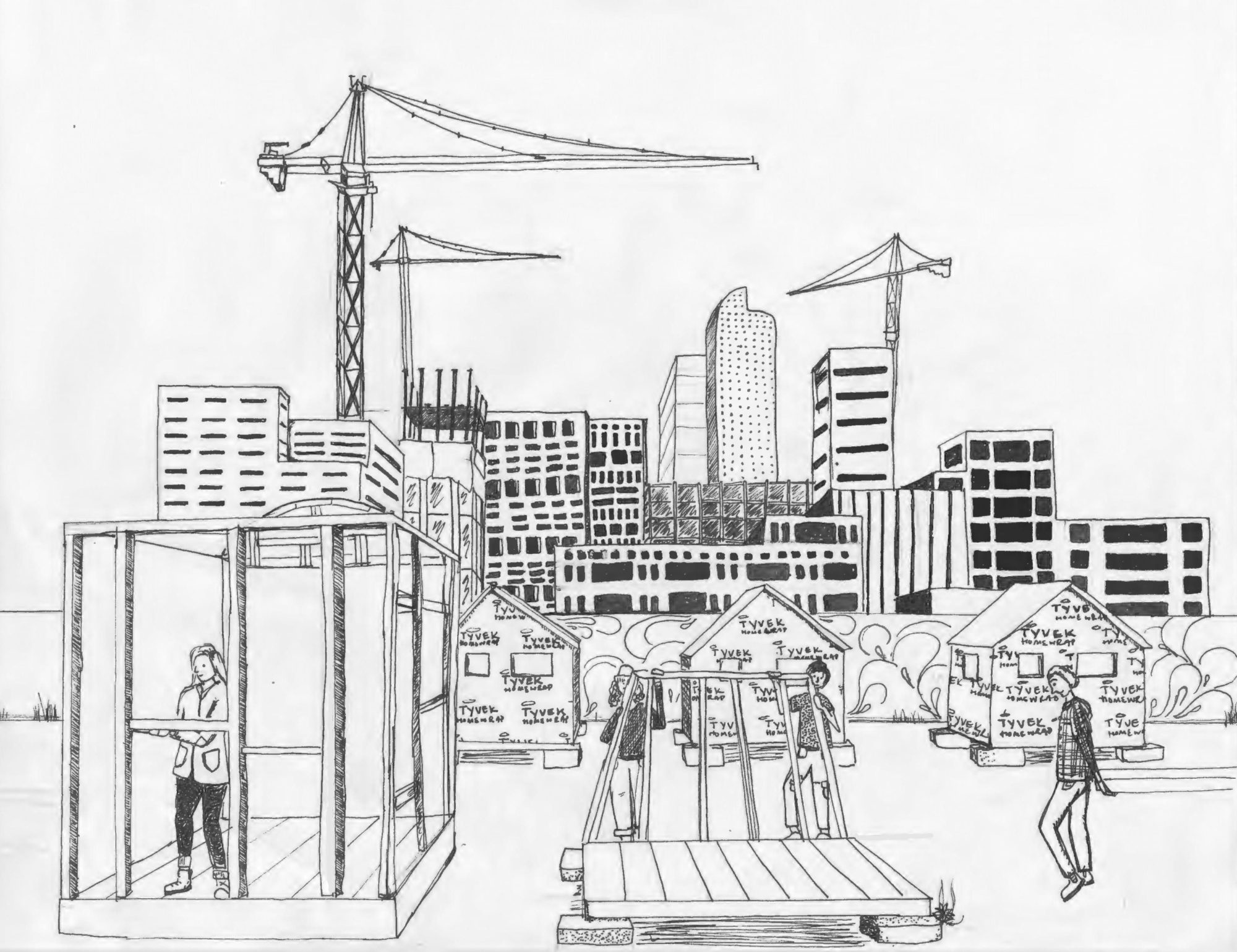

On a dreary April morning, 11 diminutive charcoal structures near downtown Denver seemed to blend into the sky. The tiny homes — small windows, white doors, abbreviated wood porches — sit on an oddly shaped gravel lot sandwiched between a microbrewery and a light-rail station. The entrance to Beloved Community Village, as it’s known, has a blue welcome sign and a Little Free Library kiosk; the fence that encircles it is decorated with colorful plastic strips, adding some brightness to an otherwise monotone scene.

But construction trailers and constant hammering signal an end to the monotony. Soon, a 66-unit affordable housing complex will replace the 8-by-10 structures. These apartments are designated for low-income renters, but they won’t be move-in ready until next spring, which means Beloved’s tenants, all of whom previously experienced chronic homelessness, need to relocate.

The entire village is slated to move about a mile northwest to a vacant, city-owned lot in the Globeville neighborhood. At least, that’s the hope. The Denver City Council still has to approve the proposed move; a vote is expected on April 29. Advocates are confident the decision will be in their favor, but if it doesn’t pass, Beloved’s 12 residents will be back on the streets.

That would be a critical setback for Freddie Martin. The 45-year-old expects to graduate from Metropolitan State University of Denver next month with dual bachelor’s degrees in history and anthropology. Living at Beloved for the past 13 months has “made school possible,” he said. “I can’t imagine being able to make it to classes if I was sleeping behind dumpsters. As a student, that’s absolutely crippling — having no certainty about your living situation or where your next meal is going to come from. This place has made my education and its completion possible.”

The uncertainty Martin and his neighbors face illustrates the limitations of tiny-home villages, one of the more in-vogue homelessness remedies. Explosive growth — the Denver metro area has added about 133 residents per day over the past eight years — rising rents, stagnating wages, and lack of political will at the local and federal levels has created a housing crisis in Denver and other Western cities.

One response has been the proliferation of tiny homes. They’re not the luxury, off-the-grid lodgings seen on HGTV, though. These communities of micro houses — some just repurposed prefab sheds — are designed to get those experiencing homelessness off the streets and into their own residences.

Proponents say tiny homes are a cost-effective, quick, and inclusive way to help close the housing gap. Micro houses can serve populations left out of the shelter system, such as couples who want to stay together or individuals with pets, and offer more privacy and security than a shelter bed. “We have to prioritize low-income housing, and that is the ultimate solution. But in the meantime, we don’t want people dying on the streets,” said Sharon Lee, executive director of the nonprofit Low Income Housing Institute in Seattle, which manages more than 350 micro houses that serve about 1,000 people annually.

Lee has seen positive results: 34 percent of people who left LIHI’s tiny homes in 2018 moved into long-term housing, compared with 21 percent of people who left Seattle’s enhanced-shelter projects, according to city statistics.

Success, though, is in the eye of the beholder. Some advocates express concern about the living conditions in tiny-home communities and the further marginalization and stigmatization of individuals experiencing homelessness. They also point out that low-density properties housing 10, 20, 30 individuals may be getting in the way of building much larger quantities of affordable units.

“The range that I’ve seen across the country is really, really variable. In many places, there continue to be these substandard conditions,” said Barbara Poppe, a national expert on homelessness and former executive director of the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness. “They need to have intentionally provided housing placement services as part of the model, and that’s not happening everywhere. It’s really all about the details and the local community.”

Characteristics of tiny-home villages vary between states and even within cities. Some, Beloved included, are self-governed. Some, like Quixote Village in Olympia, Washington, are designed as permanent supportive housing, complete with a full-time case manager; others offer limited services, if any. Electricity and toilets are inside some units; residents elsewhere use port-a-potties. Some require tenants to pay rent; some are free. Financial support comes from nonprofits, churches, the cities or counties where they’re based — and sometimes a combo of the above.

It’s not surprising that western cities are taking the lead on these efforts. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s 2018 report on homelessness showed that, among the 10 states with the most homeless individuals, nearly half — California, Washington, Oregon, and Colorado — are in the West; California, Oregon, and Nevada have the highest rates of unsheltered homelessness in the country. What’s more, according to a March report by the National Low Income Housing Coalition, there are eight states with fewer than 30 affordable and available homes for every 100 extremely low-income renter households. Six of them are located in the West.

Colorado is one such state. On any given night in Denver County, nearly 3,500 people are experiencing homelessness, more than 600 of them unsheltered. Beloved Community Village began making a small dent in those figures when its overarching nonprofit, Colorado Village Collaborative, opened the site in mid-2017.

Since then, Beloved has sat, temporarily, on Urban Land Conservancy property that was slated for redevelopment into affordable housing. The conservancy, which leased the land to CVC for $1 per month, has provided a number of extensions to the nonprofit as it works to find a new destination for Beloved.

It’s not an unusual problem. Tiny-home villages are often located on unused city property — acreage that can be pulled out from under residents at a moment’s notice. “Being able to expand this model is realistic,” said Tanya Salih, co-director of CVC. “It’s just a matter of finding the land.”

For now, she hopes that new land is vacant city property in Globeville. Despite vocal opposition from some neighborhood residents, Denver City Council’s Finance & Governance Committee voted last week to approve the lease — $10 for one year, renewable for up to two years, with a go-ahead for nine additional units and a community center — and it heads to the full Council for final approval next week.

“I do believe the model has promise,” said Denver Councilwoman Robin Kniech, who voted to advance Beloved’s new lease from committee. “I am a huge fan of housing first … but I can’t build housing fast enough. I have to be practical; I can’t ignore the need for other interim solutions.”

Early results indicate Beloved has indeed benefited its residents. An evaluation by the University of Denver’s Burnes Center on Poverty and Homelessness found that residents were more stable after nine months, and almost 90 percent of neighbors surveyed said the tiny-home village had no impact or a positive impact on the area. Salih points to two other markers worth celebrating: Five former residents have transitioned to full-time housing, and every current resident is either employed or in school, with one on disability. But, with the City Council vote looming, the volatility of some of these communities is coming to the fore.

“I worry a little about tiny homes starting up and being shut down and starting up and being shut down,” said Cathy Alderman, vice president of communications and public policy at the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless. “This, for a population of people who have had so many doors closed on them anyway.”